It shouldn’t be controversial, should it, to honour the men and women who suffered and died, in inconceivable numbers, in the First World War? But, with each year that passes there seem to be more and more idiots out there in the media, nudging at the question, seeking to undermine the obvious necessity of memorialising our dead, attempting to politicise a history they take no time to properly understand.

I’ve been invited to debate the subject at the Cambridge Union in October. The motion is: “This House Believes that WWI has been unnecessarily glorified.” I think you can guess which side I’m on. What amazes me is that the Union has managed to find anyone to propose the motion.

For some Breitbart London readers, the fact that the trades unions, the womens’ suffrage movement and left-wing Cambridge philosophers were among the more prominent contemporary critics of the First World War will be enough to convince them of the war’s merit and of the continuing reverence we should have for it. But let me sketch out an argument for the rest of you.

The reason we remember fallen heroes is that they were indeed heroes. Their deaths rid the world of the German threat for the first (alas, not the last) time in Europe’s history, smashed the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires and fatally weakened Russia. At least two of those four powers remain in some form our greatest geopolitical threats today, albeit in substantially weakened circumstances. We have our fallen men to thank.

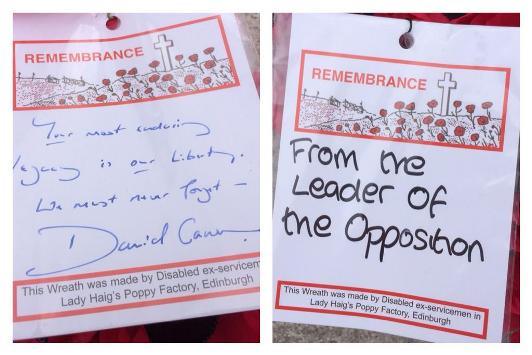

It is deeply unfashionable to “glorify” war at places like the BBC and on the pages of the Guardian, where it can sometimes seem as though any wacky opinion, provided it is sufficiently anti-British, will get a hearing. But it bears repeating, because some people have forgotten: we were and are the good guys. And we won. The freedoms we enjoy today were secured for us by a braver, older generation. They are the consequences of our victories in the First and Second World Wars.

It’s possible to characterise World War One as an ugly clash of imperfect Empires, and I have some sympathy with that view. But, with due respect to our friends elsewhere in the world, the Empire left standing at the end was the right one.

To be sure, there’s nothing very glorious about the entanglements we’ve found ourselves in throughout the Middle East in recent years. Whatever your view of the Iraq war, it’s saddening to realise how little we’ve learned. But it shouldn’t be contentious to honour a war in which so many people died to uphold the principles and values of the Anglosphere–even if no one realised at the time that’s what they were doing.

Because those principles and values are better than the principles and values of the people we fought and continue, today, to fight around the world. Britain, and later our progeny, America, have together been responsible for forging most of what is good about the world in which we now live. We have been champions and cheerleaders of liberty, democracy, enterprise and prosperity. Not enough people say that out loud and unvarnished. They should.

We ought to be proud of our grandparents and great-grandparents, who gave their lives to fashion a world that is, all things considered, a pretty swell place to live, thanks in large part to the export of British culture and British values to the four corners of the globe. (Those bits of the world that reject the British model of freedom and democracy are, unsurprisingly, the places people don’t even want to visit on holiday.)

It’s not just the broad-brush political ideals, either. “Let light shine out of darkness,” Corinthians reminds us. And though it can seem almost obscene to talk about poetry and technological advances in the context of such a devastating loss, for what are wars fought, if not culture, progress and the defence of our way of life? Our literary heritage and technological prowess in this country were both immeasurably enriched by the awful tragedy of the Great War–something we have only really come to understand with hindsight. It’s worth being grateful for them, too.

It seems to me that if we accept the view that the First World War and all its horrors should be buried and forgotten–that it is in some way a cause for shame and not solemn gratitude–we forgot not only the unimaginable sacrifice made by so many young men in the service of our way of life, but also the great gifts that loss gave us, too. Air traffic control, drones and mobile x-ray machines. Sassoon, Owen and Rosenberg.

Testaments to the advances that can be made when a nation pulls together, and extraordinary artefacts of human experience in times of horror, respectively, the technology and literature the First World War bequeathed to us should stand as a tribute to the sacrifices those men made. But, as I say, most of all–and this goes for both wars–we should remember: there’s no shame in winning.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.