Owen Jones and Russell Brand often rail against ‘neo-liberalism’. According to them, the last three decades have seen an unprecedented experiment in ‘free market economics’ – characterised by a radical slashing of state spending, an erosion of the welfare state, privatisation, outsourcing and deregulation.

OK, they would say that wouldn’t they? It’s certainly true that in this period global trade became freer and capital more mobile, while we removed controls on prices and incomes, privatised the old nationalised industries, reduced the power of trade unions and allowed resources to flow freely into and out of the UK. Most of these reforms occurred under Margaret Thatcher. There has also been a retreat from the crude hydraulic, neo-Keynesianism expressed by 79 economists in The Guardian last week. On a global level, liberalisation in the form of expanded free trade has ensured that we have had the fastest reduction in world poverty in the history of the planet.

But in truth, these policy changes have to some degree been minor aberrations from a long-term trend of greater government control – of politicians and civil servants centralising power, and taking decisions away from individuals, families, civil society institutions and local government. Far from a ‘neoliberal’ free-market utopia, the UK state is in many was as intrusive as ever.

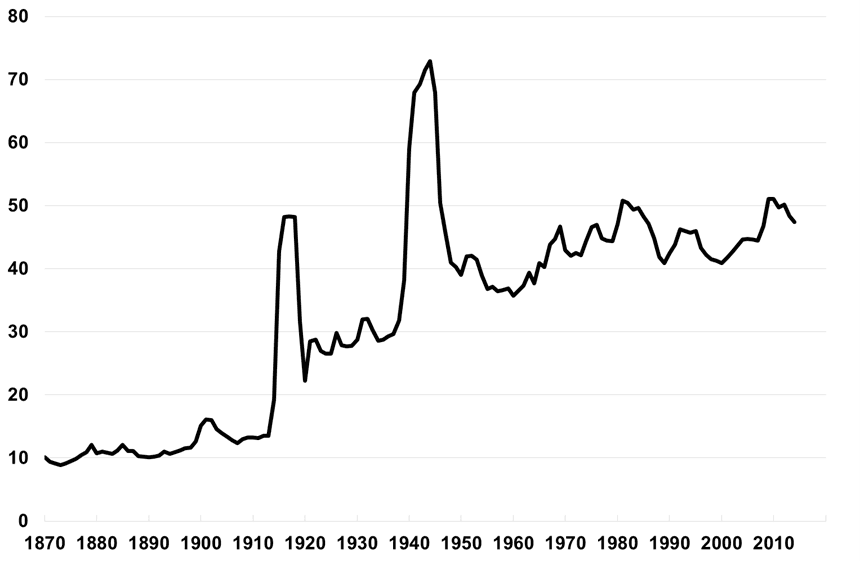

1. THE STATE IS ALMOST AS BIG AS IT’S EVER BEEN, IN PEACETIME

Government spending increased from around 10 per cent of GDP at the beginning of the 20th century to 47 per cent in 2014. It jumped significantly during the two world wars, never falling back to pre-war levels. It also saw a significant expansion in the 1950s-1970s.

Figure 1: General government expenditure as a proportion of GDP at factor cost

Despite claims we live in a neo-liberal age, state spending as a proportion of national income was actually higher in 2014 than in any year between 1947 and 1979 – the supposed big-government era before Mrs Thatcher’s administrations were said to have broken the post-war consensus.

2. THE WELFARE STATE GROWS AND GROWS

The scope of government has grown massively in the last century or so too. As AJP Taylor noted, in 1900, most law abiding Englishmen would only encounter the state through the Post Office or by passing a policeman on the street. Then, state expenditure on welfare, health and education was just 1.6 per cent of the UK’s national income. These services were overwhelmingly provided by civil society institutions, such as friendly societies.

Now, expenditure on welfare, health and education make up 63.5 per cent of overall state expenditure – equivalent to 29 per cent of national income. The coalition government actually expanded the welfare state yet further into new fields with more state funding for pensions, childcare and the provision of ‘free’ school meals. Spending on health, education and social protection rose in the last Parliament. Quite simply, there has been no ‘neo-liberal’ erosion of the welfare state. It has grown and grown and grown – and will continue to do so on unchanged policies, given the demographics and the UK’s system of pay as you go pension and healthcare systems.

3. THE BRITISH GOVERNMENT IS HIGHLY CENTRALISED

In 19th century Britain there grew up a strong culture of local government, with powerful city and regional identities and important politicians whose careers were based in provincial communities. Even in the 1920s and 1930s local government accounted for 45 per cent of total government spending. Now, however, just 25 per cent of government expenditure in the UK takes place at a sub-central level. More importantly, less than 5 per cent of overall government tax revenue is raised at a local level, making us one of the most centralised polities in the developed world. In effect, local government is just a branch office of central government. Central government has the power.

Many competences have moved from the nation state level to the European Union too. The government estimates that around 50 per cent of UK legislation with a significant economic impact originates from EU legislation. In 2009, there was an average net increase of five new EU laws and regulations per day. There’s nothing ‘neo-liberal’ about this high degree of centralisation of government activity.

4. IN THE UK, UNLIKE ELSEWHERE, THE STATE BOTH FUNDS AND PROVIDES SIGNIFICANT SERVICES

While you could argue that the state should fund services for the poor or certain services which might bring societal benefits, such as education up to a certain age, there is nothing to say the state itself should run them. Yet our welfare state, unlike many others, both funds and provides services such as health, welfare and education – giving it a near monopoly in all these areas.

In supposedly ‘neo-liberal’ Britain, the NHS is a state backed monopoly and just 7 per cent of primary school pupils were enrolled in schools not operated by a public authority in 2012. Supposedly ‘social democratic’ countries, often held up by Jones and others, have much more pluralistic provision. In Germany, the independent private sector (including not-for-profit) accounts for more than half of the total number of hospital beds. In Denmark, 15 per cent of primary school pupils are enrolled in schools not operated by a public authority. If neo-liberalism was so dominant here, why haven’t we seen much more outsourcing of state financed activity?

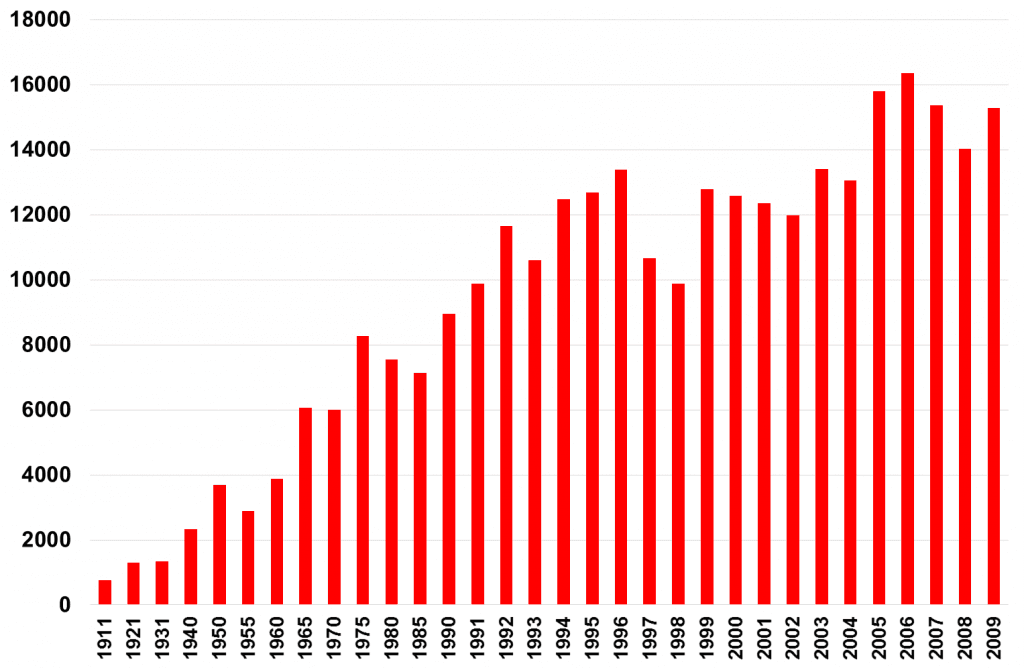

5. REGULATION AND LEGISLATION HAVE GROWN… MASSIVELY

Far from being a deregulated free-market utopia, the degree of legislation and regulation has grown hugely in the UK. The most sensible measure of legislative activity is probably the combined number of pages of acts and statutory instruments. This has been on a clear upward trajectory between 1911 and 2009 (and this excludes separate Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish legislation).

Pages of Acts and Statutory Instruments (1911 to 2009)

13 per cent of all UK jobs now require some form of licensing, registration or certification from government – a proportion that has doubled in the last decade or so. The employment of temporary workers and migrants has been subject to increasing levels of regulation. Mandated benefits such as parental leave, holidays, and reduced working time have been introduced in recent years. Regulation of financial services has mushroomed since 1986, before which the government had virtually no regulatory role in most parts of the financial sector. The number of regulators has increased from 1 for every 11,000 people employed in the financial sector to 1 for every 300 in just thirty years. If it carries on at that rate for another 60 years, there will be more financial regulators than people working in finance – and that excludes compliance officers working for private firms.

CONCLUSION

In the UK then, government spending is historically high and the scope of the state – especially the welfare state – has grown massively over the past century. Our system of government is highly centralised and concentrated, with the state having near monopolies in many public services (unlike other Western countries). The extent of regulation and legislation has grown – hugely.

Owen Jones claims that “dog-eat-dog neoliberalism…reigns today”. It doesn’t. We don’t comment on whether we have a dog-eat-dog society. We hope not. But, if we do, it is dog-eat-dog social democracy. Which shows why organisations like the Institute of Economic Affairs, who articulate the need for a more classical liberal approach to the economy and public services, are needed now more than ever.

Today, on our 60th anniversary, we hope that you can join us in celebrating what free market economics has achieved in terms of wealth creation, poverty reduction and improved quality of life around the world. But this shouldn’t allow us to become complacent about the future. The facts outlined here show that there is still much to do.

Ryan Bourne is Head of Public Policy at the Institute of Economic Affairs

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.