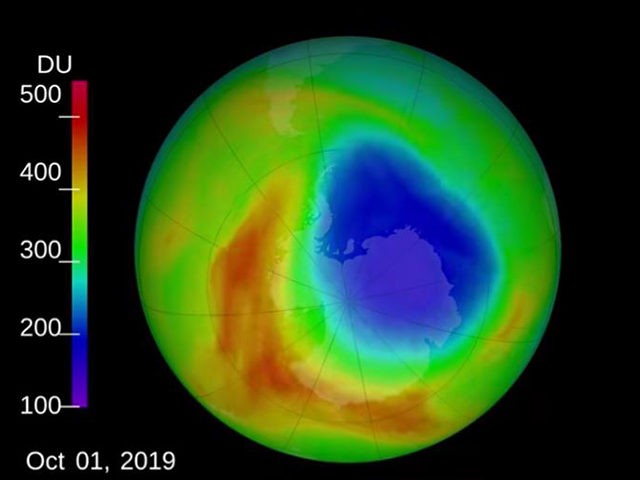

The hole in the ozone has reached its smallest size since scientists discovered it in 1982 due to unusual weather patterns in the upper atmosphere above Antarctica, according to NASA.

The hole fluctuates every year and is usually largest during the coldest months in the southern hemisphere, between late September and early October.

The latest observations from space show that the hole reached its annual peak of 6.3 million square miles and then diminished to less than 3.9 million square miles during late September and early October, a record low for a hole that typically grows to a maximum area of eight million square miles.

Researchers say this year’s small size was due to a warming event in the stratosphere, which disturbed the ozone-thinning process.

“It’s great news for ozone in the Southern Hemisphere,” Paul Newman, chief scientist for Earth Sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in a statement. “But it’s important to recognize that what we’re seeing this year is due to warmer stratospheric temperatures. It’s not a sign that atmospheric ozone is suddenly on a fast track to recovery.”

It is the third time in 40 years in which warming halted ozone depletion, as similar weather patterns led to unusually small ozone holes between 1988 and 2002, the Washington Post reported.

“It’s a rare event that we’re still trying to understand,” Susan Strahan, an atmospheric scientist with the Universities Space Research Association, said in a statement. “If the warming hadn’t happened, we’d likely be looking at a much more typical ozone hole.”

But researchers added that these scientific events are not linked to climate change.

The weather systems that disrupted the 2019 ozone hole, known as “sudden stratospheric warming” events, were 29 degrees higher than average. NASA said this weather event also helped to weaken the Antarctic polar vortex — a high speed of air which circles around the South Pole.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.