The literary magazine Guernica has retracted an article published by a left-wing Israeli writer about finding “common ground” with Palestinians because the story was deemed not to be anti-Israel enough by the editors of the magazine.

The New York Times reported:

In an essay titled “From the Edges of a Broken World,” Joanna Chen, a translator of Hebrew and Arabic poetry and prose, had written about her experiences trying to bridge the divide with Palestinians, including by volunteering to drive Palestinian children from the West Bank to receive care at Israeli hospitals, and how her efforts to find common ground faltered after Hamas’s Oct. 7 attack and Israel’s subsequent attacks on Gaza.

It was replaced on Guernica’s webpage with a note, attributed to “admin,” stating: “Guernica regrets having published this piece, and has retracted it,” and promising further explanation. Since the essay was published, at least 10 members of the magazine’s all-volunteer staff have resigned, including its former co-publisher, Madhuri Sastry, who on social media wrote that the essay “attempts to soften the violence of colonialism and genocide” and called for a cultural boycott of Israeli institutions.

Chen said in an email that she believed her critics had misunderstood “the meaning of my essay, which is about holding on to empathy when there is no human decency in sight.”

The original essay is still available at the Internet Archive. Here are some of the passages that Guernica sought to suppress (original emphasis):

My own heart was in turmoil. It is not easy to tread the line of empathy, to feel passion for both sides. But as the days went by, the shock turned into a dull pain in my heart and a heaviness in my legs. At night, I lay in bed on my back in the dark, listening to rain against the window. I wondered if the Israeli hostages underground, the children and women, had any way of knowing the weather had turned cold, and I thought of the people of Gaza, the children and women, huddled inside tents supplied by the UN or looking for shelter. I stared up at the ceiling and imagined it moving closer and closer toward me. Not falling or collapsing but moving, like an elevator descending into the ground.

The horrors that had been perpetrated rose to the surface of my consciousness at these times. I listened to interviews with survivors; I watched videos of atrocities committed by Hamas in southern Israel and reports about the rising number of innocent civilians killed in a devastated Gaza.

…

Two weeks after the present war began, I took the plunge and again began driving [Palestinian] children to hospitals. My own grown-up children were against this, but I was determined to go. The night before my first drive since the war started, my husband and I decided he would accompany me, just in case. My son scoffed at this: Go on your own if you must, he said wryly. If anything happens, we don’t want to lose both our parents. We woke up at 5:00 a.m., made coffee, and waited for the coordinator to give me the go-ahead. The rules had changed: instead of waiting for them in the parking lot of Tarkumia, I was instructed to leave the house only when my passengers had gotten through security. At 6:30, I got the call, and we drove in silence to Tarkumia. The road leading to the checkpoint was deserted; since October 7, Palestinians had been forbidden to leave the West Bank for work in Israel.

We arrived at the parking lot, and I got out of the car. A small boy with a shock of black hair and his father were waiting at the other side of the parking lot. I hesitated as a soldier came up to me, and I fumbled for my driver’s license and the details of my passengers, sent to me earlier: Jad, age three, accompanied by his father. Suddenly, the little boy waved to me from across the way, and I waved back as they walked over to my car. The father spoke a little Hebrew. We introduced ourselves, quickly strapped Jad into the booster, and drove away. Ten minutes later, I dropped my husband off at the junction below my house. I felt safe. I was doing the right thing. This boy deserves medical treatment; he is not a part of the war, I thought. On this first journey, I focused on only the job at hand: to get Jad to the hospital. An hour later, I said goodbye to them outside the pediatric unit of Sheba Medical Center. While the father busied himself removing an overnight case from the trunk of my car, I unbuckled Jad from the booster, and he held out his arms and smiled up at me. Shukran, shukran, thank you, the father said as I cradled Jad in my arms for a moment. And I wanted to say, No, thank you for trusting me with your child. Thank you for reminding me that we can still find empathy and love in this broken world. I followed them with my eyes as they disappeared behind the glass doors of the hospital, and then I switched the radio on.

Madhuri Sastry, one of the publishers who resigned, called Chen’s essay “a hand-wringing apologia for Zionism and the ongoing genocide in Palestine” (a claim flatly contradicted by the actual content of the story, as shown above).

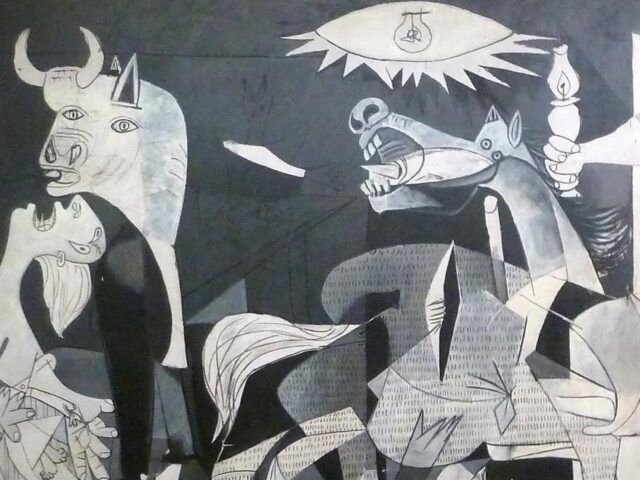

Guernica, which is the name of a city in Spain and also the title of an iconic anti-war painting by Pablo Picasso, indicates in an editor’s note where the article used to be: “Guernica regrets having published this piece, and has retracted it. A more fulsome explanation will follow.”

Joel B. Pollak is Senior Editor-at-Large at Breitbart News and the host of Breitbart News Sunday on Sirius XM Patriot on Sunday evenings from 7 p.m. to 10 p.m. ET (4 p.m. to 7 p.m. PT). He is the author of the recent book, “The Zionist Conspiracy (and how to join it),” now available on Audible. He is also the author of the e-book, Neither Free nor Fair: The 2020 U.S. Presidential Election. He is a winner of the 2018 Robert Novak Journalism Alumni Fellowship. Follow him on Twitter at @joelpollak.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.