For mainstream American audiences, the late Stanley Kubrick wasn’t the most accessible director of his time. There is no question, though, that his influence is still everywhere in modern film.

How many filmmakers working today have been influenced or mentored in some way by Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, or Woody Allen? According to the numerous documentaries that come with Stanley Kubrick: The Masterpiece Collection, the influence Kubrick had on that Hollywood trinity was personal and profound.

He may have been cheated out of a Best Director Academy Award too many times to count, but Kubrick matters. If you love movies and the language of movies, this one-of-a-kind director – who enjoyed the kind of artistic and budget freedom Scorsese and Spielberg would kill for – is a part of modern cinema’s DNA like no other.

There are many Kubrick movies I outright love and did so at first sight: “A Clockwork Orange” (1971), “Dr. Strangelove” (1964), and “Full Metal Jacket” (1987) are three of those included in this collection (three others: “The Killing” (1956), “Paths of Glory” (1957), and “Spartacus” (1960), are not). Like any great relationship, the more time I spend with those movies, the more I appreciate, cherish, and love them.

There are also Kubrick movies that at first I didn’t like so much. Still, again and again, I was drawn back to them. The failure to appreciate them felt like a failure on my part. There was a code to crack, and it was up to me to crack it. Patience and repeat viewings have finally enamored me of “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968) and “The Shining” (1980).

“Barry Lyndon” (1975) is still out of reach. I will, however, keep trying and have all the confidence things will eventually click.

“Eyes Wide Shut” (1999), Kubrick’s final film, and “Lolita” (1962), have a lot going for them. Unfortunately, both do miss the mark. I’ll talk more about that below.

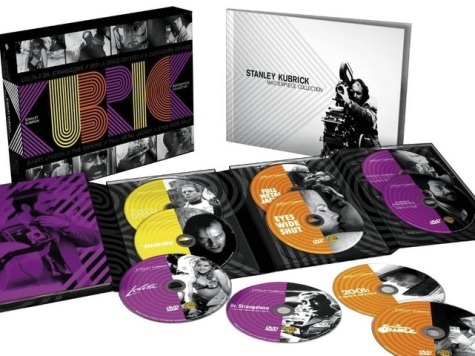

This 10 disc collection, which also includes a 78-page hardcover book and six terrific documentaries, is absolutely splendid. The packaging and presentation are coffee table-worthy, and the content promises countless hours of discovery and years of re-discovery.

From what I can tell, on top of new features like the in-depth documentary “Kubrick Remembered,” all the special features from previous DVD and Bluray releases have been gathered together here. There’s even the 2006 documentary O Lucky Malcolm! that focuses on the entire career of actor Malcolm McDowell, who starred in only one Kubrick film, “A Clockwork Orange.”

—

Here is a chronological rundown of the films that come with the set. Needless to say, the high-definition transfers are stunning.

Lolita (1962)

Kubrick turns this famous tale of dark and forbidden sexual obsession into a black comedy. It was 1962, after all, and he really had no other choice. Lolita isn’t just about sex; it’s about the middle-aged Humbert Humbert’s (James Mason) sexual desire and eventual affair with a 14-year-old-girl.

Everyone talks about Peter Sellers’ role as the endlessly depraved Clare Quilty. He’s certainly memorable. As Lolita’s desperately lonely mother, Shelley Winters is the film’s true marvel. The emotional devastation she displays after finding Humbert’s diary is so effective you really do buy the way she dies immediately afterward. In lesser hands, that (necessary) plot turn would feel terribly contrived.

According to the collection’s documentaries, due to the censorship restrictions of the day, Kubrick came to regret directing Lolita, and it’s hard to blame him. There’s no question he succeeded like few others could have in communicating the more sordid aspects of the novel. As much as you want it to, though, using comedy to compensate for Humbert’s destructive and desperate passion just doesn’t work. Director Adrian Lyne’s 1997 remake is far superior.

Dr. Strangelove (1964)

In one of the documentaries, Woody Allen notes that despite what he sees as some flaws in the writing and performances, Kubrick’s extraordinary direction and decision to adapt a dramatic novel into a dark comedy is what makes Strangelove a bona fide masterpiece, one of the greatest films ever made.

What’s also true is that this hilariously funny and irreverent Cold War comedy is where Stanley Kubrick became Stanley Kubrick. Every film of his that came before had the stamp of a brilliant and visionary director, no question. Strangelove, however, set the template for the visual rigor that would go on to define the director. Kubrick’s meticulous pre-production planning, his set design, and camera placement all come together as signature. Kubrick came into his own in 1964, and thankfully he was just getting started.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Anyone who’s been reading me for any period of time knows that for decades 2001 has eluded my grasp. Despite numerous viewings, I could never get what all the hoopla was about. Kubrick’s wildly ambitious and undeniably gorgeous examination of the evolution of man from monkey to star child simply bored me stiff.

That all changed last week. My stubbornness finally paid off.

One of Kubrick’s trademarks is his ability to put the viewer in a trance. His best films transform you, and this magic is created by lengthy scenes and sequences, and also allows for them.

Sitting in my darkened home theatre with no deadlines on my mind and no iPhone in my hand, and surely aided by a stunning high-definition transfer, 2001 finally grabbed hold of my heart and soul last Saturday morning.

I can’t wait to see it again.

It was for special effects that still dazzle and hold up better than any modern CGI that won Kubrick his only competitive Oscar.

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

My favorite Kubrick movie and one that only gets better with repeat viewings.

On a purely thematic level, Clockwork is one of my all-time favorites, period. Despite all the bad publicity surrounding the violence the movie supposedly inspired (death threats against Kubrick resulted in the film being pulled from theatres in his adopted home country of England), the mind-blowing story of Alex DeLarge (an unforgettable Malcolm McDowall) and his sociopathic band of droogs is in reality a profound (albeit complicated) story about the beauty and importance of the human spirit.

Kubrick pulls no punches in the portrayal of our protagonist and his depraved love of the “ultra-violence.” Alex is a casual murderer, rapist, and home invader. At random, he preys on the innocent and in one highly stylized and unforgettable scene after another, we witness humanity at its nihilistic worst.

Then the twist comes.

Had Alex been tried and executed for his crimes, moviegoers might have felt bad for the lost potential of youth but undoubtedly felt justice has been done. Kubrick (working from a novel by Anthony Burgess) has bigger ideas on his mind. To remind us and reinforce to us the importance of the human spirit, Alex is put through a rehabilitation program that springs him from jail but costs him his free will.

Suddenly, instead of being horrified by the charismatic Alex, we the audience are brilliantly manipulated into sympathizing with him. One of the most despicable and unrepentant characters ever conceived earns our sympathy because he’s no longer free to choose his own destiny, even if it involves victimizing another.

Another delicious twist is the character of the priest. When we first meet this prison minister, Kubrick pulls a head fake by making him the subject of ridicule. If you watch closely, though, he is the conscience of the story — the only man who understands and opposes Alex’s “rehabilitation.” In Clockwork Orange, it is a Christian man of the cloth fighting for a reprobate’s right to free will and against forcing him to behave morally.

Clockwork also has important things to say about revenge and political/government corruption.

This is filmmaking at a level few have or will ever achieve. Like the Bible, A Clockwork Orange uses horrific sex and violence to deliver a deeply moral and Christian message.

Barry Lyndon (1975)

A beautifully filmed (lit mostly by natural candlelight) look at aristocratic social-climbing in 18th-century England… that lasts three hours.

I know for a fact that Barry Lyndon is a masterpiece. and that the failure to fully appreciate it is my fault. I’m going to keep trying because when it clicks like 2001 did last week, it just doesn’t get any better than that.

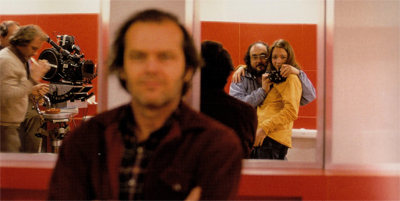

The Shining (1980)

Stephen King hates Kubrick’s adaptation of his best-seller, and so did I for decades. This meticulously filmed tale of all work and no play turning Jack Nicholson into a crazed, ax-wielding lunatic is now mandatory viewing at least once a year.

There’s nothing scary about Kubrick’s only deep-dive into the horror genre. It’s not even suspenseful. What grabs you is the spell Kubrick conjures. You get lost in the story, the hotel, the madness. The Shining is a transportation device, as are all our favorite movies.

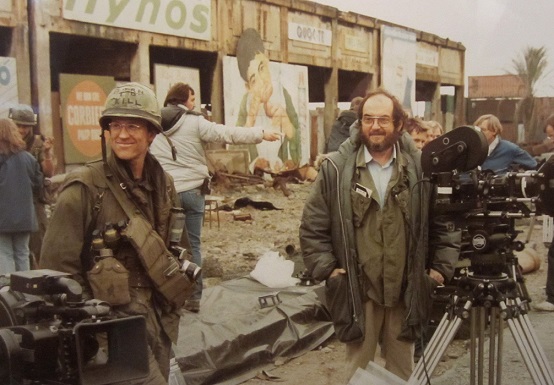

Full Metal Jacket (1987)

The second half of Kubrick’s harrowing and heartbreaking anti-war film is jaw-droppingly brilliant. In any other movie, these 60-or-so incredible minutes would stand out in our collective cinematic memories in the same way the first minutes of Saving Private Ryan (1998) has for more than 15 years. Incredibly, this hour feels like something of a letdown because the first hour of Full Metal Jacket ranks as one of the most mesmerizing hours of film ever crafted.

We never want to leave boot camp. We never want to stop watching R. Lee Ermey’s Gny. Sgt. Hartman bully, cajole, humiliate, and ultimately dehumanize his new recruits. The jarring jump-cut from this climate-controlled, hermetically-sealed world to the too bright, too loud, too busy, and too tragic world of the war in Vietnam is, as Kubrick intended, a disorienting, frustrating, and depressing experience. Suddenly, like these raw Marines, we the audience are where we don’t want to be and we resent the hell out of it.

Full Metal Jacket is as complete an immersive experience as any film ever made. And Kubrick has the courage to make us not like half of his movie, because he wants us to feel just a fraction of what it’s like for the men and women who really do fight our wars.

Matthew Modine’s Pvt. “Joker” is our protagonist and, because he’s us, he’s intentionally bland. Ermey owns the first half of our story. The second half is owned by Adam Baldwin (full disclosure and brag: a friend of mine) who tears up the screen creating the now-iconic character of Animal Mother.

Kubrick’s Paths of Glory (1957) is only the second greatest anti-war film ever made because of Full Metal Jacket. Believe it or not, the former is much more cynical (probably because it’s based on a true story). Metal is neither anti-troop, anti-military, or anti-American.

Kubrick isn’t telling us what’s right or wrong.

He’s simply showing a hard truth of what can be required to win (or lose) a war.

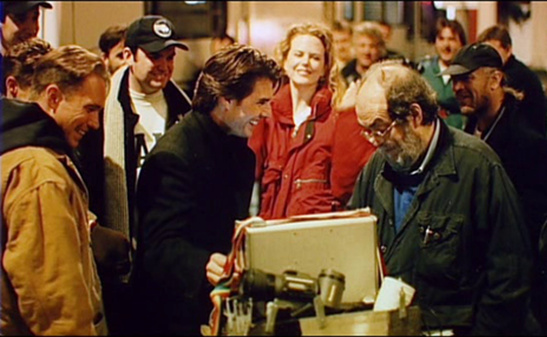

Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

Sadly, Kubrick’s final film is also his worst. The direction is meticulous. The production design recreating (a somewhat artificial) New York City and the elite lofts where Manhattan’s Masters of the Universe dwell, is gorgeous. The performances by Nicole Kidman, Tom Cruise, Sidney Pollack and company are all spot on. The problem is the story. We’re too distanced from the characters, and whatever theme Kubrick was after is impossible to grasp.

Kidman and Cruise play an upper-crust married couple (they were married in real-life during production) who seem to have it all. A night of too much champagne and flirting with others results in a confession that drives Cruise’s medical doctor into the night, where he discovers the seedy underbelly of illicit sex in Manhattan – something that pulsates equally among the super-rich and poor.

Eyes Wide Shut is lovely to look at (as is Kidman). Personally, human sexuality bores me to tears. It’s the most narcissistic of movie themes and the most tedious. I’ve read that Kubrick (who himself was a devoted family man) wanted to explore marriage, not sexuality. Apparently, sexuality was the vehicle he intended to use to explore marriage. I don’t doubt Kubrick’s intentions. Things just didn’t play out as planned.

Eyes Wide Shut is slow without being mesmerizing, and therefore is dull. A few individual scenes (especially those with Pollack) are quite special. As a whole, Eyes is a curio for Kubrick fans only.

—

For five decades, Kubrick did things his own way, and in the end his batting average was nearly perfect and better than any other director’s, including Hitchcock, Ford, Hawks, and Welles.

This terrific limited edition collection — along with individual Blurays of Spartacus, The Killing and Paths of Glory — is the complete package of the works of a literal genius.

—

Stanley Kubrick: The Masterpiece Collection (Blu-ray) is available at Amazon.com

John Nolte on Twitter @NolteNC

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.