One of my favourite National Trust properties is Overbeck’s in Salcombe – the former seaside home of an eccentric inventor with a wondrous subtropical garden. The last time I visited, the nice lady at the entrance asked – as they always do – whether I might consider taking out a family membership.

“Sorry,” I said. “But I’d rather eat worms.”

She probably didn’t want to hear but I told her anyway. For years, like so many parents with younger children in need of distraction, I’d used the National Trust’s myriad glorious properties as the perfect weekend refuge: delicious teas, well-stocked bijou gift shops, historic houses with magnificent grounds to explore and play in. Joining the National Trust clearly made sense – with the added bonus that I’d be doing my bit to preserve the crumbling fabric of England and Wales’s heritage.

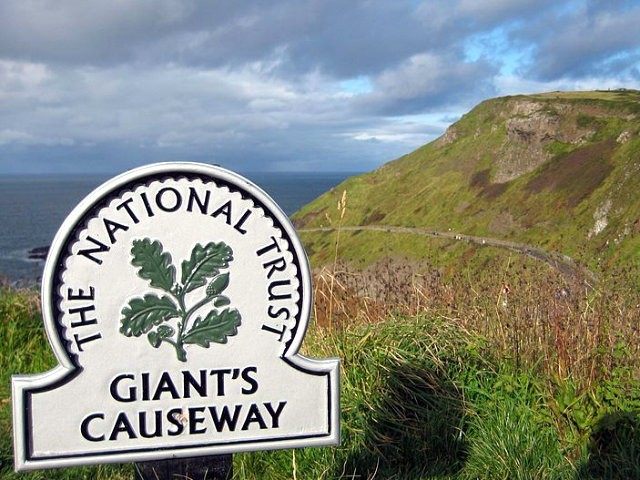

Unfortunately, I went on to explain, the National Trust had now been hijacked by left-liberal entryists completely out of touch with this once-splendid organisation’s charitable purpose. No longer, it seems, is the National Trust about preserving the glories of the English country house, connecting us with our past and conserving the 775 miles of coastline it owns.

Rather, it has been turned into yet another progressive activist organisation advancing political causes which are irrelevant to – and often inimical to – its charitable remit.

You could argue that the rot set in when it banned fox hunting on its land. But the moment it really started going downhill was in 2012 with the appointment of its new director-general Dame Helen Ghosh.

Ghosh is a classic beneficiary of the revolving door system whereby time-serving quangocrats with the appropriate politically correct views are shuffled from plum post to plum post regardless of their aptitude for the job.

A career civil servant with no particular expertise in or natural sympathy with heritage issues or the countryside Ghosh is, as Quentin Letts notes in this delightfully catty profile, “more at home in court shoes than gum boots”. She also has a reputation – Letts delicately hints with more generosity than I’m prepared to allow the dreadful woman – for being pretty low-grade and thick.

In other words, she would have been ideal for somewhere grisly and right-on and pointless like the Equality and Human Rights Commission, but could scarcely be more wrong for a charity whose meat and drink is toffs, antique furniture, well-spoken old ladies in tweed twin sets, and oak studded parkland, and whose membership largely comprises small ‘c’ conservatives.

Just how utterly unsuitable for the job she is, Ghosh has revealed in her organisation’s announcement that from now on one of its main priorities will be combating climate change which, it claims, ‘poses the biggest single threat’ to its properties so far.

No, it doesn’t. It simply doesn’t. This is purely an expression of Ghosh’s ignorance and of the misinformation foisted on her by the bien-pensant types in whose company she prefers to spend her time.

And if this were merely a case of a silly woman venturing a foolish opinion, perhaps that would be excusable. Unfortunately, Ghosh’s ignorance and idiocy is being transformed into policy in its vomitously named new strategy document Playing Our Part.

Besides relaxing its objections to wind farms – and if we’re talking about “the biggest single threat” to the British landscape, there’s your badger – the National Trust has announced a “20 per cent reduction by 2020” of its energy use “with 50 per cent coming from renewable sources on the land we look after.”

Ghosh says:

“We will be meeting our commitment predominately from hydro schemes, and with biomass boilers at a number of our big houses. And we do have the occasional turbine. We do not object in principle to wind turbines in the right place. In sensitive historic environments, wind turbines are not the thing to do, but I think we object to two per cent of all wind turbine applications nationally.”

And almost inevitably, Ghosh agonises that the organisation is too middle-class and wants to make it “more relevant” to its membership.

She wants to move away from country houses and more towards the places like the childhood homes of Paul McCartney and John Lennon (because of course, if it weren’t for the National Trust it would have occurred to no private enterprise to turn them into museums, would it?).

“It’s things like the Beatles’ houses in Liverpool or back to back houses in Birmingham. And our visitors are absolutely loving them.”

Absolutely loving them. There’s a phrase that tells you all you need to know. But just in case it didn’t, here’s an even better one.

The challenge, she says, is to persuade people that they did not need to feel awkward “if they didn’t know who George II was.”

Yeah, that’ll be it, Dame Helen. Until you came along, the National Trust was going to hell in a handcart: four million members, almost of all them inexcusably middle class with an unforgivable predilection towards stately homes, denying social justice to all those disenfranchised ordinary folk who feel so alienated by the mention of any historical figure who isn’t Mary Seacole that the thought of visiting a National Trust property makes them come over like Damien in the Omen when his parents try to take him to church.

And if it’s signs of the End Times we’re looking for, I reckon that for our system to have allowed a creature like Helen Ghosh to get her claws on something as cherishably middle class, civilised and quintessentially English as the National Trust must be pretty near the penultimate one. All it requires now is for the ravens to leave the Tower and then that’ll be it: game over.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.