Up-by-his-bootstraps lawyer and would-be political candidate J.D. Vance has an answer to the academic economists who argue amnesties will not harm Americans’ wages and wealth.

“One of the things I had no idea about, coming from a working-class background, is that America’s ruling class loves to celebrate how much power and money it has,” Vance wrote in a March 18 Newsweek op-ed:

I call these “masters of the universe” events, and they’re held all over the country in fancy hotels, ski lodges and beach resorts. On this particular evening, my wife and I found ourselves at a roundtable with the CEO of a large hotel chain on our left, and a large communications conglomerate on our right.

The Republicans, we’re often told, are the party of the rich and famous. Yet nearly everyone assembled at this dinner simply loathed Donald Trump. He was the focus of nearly every conversations. And then the hotel CEO announced, “Trump has no idea how much his policies are hurting business. I mean, we can’t keep people for $18 an hour in our hotels. If we’re not paying $20, we’re understaffed. And it’s all because of Donald Trump’s immigration policies.”

Let’s pause for a second to appreciate one of the wealthiest men in the world complaining about paying hard-working staff $20 an hour. The only thing he was missing was the Monopoly Man hat and cane. His argument, while vile, was at least intellectually honest: “Normally, if we can’t find workers at a given wage, we just get a bunch of immigrants to do the job. It’s easy. But there are so few people coming in across the border, so we just have to pay the people here more.” This is why the American labor movement opposed immigration expansion for much of the past century—until recently, when many labor unions decided that being woke took priority over protecting workers.

Vance followed up with a March 18 tweet, saying, “We have a border crisis because Democratic donors love cheap labor.”

Vance’s story about wages is timely because business groups are pushing amnesty bills amid a barrage of PR that suggests amnesties are no threat to the wages of ordinary Americans.

For example, Mark Zuckerberg’s FWD.us advocacy group posted a multipage letter on February 12 by numerous economists who argued that Americans would gain from the flow of cheap, migrant labor.

The February 11 letter by academic and activist economics started with the obvious “Prior research by the U.S. Department of Labor and independent academic analyses demonstrate that granting legal status raises the wages of beneficiaries.”

But the letter also claimed that other economists believe amnesty makes Americans’ wages go up:

A White House Council of Economic Advisers analysis of DAPA [President Barack Obama’s 2014 Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents quasi-amnesty] and other reports authored by economists … concluded that beyond the wage gains of program beneficiaries, legalization would increase the average wages of all Americans.

The letter’s claim of evidence for American wage gains rests on a thin, weak, and skewed base: A 2014 report by President Obama’s economic advisers — which concluded, “deferred action for low-priority [lower skilled] individuals would increase the wages of all native workers by 0.1 percent on average by 2024.” — plus two reports by the pro-migration Center for American Progress (CAP).

In turn, the two CAP reports rest on a few papers by a handful of pro-migration economists, chiefly “Gianmarco I.P. Ottaviano and Giovanni Peri.”

But in a March 2020 interview on BBC, Peri acknowledged reduced immigration helps to raise Americans’ wages. The BBC interviewer asked, “It may lead to wage growth, but this could be an overall economic problem for the United States?” Peri answered, “Indeed, indeed,” before arguing higher wages would curb companies’ ability to launch new projects.

The February 11 economists also argued amnestied migrants would enlarge the economy, raise total payroll for all U.S. workers, and boost tax revenues for governments. But those claims say nothing about average wages for individuals Americans.

“It’s like arguing that a town with 100 people is much richer when 50 new people move in because the economy is bigger,” responded Steven Camarota, the research director at the Center for Immigration Studies. “The original 100 people [may not] get any richer because a bigger economy doesn’t [automatically] mean that people make higher wages,” he told Breitbart News.

“If it did, Bangladesh would be considered a more wealthy country than New Zealand,” he added.

The February 11 economists also say amnesties will restore valuable workplace protections for Americans.

Those workplace conditions and rights have been damaged by employers hiring many illegal aliens, the economists admitted. But the proposed amnesties contain no safeguards against future illegal migration, so Vance’s story shows how employers will continue to undermine workplace rights by hiring waves of illegal aliens.

In fact, President Joe Biden’s main amnesty proposal would expand the inflow of blue-collar and white-collar foreign workers and would include no new curbs against the inflow of additional illegal aliens.

Representatives for FWD.us and for the lead author of the February 11 letter, Eileen Applebaum, declined to answer questions for Breitbart News.

Other pro-migration groups bombard legislators with claims amnesties and migration boost the economy — as if a bigger economy automatically translates into more wages for their voters. For example, Douglas Holtz-Eakin is president of the American Action Forum. He posted a March 9 op-ed at TheHill.com, arguing, “immigrants generally add to job creation and wage growth in the United States.”

A legal brief by economists for a 2015 lawsuit in Texas also touted gains for migrants, saying, “These benefits include increasing the ability of workers, immigrant and native alike, to access worker protections … there is little reason to predict countervailing economic harm to native-born workers and U.S. businesses.”

Sometimes, the academic economists who are recruited for these pro-amnesty letters sometimes include admissions that work against the lobbyists’ claims. Mike Bloomberg’s New American Economy group produced a 2017 letter from “1,470 economists” touting the economic benefits of immigration. But a close read of the 2017 letter shows the economists admitted wage losses:

Immigration undoubtedly has economic costs as well, particularly for Americans in certain industries and Americans with lower levels of educational attainment. But the benefits that immigration brings to society far outweigh their costs [to those Americans].

But this barrage of credentialed PR does have an impact on media coverage: Few editors or reporters cover the economic impact of legal or illegal migration, despite its central impact on their readers’ and viewers’ wages, training, and housing prices.

Instead, many elite editors and reporters avoid dramatic fights over migration and money and prefer to showcase the interests of migrants.

“Research shows that immigrants strengthen the economy and typically don’t compete with U.S.-born workers for jobs or lower their wages,” says the August 2020 article in the Los Angeles Times by Molly O’Toole. She won the media industry’s Pulitzer award in 2020 for sympathetically covering migrants who were kept out of the United States and its labor market.

Three New York Times reporters, led by White House reporter Michael Shear, wrote on April 2020:

While numerous studies have concluded that immigration has an overall positive effect on the American work force and wages for workers, Mr. Trump ignored that research on Tuesday, insisting that American citizens who had lost their jobs in recent weeks should not have to compete with foreigners when the economy reopens.

Shear and his two peers linked to just one paper by one author to justify their claim. But the linked pro-migration author admitted in her 2018 paper that “research suggests that an increase in the share of low-skilled immigrants in the labor force decreases the price of immigrant-intensive services, such as housekeeping and gardening, primarily by decreasing wages among immigrants.”

Similarly, a three-byline article in Politico about President Biden’s immigration strategy ignored the economics. Biden’s deputies “want to change the very way Americans view migration.” The authors, Laura Barrón-López, Sarah Ferris, and Christopher Cadelago, even ignored the billions of dollars in remittances that migrants send home to support their families — even though that money is also used by corrupt governments to avoid political and economic reform. The article also avoids the U.S. side of the extraction-migration equation, even though many U.S. companies and donors gain from the induced inflow of poor workers and consumers.

In the fight over migration and wages, “it is extremely common for politicians, opinion writers, and reporters to claim ‘virtually all’ economists agree that immigration creates only winners, not losers,” Camarota wrote in a spring 2021 report for the National Association of Scholars. “There are some economists who say things like that, but that is not what the research shows … It is simply wrong to argue that economic research shows immigration has no negative effect on workers.”

Breitbart News asked Camarota to explain this widespread skew in reporting. “The people who lose [wages from immigration] tend to be younger, less educated, and less skilled,” he responded. “In other circumstances, we are often very concerned about that population because we recognize that they are already the poorest, the least likely to work, and haven’t seen very little wage increases in recent decades … But when the topic turns to immigration, we’re not supposed to worry about it.”

Breitbart News has reported many statements from CEOs and business groups saying that the federal policy of inflating the new labor supply with legal and illegal migrants does help to cut Americans’ wages.

For example, on page 171 of its September 2016 report, a pro-migration panel picked by the government-backed National Academies acknowledged “immigration imposes a tax on Americans” wages: “Immigrant labor accounts for 16.5 percent of the total number of hours worked in the United States, which … implies that the current stock of immigrants lowered [Americans’] wages by 5.2 percent.”

The admissions also come from independent academics, the National Academies of Science, the Congressional Budget Office, executives, The Economist, more academics, the New York Times, the New York Times again, state officials, unions, more business executives, lobbyists, the Wall Street Journal, federal economists, Goldman Sachs, oil drillers, the Bank of Ireland, Wall Street analysts, fired professionals, legislators, more economists, the CEO of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, 2015 Bernie Sanders, the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board, construction workers, New York Times subscribers, a former Treasury secretary, a New York Times columnist, a Bloomberg columnist, author Barack Obama, President Barack Obama, and the Business Roundtable.

Even the Wall Street Journal admitted in 2016:

Congress has failed to reach a compromise policy on immigration to address employer needs for a steady, legal workforce.

On the ground in the U.S., many employers report the worker shortage is driving up wages, which is good news for low-skilled workers. It is also driving up costs, however, which could hamper investment and fuel inflation.

Much of the academic debate over migration and wages get dragged into micro-economic arguments about wages in Florida during the 1980s. But there is much macro-economic evidence for wage damage, said Camarota:

The main concern there that people often cite is long-term, the productivity gains seem to have all gone to owners of capital … [as]you would expect if immigration is transferring bargaining power from workers to business owners. That’s one piece of evidence. A related piece of evidence is the general lack of wage growth in real terms for most workers …

Wages for people with incomes halfway between top and bottom grew a total of just 8.8 percent from 1979 to 2019, according to a December 2020 report by the Congressional Research Service.

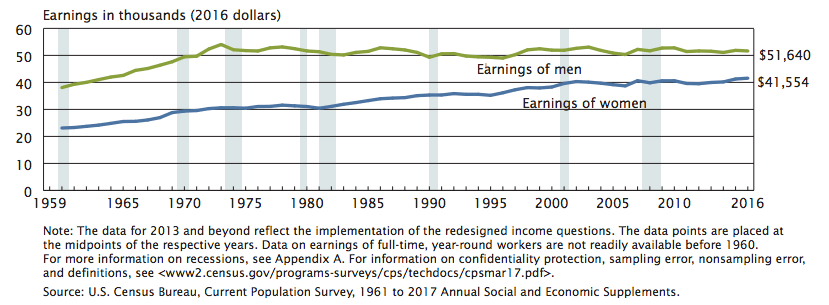

Median earnings of full-time, year-round workers, 15 years and older, 1960 to 2016.

Also, immigration drives up housing costs, cutting the disposable income in Americans’ pockets, especially for lower-income Californians. For example, retail workers must stay on the job for 94 hours per month to pay rent in California, according to Business.org. In low-migration West Virginia, retail workers can pay their rent with 43 hours of work. Similarly, nurses work 24 hours to pay their rent in West Virginia but 30 hours in California.

Some investors — such as Napster founder and FWD.us founder Sean Parker — are hoping to use immigration to drive up housing costs.

Migration also shifts investment and wealth from many interior states to a few coastal states. The shift happens because most investors live on the coasts, and they prefer to put their investment close to home. They face little pressure to put investments into the interior states because the government flies new white-collar and blue-collar immigrants into the coastal worksites each day. From 1995 to 2016, “the Bay Area actually increased its share of venture capital investment from 22 percent in 1995 to 46 percent in 2015 …. [New York] grew from just 3 percent in 1995 to more than 12 percent,” Bloomberg.org reported.

Camarota continued:

The third piece of evidence at a macro level is more of a question of political economy: Why do employers advocate for [more immigrant] workers so much? Whether you’re talking about farmers or owners or billionaire owners of a software company, or everything in between, they’re all advocating for immigration in the belief that it holds down wages for them. Their behavior is inexplicable if immigration doesn’t hold down wages.

For example, the February 11 letter was touted by FWD.us, which is playing a leading role in pushing for a 2021 amnesty.

Former President Donald Trump’s policies provided real-world evidence that reduced migration helps to raise the wages, working conditions, and the workplace authority of Americans.

In 2020, for example, the Census Bureau reported that median household wages rose by seven percent during 2019, following decades of minimal gains. A September 2020 report by the Federal Reserve concluded that the family median income level of high school graduates rose by six percent in 2019.

The amnesty bills being pushed by the investors at FWD.us do not include any useful measure to protect Americans, blue-collar or white-collar, from the next wave of illegal migrants, legal immigrants, or visa workers. In fact, the bill would help the business groups to import many white-collar workers for the jobs sought by the future American students of the pro-amnesty academics.

For years, a wide variety of pollsters have shown deep and broad opposition to labor migration and the inflow of temporary contract workers into jobs sought by young U.S. graduates.

The multiracial, cross-sex, non-racist, class-based, intra-Democratic, and solidarity-themed opposition to labor migration coexists with generally favorable personal feelings toward legal immigrants and toward immigration in theory — despite the media magnification of many skewed polls and articles that still push the 1950’s corporate “Nation of Immigrants” claim.

The deep public opposition is built on the widespread recognition that migration moves money away from most Americans.

It moves money from employees to employers, from families to investors, from young to old, from children to their parents, from homebuyers to real estate investors, and from the central states to the coastal states.

The economists who signed the February 11 letter were described as:

Eileen Appelbaum, Co-Director, Center for Economic and Policy Research

Leah Boustan, Professor of Economics, Princeton University

Clair Brown, Professor; Director, Center for Work, Technology and Society, UC Berkeley

Paul Brown, Professor of Health Economics, UC Merced

Brian Callaci, Postdoctoral Scholar and Economist, Data & Society Research Institute

Stephanie L. Canizales, Assistant Professor of Sociology, UC Merced

Katharine Donato, Donald G. Herzberg Professor of International Migration, and Director of the

Institute for the Study of International Migration, Georgetown University

Indivar Dutta-Gupta, Co-Executive Director, Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality

David Dyssegaard Kallick, Director of Immigration Research Initiative, Fiscal Policy Institute

Charlie Eaton, Assistant Professor of Sociology, UC Merced

Ryan D. Edwards, Associate Adjunct Professor, Health Economist and Demographer, UCSF

Edward Orozco Flores, Associate Professor of Sociology, UC Merced

Jason Furman, Professor of Practice, Harvard University

Fabio Ghironi, Paul F. Glaser Professor of Economics, University of Washington

Shannon Gleeson, Associate Professor, Department of Labor Relations, Law, and History,

Cornell University, School of Industrial and Labor Relations

Clark Goldenrod, Deputy Director, Minnesota Budget Project

Laura Goren, Research Director, The Commonwealth Institute for Fiscal Analysis

Matt Hall, Associate Professor of Policy Analysis & Management, Cornell University; Director,

Cornell Population Center

Stephen Herzenberg, Executive Director, Keystone Research Center

Gilda Z. Jacobs, President & CEO, Michigan League for Public Policy

Sarah Jacobson, Associate Professor of Economics, Williams College

Vineeta Kapahi, Policy Analyst, New Jersey Policy Perspective

Haider A. Khan, John Evans Distinguished University Professor; Professor of Economics,

University of Denver

Sadaf Knight, CEO, Florida Policy Institute

Sherrie Kossoudji, Associate Professor, Ret., The University of Michigan

Adriana Kugler, Professor of Public Policy and Economics, Georgetown University

Charles Levenstein, Professor Emeritus of Work Environment Policy, UMass Lowell

Margaret Levenstein, Research Professor; Director, Inter-university Consortium for Political

and Social Research, University of Michigan

Laurel Lucia, Health Care Program Director, UC Berkeley Labor Center

Robert G. Lynch, Young Ja Lim Professor of Economics, Washington College

Rakeen Mabud, PhD, Director of Research and Strategy, TIME’S UP Foundation

Gabriel Mathy, Assistant Professor of Economics, American University

Darryl McLeod, Associate Professor of Economics, Fordham University

Joseph McMurray, Associate Professor of Economics, Brigham Young University

Edwin Melendez, Professor of Urban Policy and Planning, Hunter College-CUNY

May Mgbolu, Assistant Director of Policy and Advocacy, Arizona Center for Economic Progress

Ruth Milkman, Distinguished Professor, CUNY Graduate Center; Former President, American

Sociological Association

Tracy Mott, Professor of Economics, Ret., University of Denver

Francesc Ortega, Dina Axelrad Perry Professor in Economics, Queens College of the City

University of New York

Ana Padilla, Executive Director, Community and Labor Center, UC Merced

María del Rosario Palacios, Executive Director, GA Familias Unidas

Lenore Palladino, Assistant Professor of Economics & Public Policy, University of

Massachusetts Amherst

Manuel Pastor, Director, Equity Research Institute, University of Southern California

Mark Paul, Assistant Professor of Economics, New College of Florida

Giovanni Peri, Professor of Economics, UC Davis

Diana Polson, Senior Policy Analyst, Pennsylvania Budget and Policy Center

Steven Raphael, UC Berkeley Professor and James D. Marver Chair in Public Policy, Goldman

School of Public Policy

Martha W. Rees, Professor Emerita of Anthropology, Agnes Scott College

Juliet Schor, Professor of Sociology, Boston College

Heidi Shierholz, Senior Economist and Director of Policy, Economic Policy Institute

Taifa Smith Butler, President & CEO, Georgia Budget & Policy Institute

Dr. Ashley Spalding, Research Director, Kentucky Center for Economic Policy

Anna Stansbury, Economics PhD Candidate; PhD Scholar in the Program in Inequality and

Social Policy, Harvard University

Marc Stier, Director, PA Budget and Policy Center

Edward Telles, Distinguished Professor of Sociology; Director, Center for Research on

International Migration, UC Irvine

Esther Turcios, Legislative Policy Manager, Colorado Fiscal Institute

Eric Verhoogen, Professor of Economics and of International and Public Affairs; Co-Director,

Center for Development Economics and Policy, Columbia University

Christian Weller, Professor of Public Policy, University of Massachusetts Boston

Meg Wiehe, Deputy Executive Director, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy

Barbara Wolfe, Richard A. Easterlin Emerita Professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Yavuz Yasar, Associate Professor of Economics, University of Denver

Marjorie S. Zatz, Professor of Sociology, UC Merced

Naomi Zewde, Assistant Professor of Public Health, City University of New York

The economists who signed the submission for the 2015 lawsuit were described as:

Jared Bernstein is an economist in Washington, DC. From 2009 to 2011, he was the Economic Adviser to Vice President Joe Biden, executive director of the White House Task Force on the Middle Class, and a member of President Obama’s economic team. Prior to that, he served in the Labor Department during the Clinton Administration.

Leah Boustan is an Associate Professor of Economics at the University of California, Los Angeles, and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Katharine M. Donato is a Professor of Sociology at Vanderbilt University. Shannon Gleeson, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Labor Relations, Law, and History at the School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University.

Matthew Hall is an Associate Professor of Policy Analysis and Management at Cornell University. His research includes a focus on the incorporation of low-skill and unauthorized immigrants into the United States labor and housing markets.

David Kallick is a Senior Fellow at the Fiscal Policy Institute, where he directs the Immigration Research Initiative.

Adriana Kugler is a Professor of Public Policy at Georgetown University.

Robert Lynch is a Professor of Economics at Washington College.

Douglas Massey is the Henry G. Bryant Professor of Sociology and Public Affairs at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University.

Manuel Pastor is a Professor of Sociology and American Studies & Ethnicity at the University of Southern California.

Steven Raphael is a Professor of Public Policy at the Goldman School of Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley.

Audrey Singer is a Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.