In 1944, J.R.R. Tolkien was tickled to receive a charming letter from a twelve-year-old Yankee praising The Hobbit, released seven years prior. It was, said the lad, “the most wonderful book I have ever read. It is beyond description. Gee Whiz. . . . ”

“It’s nice to find that little American boys do really say ‘Gee Whiz’,” the author joked to his son Christopher when he mentioned receiving the note. But surprisingly, his prevailing mood was somber:

I find these letters which I still occasionally get. . . make me rather sad. What thousands of grains of good human corn must fall on barren stony ground, if such a very small drop of water should be so intoxicating! But I suppose one should be grateful for the grace and fortune that have allowed me to provide even the drop.

Those are words, humble and true, that evoke the New Testament, conjuring an image of lost souls looking to quench an almost spiritual thirst. At the very time he wrote them, Tolkien was already deep into the agony and the ecstasy of the creation of The Lord of the Rings, and the intersection of the literary and the spiritual was on his mind. “God bless you beloved,” he told his son by way of signing off, but then tagged on a final, lingering question, one weighing heavily on his work: “Do you think the ‘Ring’ will come off, and reach the thirsty?”

It should be clear now to even the dimmest of critical bulbs that Tolkien’s own craving for heroic romance was hardly unique. Millions of others, equally parched in the modern world, were in dire need of the potent drought he was brewing. After The Lord of the Rings finally appeared, it inspired fan letters from grown adults that matched the enthusiasm of the little boy writing from America decades earlier. In The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien we are mostly denied the original missives, but can frequently read Tolkien’s reactions to them.

To one fan, a Mrs. Carole Batten-Phelps, Tolkien said:

You speak of “a sanity and a sanctity” in the L.R. “which is a power in itself.” I was deeply moved. Nothing of the kind had been said to me before. But by a strange chance, just as I was beginning this letter, I had one from a man, who classified himself as “an unbeliever, or at best a man of belatedly and dimly dawning religious feeling. . . . but you,” he said, “create a world in which some sort of faith seems to be everywhere without a visible source, like light from an invisible lamp.”

That’s a fascinating comment, not only because it’s indisputably true, but for what it says about the genre of fantasy fiction at its very best. So many dismiss fantasy in general and Tolkien in particular as shallow children’s fairy tales, with simplistic nursery-rhyme notions of good and evil, and all of it of little relevance to the modern adult world. And yet here are grown adults, intelligent and erudite, who clearly were affected on some bedrock level by The Lord of the Rings. They speak of a sort of comfort, as if reaching a port in the storm of Life, battered and weary, and of being nourished and refreshed by a Power, “some sort of faith,” a Light “from an invisible lamp,” a “sanity and a sanctity.”

There’s been any number of analyses which attempt to discover and unearth the hidden roots of Tolkien’s genius. The author himself disliked academic dissertations, seeing them for what they usually are: examples of the writer trying to preen and peacock his intellectual superiority over the reader, not by understanding or empathizing but by dissection and vivisection. It’s the difference between a critic taking his audience into a golden field and inviting them to share his wonder at the butterflies coloring the skies with beauty and life, and a grumpy collector showing you a scrapbook filled with those same butterflies pinned and cataloged in monotonous order. Both methods address the same subject — but which truly captures their nature, and is a more accurate representation of Life and Creation?

Tolkien’s work steadfastly resists deconstruction because so much of its power isn’t physical or tangible, and hence cannot be pinned or cataloged or dipped into academic and postmodern formaldehyde. It is spiritual, ethereal, concerned not so much with plot as with Purpose. One of Tolkien’s friends, a priest, read portions of The Lord of the Rings in typescript and told the author that he distinctly felt what he called the “order of Grace” in the tale. The phrase left Tolkien quietly overjoyed.

Lying at the center of this Order, holding it all together like divine mortar, is heroism. Tolkien himself was often moved by scenes he wrote displaying his characters’ “physical resistance to evil,” reverently calling their actions nothing less than “a major act of loyalty to God.” This loyalty, equal parts physical and spiritual, was in turn something that he believed “only becomes a virtue when one is under pressure to desert it.” The world of The Lord of the Rings is filled with great temptations of a sort that don’t lead directly to evil per se, but that lead to the abandonment of the physical resistance — the pain, the suffering — that Tolkien considered so central to his notions of true heroism.

When viewed in this fashion, heroism becomes the heritage not only of the strong and mighty and scary-smart — in fact, frequently it is they who most easily give in to the temptations of power. It should be remembered that among the greatest tragedies of Middle-earth is that even such monstrous villains as Morgoth and Sauron were once forces of great good in the world, veritable angels who ultimately allowed themselves to be corrupted into Lucifers by their anti-heroism, i.e. their disloyalty to God. Much the same can be said of Saruman and the Ringwraiths — all tempted into sowing the seeds of their own undoing.

Conversely, many of the greatest heroes of Tolkien’s legendarium are Hobbits and men who, compared to immortal Elves wielding rings of power from the safety of their forested fastnesses, are weak and low and even wretched. And yet by their “physical resistance to evil” they manage to save the world. “The ennoblement of the ignoble I find specially moving,” Tolkien once wrote. “. . . .I love the vulgar and simple as dearly as the noble, and nothing moves my heart (beyond all the passions and heartbreaks of the world) so much as ‘ennoblement’.”

His use of the word “vulgar” here is interesting. He of course did not mean dirty language or nudity, but common or simple. Middle-earth is a world that rocks to what Tolkien described as “unforeseen and unforeseeable acts of will, and deeds of virtue of the apparently small, ungreat, forgotten.” He was enchanted both in fiction and in life by how ordinary people, through even the most seemingly minor acts of charity, pity or goodwill, could create earth-shaking effects that redounded to the good of Good, and of humanity.

This, of course, immensely echoes Christian, and particularly Catholic, teachings. “Pity,” for instance — which Tolkien once reverently described as “a word of moral and imaginative worth” — appears in the Douay-Rheims Bible no less than fifty times. “Without the high and noble,” Tolkien believed, “the simple and vulgar is utterly mean; and without the simple and ordinary the noble and heroic is meaningless.” The Lord of the Rings is awash in this symbiotic interplay between nobility and vulgarity — it is in fact a large part of its overall charm.

Perhaps Tolkien had such affection for the vulgar becoming noble because he felt that he was once vulgar himself, a “grain of good human corn” who was only spared the fate of spiritually perishing on “barren stony ground” by an act of common, unsung heroism that would both haunt and inspire him for his entire life.

******************

Crying farewell, the Elves of Lórien with long grey poles thrust them out into the flowing stream, and the rippling waters bore them slowly away. The travelers sat still without moving or speaking. On the green bank near to the very point of the Tongue the Lady Galadriel stood alone and silent. As they passed her they turned and their eyes watched her slowly floating away from them. For so it seemed to them: Lórien was slipping backward, like a bright ship masted with enchanted trees, sailing on to forgotten shores, while they sat helpless upon the margin of the grey and leafless world.

******************

“I am one who came up out of Egypt,” Tolkien once wrote. Few people now remember that Tolkien, one of the best-known Catholics of the twentieth century, was not born into the faith.

When he was a young boy, Tolkien’s widowed mother forsook her Baptist heritage and converted to Catholicism in the face of vociferous condemnation from her family. Outraged, they proceeded to cut the desperate, ailing woman off from all financial assistance, leaving her to linger and struggle on for a few more years, all the while steadfastly refusing to recant her religious conversion. She finally died of diabetes at the tragically young age of thirty-four, but not before impressing on her sons the depth of her new-found faith, and not before making arrangements that her two orphaned boys would be taken in by a kindly Catholic priest, sent to college via his auspices, and raised within the mental Lórien of the Catechism and Holy Sacraments.

Throughout a long life filled with many disappointments and temptations, Tolkien remained ever grateful that his mother had, to the point of death, gifted him with the “sudden and miraculous experience” of being thrust into “a Faith that has nourished me and taught me all the little that I know.” By 1941, already neck-deep in the composition of The Lord of the Rings, he was able to write to his son Michael with conviction that, “Out of the darkness of my life, so much frustrated, I put before you the one great thing to love on earth: the Blessed Sacrament…..There you will find romance, glory, honour, fidelity, and the true way of all your loves upon earth.”

Romance, glory, honour, fidelity. On the surface, the words evoke Arthurian legends and other warrior tales of heroic deeds more than Catholic piety. But, as usual, Tolkien chose his words carefully. It was because his mother left him with a priest that he met the woman who would become his beloved wife. He would also, while under the care of that priest, attend college, discover philology, and ultimately become the man who would pen the grand tales that today loom like a monolith over the genre of fantasy fiction.

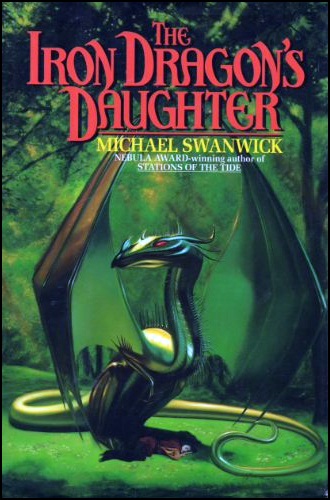

It strikes me that a lot of what our fallen fantasists do these days is as artistically disingenuous as it is morally bankrupt. They claim to be moving the genre forward into refreshingly uncharted territory, and yet virtually everything they do bears the foul-stenched hallmarks of a knowingly maledictory reaction backward to Tolkien and Howard. They consciously use anti-heroics to drain their fictional worlds of virtues like charity, pity, and goodwill, until their tales become metaphorical Death Valleys in which Tolkien’s “grains of good human corn” perish on the “barren and stony ground.” Having done this, they then claim that The Thirst of Tolkien’s fancy is just a myth perpetuated by out-of-touch conservatives wistfully pining for a time that never was.

And yet all the while, the thirsty seek.

Speaking of his characters, both the noble and the vulgar, Tolkien once humbly proposed that, “I lack what all my characters possess (let the psychoanalysts note!) Courage.” But that is not true. He had the courage to spend decades creating a mythology few seemed ready to embrace, and which many were wont to criticize. Just as heroes are ennobled by their courage and convictions, and readers by savoring the tales of their exploits, so too are writers ennobled by telling those tales so beautifully, and by satiating — one precious drop at a time — the eternal thirst that is the bane of good men.

“It remains an unfailing delight to me,” Tolkien admitted, “to find my own belief justified: that the ‘fairy-story’ is really an adult genre, and one for which a starving audience exists.” From a small, vulgar American child going “Gee Whiz!” to a spiritual woman looking for “sanity and sanctity,” from an honest unbeliever’s relishing of the faith that shines out from The Lord of the Rings “like light from an invisible lamp,” to a perceptive English priest savoring the tale’s innate “order of Grace,” all confirm Tolkien’s belief, and drown out the mewling of those unfortunates too irredeemable to realize it.

To Be Continued. . . .

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.