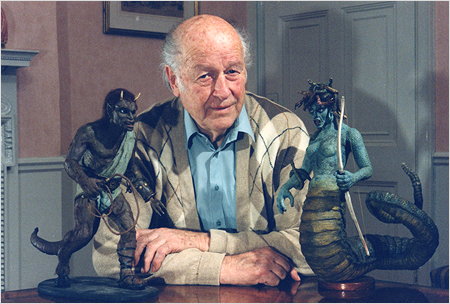

I used to think I was a fan of the genre known today as fantasy, and specifically the subgenres of High Fantasy and Sword-and-Sorcery. This was due to a number of factors. A childhood imagination dominated by Dungeons & Dragons. An exposure to memorable movies like Excalibur, Clash of the Titans, Conan the Barbarian, and their lesser 1980s cousins.

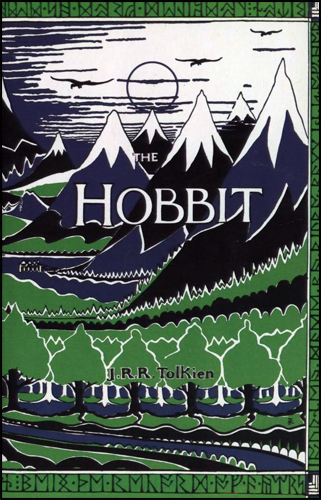

Towering above all, though, was (and still is) my unabashed obsession with the two titanic literary talents chiefly responsible for birthing the entire shebang: J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973) and Robert E. Howard (1906-1936). I consider each the complete equal of the other, two flat-out geniuses destined to be remembered and reread hundreds of years after the Pulitzer-winning authors praised by most mainstream critics are forgotten.

But it was only recently, after decades of ever-increasing reading disappointment, that I grudgingly began to admit the truth: I don’t particularly care for fantasy per se. What I actually cherish is something far more rare: the elevated prose poetry, mythopoeic subcreation, and thematic richness that only the best fantasy achieves, and that echoes in important particulars the myths and fables of old.

This realization eliminates, at a stroke, virtually everything written under the banner of fantasy today.

The mere trappings of the genre do nothing for me when wedded to the now-ubiquitous interminable soap-opera plots (a conservative friend of mine once accurately derided “fat fantasy” cycles such as Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time as “Lord of the Rings 90210″). Nor do they impress me in the least when placed into the hands of writers clearly bored with the classic mythic undertones of the genre, and who try to shake things up with what can best be described as postmodern blasphemies against our mythic heritage.

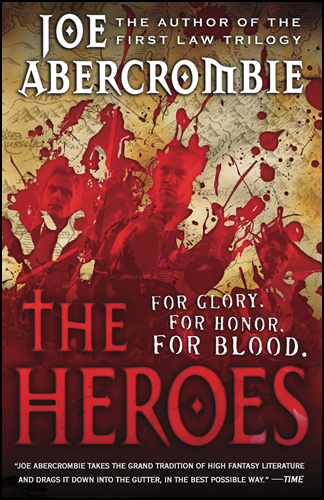

Take the latest novel by popular Brit author Joe Abercrombie (b. 1974), who regularly hits the UK bestseller lists with his self-described “edgy yet humorous un-heroic fantasy.” Titled The Heroes, the tome is guaranteed, given the scribe’s past work, to feature the exact opposite of what it advertises. “Abercrombie takes the grand tradition of high fantasy, and drags it down into the gutter, in the best possible way,” gushed Time magazine about Best Served Cold, his previous book.

Alas, I haven’t read it — Abercrombie’s freshman effort, the massive First Law trilogy (The Blade Itself, Before They Were Hanged, and Last Argument of Kings) was more than enough for me. Endless scenes of torture, treachery and bloodshed drenched in scatology and profanity concluded with a resolution worthy of M. Night Shyamalan at his worst, one that did its best to hurt, disappoint, and dishearten any lover of myths and their timeless truths. Think of a Lord of the Rings where, after stringing you along for thousands of pages, all of the hobbits end up dying of cancer contracted by their proximity to the Ring, Aragorn is revealed to be a buffoonish puppet-king of no honor and false might, and Gandalf no sooner celebrates the defeat of Sauron than he executes a long-held plot to become the new Dark Lord of Middle-earth, and you have some idea of what to expect should you descend into Abercrombie’s jaded literary sewer.

On various blogs you can find critics raving about this mythic bait-and-switch. “Gritty, violent, morally ambiguous and darkly funny fantasy with a streak of intelligent cynicism,” says Adam Whitehead of The Wertzone. “Dark, almost nihilistic, yet shot through with black humour,” writes Simon Appleby at Book Geeks, adding approvingly that, “[Abercrombie] writes about ordinary people thrust in to extraordinary situations who seldom, if ever, acquit themselves heroically.”

Troll the Amazon reviews of many of the latest books hailed as among the great mold-breaking fantasies of the last few decades, and you’ll see similar memes cropping up again and again. One fan reviewing Matthew Woodring Stover’s otherwise ingeniously plotted Caine books bemoans, as I did when trudging through them, the main character’s continuous “bitter, cynical and almost self-hating monologue.” Most of the second book in the series has Caine paralyzed and gracing the reader with detailed descriptions like, “I am — right now, lying naked in a pool of a dead woman’s shit, chained to stone, gangrene eating my dead-meat legs….”

The latest entry in Steven Erikson’s ten-volume Malazan Book of the Fallen, a series running many thousands of pages, is described by one exhausted fan as “pointlessly depressing. . . a lot of death that seems purely random and serving no purpose at all.” “Despair and fatalism dominate,” confirms another reader. (For those who haven’t gotten enough, Erikson recently announced that, with the help of another writer, he will now be expanding his opus from ten volumes to twenty-two — assuming both he and his fans live that long.)

Michael Swanwick’s subversive 1993 novel The Iron Dragon’s Daughter sported a title that lured in many young girls thinking they were getting a standard Young Adult fantasy. According to Publisher’s Weekly (and confirmed by my torturous slog through it a few years ago), it was actually a “nihilistic tale features a human changeling who tries to make her way in a cutthroat society that mirrors contemporary life. . . a powerful, yet dark and hopeless fantasy that should forever shatter charming illusions of Faerie and its folk.” Scenes of teenybopper elf sex and coke-snorting pile one atop the other until the book becomes to fantasy literature what the films of Larry Clark (Kids, Bully) are to cinema.

To be sure, people have every right to publish such books, and in so doing express their frustration or boredom with what can loosely be called the classic Tolkien/Howard mode. Such blowback against the grandmasters of fantasy is nothing new — it stretches back at least to 1934, when a teenaged Robert Bloch (who later went on to write Psycho) wrote in the letter column of the pulp magazine Weird Tales that:

I am awfully tired of poor old Conan the Cluck, who for the past fifteen issues has every month slain a new wizard, tackled a new monster, come to a violent and sudden end that was averted (incredibly enough!) in just the nick of time, and won a new girlfriend, each of whose penchant for nudism won her a place of honor, either on the cover or on the inner illustration. Such has been Conan’s history, and from the realms of the Kushites to the lands of Aquilonia, from the shores of the Shemites to the palaces of Dyme-Novell-Bolonia, I cry: “Enough of this brute and his iron-thewed sword-thrusts — may he be sent to Valhalla to cut out paper dolls.”

But, to quote Tolkien’s famous rejoinder to his critics from his introduction to the revised edition of The Lord of the Rings, “Some who have read the book, or at any rate have reviewed it, have found it boring, absurd, or contemptible; and I have no cause to complain, since I have similar opinions of their works, or of the kinds of writing that they evidently prefer.” The other side thinks that their stuff is, at long last, turning the genre into something more original, thoughtful, and ultimately palatable to intelligent, mature audiences. They and their fans are welcome to that opinion. For my part — and I think Tolkien and Howard would have heartily agreed — I think they’ve done little more than become cheap purveyors of civilizational graffiti.

Soiling the building blocks and well-known tropes of our treasured modern myths is no different than other artists taking a crucifix and dipping it in urine, covering it in ants, or smearing it with feces. In the end, it’s just another small, pathetic chapter in the decades-long slide of Western civilization into suicidal self-loathing. It’s a well-worn road: bored middle-class creatives (almost all of them college-educated liberals) living lives devoid of any greater purpose inevitably reach out for anything deemed sacred by the conservatives populating any artistic field. They co-opt the language, the plots, the characters, the cliches, the marketing, and proceed to deconstruct it all like a mad doctor performing an autopsy. Then, using cynicism, profanity, scatology, dark humor, and nihilism, they put it back together into a Frankenstein’s monster designed to shock, outrage, offend, and dishearten.

In the case of the fantasy genre, the result is a mockery and defilement of the mythopoeic splendor that true artists like Tolkien and Howard willed into being with their life’s blood. Honor is replaced with debasement, romance with filth, glory with defeat, and hope with despair. Edgy? Nah, just punk kids farting in class and getting some giggles from the other mouth-breathers.

It’s quite rich to see many of the guys writing fantasy today being praised for (to once again quote Publisher’s Weekly talking about Joe Abercrombie) successfully exposing the “madness, passion, and horror of war.” How soon we forget that some of the early work of J.R.R. Tolkien — the man who pioneered the selfsame High Fantasy now being dragged “down into the gutter” to make it suitably “edgy” — was penned while he sat in the trenches of World War I, even while most his closest friends were being killed. Tolkien later wrote the a sizable amount of The Lord of the Rings during the Second World War, while worrying about two of his sons as they headed off to do their part.

Call me humorless, call me old-fashioned, but I daresay the good professor had a much better idea of war and heroes than the nihilistic jokesters writing modern fantasy.

To be continued. . . . .

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.