This week, I traveled briefly to Toronto, Canada, to see my young cousin perform in the visiting London production of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat.

My mother first took me to see it in Chicago when I was five years old, and I fell in love with the music and the story. It helped me develop a love of the Bible, and I have enjoyed seeing various other productions of the musical for 40 years.

It so happens that this week, Jewish congregations around the world will read the story of Joseph, as part of the annual cycle of Torah readings, or portions. The portions that involve Joseph happen to fall around the time that the festival of Chanukah (or Hanukkah) is observed, which means the story also tends to coincide with the holiday of Christmas.

In fact, the story of Joseph has deep resonance with both of these holidays.

To start with Christmas: Joseph is also the name of the father of Jesus. There are other parallels: Joseph’s mother Rachel, Jacob’s favored wife, died near Bethlehem; later, the Joseph of the New Testament has his son in Bethlehem.

Like the Joseph of Genesis, Jesus endures struggle and humiliation on the way to his destiny; he, too, is betrayed for a few silver coins; and his sacrifice, too, paves the way for a redemption.

Both stories involve predictions of political power being fulfilled — by a prince of Egypt, or a prince of peace.

The story of Chanukah also has some common themes with the story of Joseph.

Both are stories of the few and the weak overcoming the many and the strong. Joseph prevails over his other eleven brothers as he is elevated — despite being a mere Hebrew slave, and a prisoner — to be Pharaoh’s second-in-command.

The story of Joseph has an additional parallel to Chanukah that makes it particularly poignant. Chanukah is partly about the challenge of adapting Judaism to secular surroundings, a task that is — ironically — more difficult in a tolerant society.

Alexander the Great is revered by Jewish tradition — to the point where “Alexander” became a Hebrew name — because he let the Jews of ancient Israel practice their faith. But Hellenic culture also enticed many Jews to abandon their traditions.

Joseph is regarded as a model for Jewish adaptation to a world in which we are a minority. He obeys the prevailing law of Egypt; he is, in fact, an Egyptian patriot and leader; yet he never compromises his own principles, refusing to violate Jewish ethical constraints (e.g. refusing to commit adultery with the wife of Potiphar). He balances both worlds.

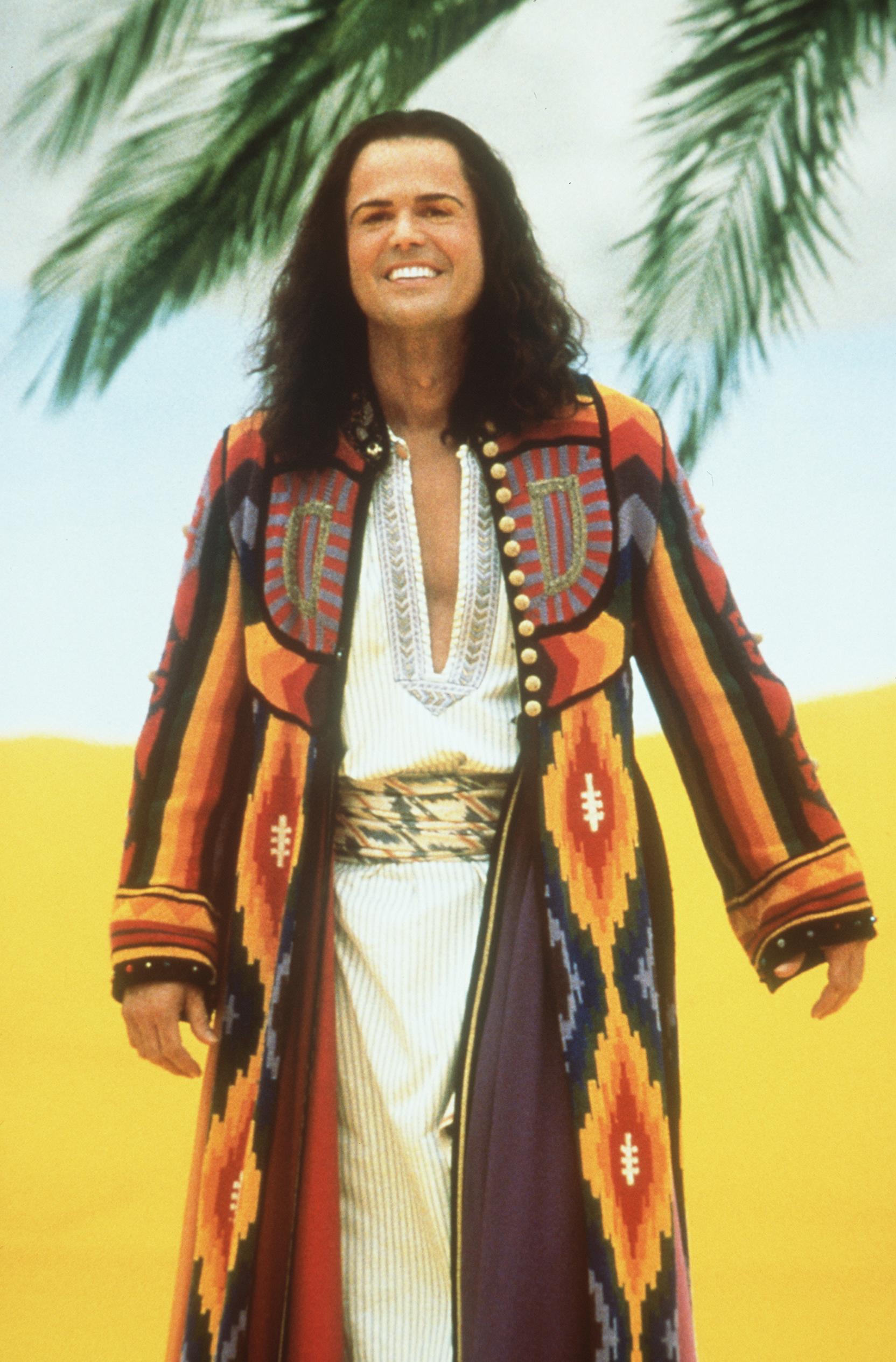

Donny Osmond Stars In Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “Joseph And The Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat,” 1990s (Photo By Getty Images)

Joseph is widely admired across faiths — even in Islam, as Yusuf. That does not mean every “Joseph” is a good one, or that leaders named Joseph (or “Joe”) necessarily follow his example. Josef Stalin was among the most evil people ever to have existed, for example.

The key is whether they submit their will and wisdom to God, which Joseph does in Genesis, giving public credit to God for the good decisions he makes.

Then there is simply the beauty of the story. I have read the story of Joseph countless times; yet I feel a lump in my throat every time I read about his reunion with his brothers.

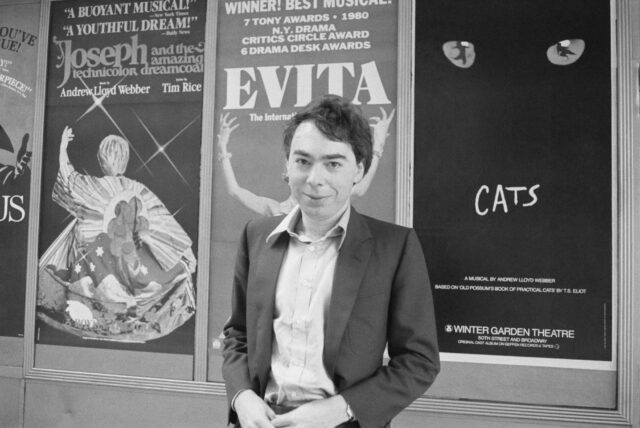

A portrait of composer Andrew Lloyd Webber standing in front of billboards advertising his three musicals Joseph and the Technicolor Dreamcoat, Evita, and Cats. (Getty)

There is something so poignant about the Bible’s assurance that each of us has a mission in life that may not be apparent in the moment, but will eventually be made clear — a reason for the struggles, a purpose to the unusual twists of fate.

That is the secret of the appeal of Joseph, the musical, more than a half century after it made its debut.

There are so many memorable songs, but the one that focuses directly on faith is “Close Every Door to Me.” Presented at the end of the first act, it shows a despondent Joseph, in prison, at the lowest point in his life. He begins by condemning himself to insignificance: “If my life were important/I would ask, will I live or die?”.

Yet he concludes by remembering that when he is forgotten by the world, and even by his family, there is One who will never abandon him: “Children of Israel/Are never alone/For we know we shall find/Our own peace of mind/For we have been promised/A land of our own.”

There it is again: that lump in the throat.

Enjoy that musical, and you will also understand everything I believe in this world, and where it comes from.

Joel B. Pollak is Senior Editor-at-Large at Breitbart News and the host of Breitbart News Sunday on Sirius XM Patriot on Sunday evenings from 7 p.m. to 10 p.m. ET (4 p.m. to 7 p.m. PT). He is the author of the recent e-book, Neither Free nor Fair: The 2020 U.S. Presidential Election. His recent book, RED NOVEMBER, tells the story of the 2020 Democratic presidential primary from a conservative perspective. He is a winner of the 2018 Robert Novak Journalism Alumni Fellowship. Follow him on Twitter at @joelpollak.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.