On Tuesday, Sept. 15, Kimberly Guilfoyle of Fox News’ The Five picked the 2014 war documentary The Hornet’s Nest as her “One More Thing” at the end of the show, describing how it told the story of American troops on a dangerous mission in Afghanistan.

Perhaps she saw the film, released around Memorial Day, when it premiered on television on September 11 on cable’s American Heroes Channel. It repeats there at 2 p.m. ET on Monday, September 22, and at noon ET on Sunday, September 28. As of Sept. 9, it’s also available on Blue-ray, DVD, and Digital.

Here’s a trailer:

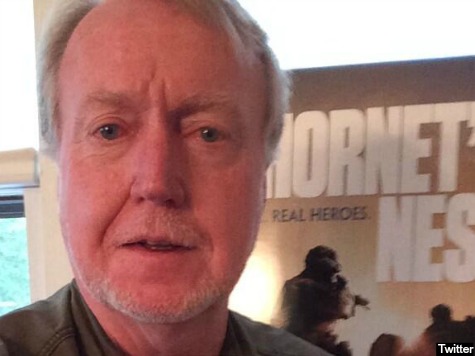

In the middle of a day in which he’s working with journalism students as a visiting professor at the University of Oklahoma, filmmaker Mike Boettcher–a longtime American journalist and war correspondent–tells Breitbart News why he and his news-producer son Carlos Boettcher were embedded with U.S. forces in combat.

“I’ve been doing this more than 34 years as a foreign correspondent,” he says, “going in and out of war zones. Then, after 9/11, I was going to Afghanistan. Then, in 2003, Iraq came, and there was this intense coverage.”

He added, “Then, all of a sudden, everything dropped off the map. I felt, really, by 2006, actually 2005, we just weren’t telling the stories of our men and women in uniform that had gone over.”

Boettcher spent 20 years working at NBC, then 10 at CNN, and he’s been at ABC since 2009.

“We had close to 200,000 troops deployed between Afghanistan and Iraq,” he states. “I felt that we should go back to old traditions set by our predecessors, like Ernie Pyle, who spent an enormous amount of time with Joe on the front lines. I said, ‘We should go back to those traditions. If we, as a country, are going to commit these troops, we damn well better tell these stories.’ That’s why I ended up doing what I was doing, spending more than two years trying to tell stories.”

Boettcher had an agreement with ABC to retain rights to the film, with the twin goal of making an up-close-and-personal documentary about American soldiers, and to spend time with his adult son, who often missed his globe-trotting father while growing up.

But the film has another side benefit: it shows the importance of being there in telling war stories. With the recent ISIS beheadings of two American journalists, Catholic James Foley and Jewish Steven Sotloff, both freelancers, it raises questions about independent correspondents on the front lines, where perhaps network reporters–and their employers–fear to go.

While Boettcher doesn’t think that major news operations will abandon war zones, he says, “I see much more care taken in just the Wild West zones like going into Syria and stuff. The networks and major newspapers, a lot of them are already very cautious about that.”

Boettcher points out, though, that when you’re embedded, you have the automatic protection of the military forces around you.

“The way I see it,” he says, “what embedding allowed me to do in Afghanistan was to get to places you can’t get to, other than with U.S. forces going in. Critics of embedding say, ‘You become biased,’ and I say, ‘Look, I stay as objective as I can, but I’m American; I’m covering U.S. forces; and I’m going to tell their story, good or bad.'”

Continuing, he asserts, “But, really, the other thing is, too, I can’t get to far northeastern Afghanistan to see what’s going on in Kunar Province or Nuristan, unless I’m going with U.S. troops because, if I drive on my own, I’m going to get kidnapped, and my head’s going to get cut off.”

Boettcher was kidnapped, he says, by guerillas in El Salvador in 1985. Fortunately, an “old pro” at covering the region advised him not to get on his knees.

“So, I refused to get on my knees,” he says, “and that confused them. They beat the hell out of me, but they didn’t shoot me. You can get into those situations everywhere. There are ultraviolent groups everywhere.”

Foley, Sotloff–and now, British aid worker David Haines–did wind up losing their lives, beheaded in videos released on the Internet.

“Freelancers have taken a heavy load,” says Boettcher. “Certainly, I promise you, network news organizations aren’t going to get out of the business totally of covering foreign news or going into dangerous situations. That’s what we’ve done routinely over the years. Are they more careful now, and sometimes, do they so no? Yes. Nothing’s changed with that. In those certain circumstances, it’s picked up by freelancers who don’t have that protection, and sometimes who aren’t very experienced.”

“I didn’t know Steven, but James, I did,” shares Boettcher. “We saw him several times in Afghanistan. He knew what he was doing. But sometimes, what are they getting paid–$150 a story, or something like that? I don’t know, but it’s not much. They take risks.” Highlighting those risks, he says, “Number one, they love the job. But number two, they’ve got to eat. They take risks I wouldn’t take, and I’m probably out there in terms of what Ill do, as much as anybody.”

In a way, Boettcher says, it’s nothing new.

“As journalists,” he says, “we are targets. We were targets of death squads in El Salvador. I was kidnapped. I was a target of the right wing and the left wing in El Salvador. We were targets in Beirut decades ago. People know the power of the camera and what it does. For example, in Afghanistan, if we’re with a patrol, and we’re being ambushed, they will shoot at us first because we’re carrying the camera.” He elaborates by explaining, “They know–and it’s very sad, but it’s true, and you’re seeing it now with the deaths of Foley and Sotloff–that if you kill a journalist, it becomes huge international news.”

As for the ethics of viewing and sharing the videos of the beheading, Boettcher says, “I don’t think they should. I don’t. But that’s like spitting in the wind in this era when everything’s out there. Me, personally, I haven’t even sought it, looked at it, because I know what it looks like. I already know what it shows. I don’t need to see that.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.