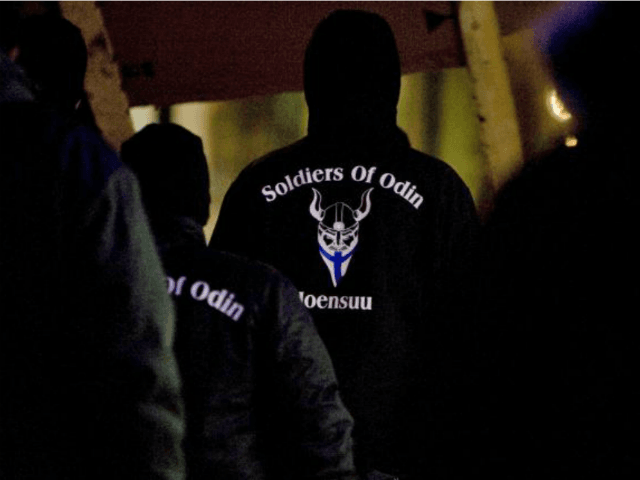

HELSINKI, Finland (Reuters) – Wearing black jackets adorned with a symbol of a Viking and the Finnish flag, the “Soldiers of Odin” have surfaced as self-proclaimed patriots patrolling the streets to protect native Finns from immigrants, worrying the government and police.

On the northern fringes of Europe, Finland has little history of welcoming large numbers of refugees, unlike neighbouring Sweden. But as with other European countries, it is now struggling with a huge increase in asylum seekers and the authorities are wary of any anti-immigrant vigilantism.

A group of young men founded Soldiers of Odin, named after a Norse god, late last year in the northern town of Kemi. This lies near the border community of Tornio, which has become an entry point for migrants arriving from Sweden.

Since then the group has expanded to other towns, with members stating they want to serve as eyes and ears for the police who they say are struggling to fulfil their duties.

Members blame “Islamist intruders” for what they believe is an increase in crime and they have carried placards at demonstrations with slogans such as “Migrants not welcome”.

While most Finns disapprove of the group, its growth signals disquiet in a country strained by the cost of receiving the asylum seekers while mired in a three-year-old recession that has forced state spending and welfare cuts.

Finnish police have also reported harassment of women by “men with a foreign background” at New Year celebrations in Helsinki, as well as at some public events last autumn.

This followed complaints of hundreds of sexual assaults on women in Cologne and other German cities – with investigations focused on illegal migrants and asylum seekers – and allegations that Swedish police covered up accusations of similar assaults by mostly migrant youths in Stockholm.

Police files show reported cases of sexual harassment in Finland almost doubled to 147 in the last four months of 2015 from 75 in the same period a year earlier. The figures give no ethnic breakdown of the alleged perpetrators.

NO PLACE FOR VIGILANTES

The government has made clear there can be no place for vigilantes. “As a matter of principle, police are responsible for law and order in the country,” Prime Minister Juha Sipila told public broadcaster YLE on Tuesday, responding to concerns about the group. “Civilian patrols cannot assume the authority of the police.”

Finland received about 32,000 asylum seekers last year, a leap from 3,600 in 2014. Yet it has a relatively small immigrant community, with only around 6 percent of the population foreign-born in 2014 compared with a European Union average of 10 percent.

In Kemi, the Soldiers of Odin patrol the streets daily despite the temperatures sinking to -30 Celsius (-22 Fahrenheit). The group has stated it operates in 23 towns, but police says the network operates in five. Its Facebook page has 7,600 “likes”.

“In our opinion, Islamist intruders cause insecurity and increase crime,” the group says on its website. One self-proclaimed member, aiming to recruit new members in the eastern town of Joensuu, said on Facebook the group is “a patriotic organisation that fights for a white Finland”.

In the eastern German city of Leipzig, more than 200 masked right-wing supporters, carrying placards with racist overtones, went on a rampage this week.

Last October, a masked swordsman in Sweden killed two people with immigrant backgrounds in a school attack that fuelled fears that the refugee influx is polarising public opinion.

In Finland, no clashes have been reported between the Soldiers of Odin patrols and immigrants but police said they are keeping a close eye on the group. The Security Intelligence Service has said “some patrol groups” seem to have links to extremist movements.

LET THE POLICE DO THEIR JOB

Police acknowledge patrolling alone is not a crime. “As long as the patrols only report possible incidents to police, they have the right to do so,” said Kemi police Chief Inspector Eero Vanska. However, he added: “They should let the police do their job.”

Some Soldiers of Odin members play down the group’s motives, saying it aims to help people regardless of their skin colour. The group has closed its website following reports on some members’ criminal background. Members contacted by Reuters declined to comment.

But one of the group’s founders in Kemi, Mika Ranta, made clear immigration was the focus.

“We woke up to a situation where different cultures met. It caused fear and concern in the community,” he told a local newspaper in October. “The biggest issue was when we learned from Facebook that new asylum seekers were hanging around primary schools, taking pictures of young girls.”

Vanska said some asylum seekers had been seen near schools with phones. But he added that these reports could be simple misunderstandings and there was no concrete evidence to support the accusations.

The coalition government – which includes The Finns, an anti-immigration party – has criticised the patrols.

“These kinds of patrol clearly have anti-immigration and racist attributes and their action does not improve security,” interior minister Petteri Orpo told Reuters. “Now the police must commit its scarce resources to (monitoring) their action.”

But the government faces pressure to clamp down more on asylum seekers. Support for The Finns party, which joined the coalition in May, has plummeted partly because voters are frustrated with the government’s handling of migrants.

The government has tightened immigration policies, requiring working-age asylum seekers to do some unpaid jobs and acknowledge a “national curriculum” on Finnish culture and society.

The patrols have also prompted a counter-movement, with Facebook communities hoping to avert confrontations on the streets. One such is the Sisters of Kyllikki, named after a character in the national epic poem Kalevala.

“Our aim is to help people and to build up dialogue with all Finns as well as with immigrants,” said Niina Ruuska, a founder of the group which has about 1,500 Facebook members.

(By Jussi Rosendahl amd Tuomas Forselle; Editing by Alistair Scrutton and David Stamp)