When Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida and Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts agree on anything, that’s news in and of itself. After all, Rubio’s most recent legislative rating by the left-leaning Americans for Democratic Action is zero, while Warren’s is 100 percent.

So when the two opposite lawmakers agree on something important, that’s big news. Thus it’s noteworthy that both Rubio and Warren support the idea of “Economic Patriotism”—that is, the conscious boosting of American jobs and the American economy. As such, they are both repudiating the old idea that what matters most is the free working of the global market, in which jobs could end up anywhere in the world, wherever international capital calculates to be the best place.

To be sure, Rubio and Warren are plenty different; let’s take a closer look at where they agree, and where they differ.

Elizabeth Warren’s Economic Patriotism

On June 4, Warren, who announced her presidential candidacy last year, released “A Plan For Economic Patriotism.” In that document, she declares her love for this country, and yet, she jabs, “The giant ‘American’ corporations who control our economy don’t seem to feel the same way. They certainly don’t act like it.”

Continuing in that caustic vein, Warren adds, “Sure, these companies wave the flag — but they have no loyalty or allegiance to America.” She then name-checks a number of big corporations, including Levi’s and General Electric, that have moved jobs overseas.

To address this problem, as well as others, Warren itemizes a string of policy proposals, starting with a pledge of “aggressively using all of our tools to defend and create American jobs.” Okay, that’s a familiar enough sentiment; moreover, some of her specifics might seem like mere bureaucratic box-shuffling, as when she suggests creating a new “Department of Economic Development,” replacing the Commerce Department and folding in other agencies, such as the Small Business Administration and the Patent and Trademark Office.

Yet other Warren ideas seem more promising, as when she argues for increased federal funding for R&D and then, at the same time, mandating that production stemming from such R&D be done in the U.S. Now that’s Economic Patriotism: If American taxpayers pay for the idea, then American workers ought to be hired to bring that idea into production.

Of course, Warren’s forward-thinking stance is not without risk. Most obviously, in her focus on American jobs, she is repudiating at least some of the legacy of the last two Democrat presidents, who were happy enough to see American jobs go elsewhere, in keeping with their globalist vision.

Indeed, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama both seemed to think of themselves as internationalists, not nationalists; they often seemed most enthused about trade deals, immigration initiatives, and foreign military interventions.

Clinton, for example, passed NAFTA, encouraged immigration, and intervened everywhere from Haiti to Bosnia. And in his post-presidency, he founded the Clinton Global Initiative. As for Obama, he was given to saying things like, “The burdens of global citizenship continue to bind us together.” (Of course, the Republican president in between those two, George W. Bush, was also a globalist; he was even more eager about invading the world, as well as inviting the world.)

On June 4, the left-wing HuffPost described Warren’s new trade stance as something decidedly different from previous policy: “Warren is making a crystal-clear statement of principles, and an equally plain break with the past 30 years of American trade policy.” That is, she is breaking with all of the ’90s, the ’00s, and the ’10s.

It remains to be seen whether or not Democrat primary voters will go along with Warren’s repudiation of their party’s recent past. In fact, polls show Warren running no better than third in the 2020 presidential primaries; her standing of around eight percent is less than a quarter of Joe Biden’s. And Biden, of course, is the ultimate nostalgia candidate; if you loved the ’90s, ’00s, and ’10s, then Biden is the obvious pick because he supported all the key globalist policies of the era. In fact, he still does: Remarkably, even in 2019, Biden has dismissed any concerns about the economic (or strategic) threat from China.

Yet interestingly, in the meantime, Warren has received support—or at least an admiring shout-out—from Fox News star Tucker Carlson; on June 5, Carlson lauded the Bay Stater’s focus on American jobs; as he put it, “She sounds like Donald Trump at his best.”

It’s worth emphasizing that Carlson did not endorse Warren; he cited many other important issues—including abortion and guns—where he disagreed with her and the rest of the Democrat establishment. In fact, Carlson obviously hopes that the Republican Party will preempt Warren with its own message of Economic Patriotism—maybe starting with … the senior senator from Florida.

Marco Rubio’s Economic Patriotism

On June 6, Rubio, a former—and perhaps future—presidential candidate, published a sharp response to his Yankee colleague: “Warren’s ‘economic patriotism’ plan [is] simply not possible with a progressive agenda.”

As the Floridian put it, “In the 21st century, we need a new policy that can build the competitive businesses of the future and create high-wage American jobs.” And yet, he continued, “America’s radical progressive movement is incompatible with an agenda that truly confronts the challenges of our time, such as the rise of China and decline of working-class economic stability.”

In other words, Rubio is agreeing with Warren on the value of “economic patriotism” as a goal but disagreeing on the precise policies to get us to a better place.

Rubio’s core argument is that Warren’s Economic Patriotism is undermined by her leftism. As he put it, “Progressivism requires that today’s Democratic Party mistake cultural fights and upper-middle-class material interest for real productivity. This error reveals itself by leaving out or opposing all sorts of policies that would benefit American workers.”

Then Rubio listed some highlights of his plan, including, “Economic Patriotism should limit low-skilled immigration”; “Economic Patriotism should recognize that environmental regulations come at the cost of manufacturing jobs”; “Economic Patriotism should support President Trump’s trade actions against China”; “Economic Patriotism should promote alternate paths to higher education for working-class students”; and “Economic Patriotism requires a strong national defense.” Thus we can see: There might be rhetorical overlap with Warren, but there’s plenty of substantive difference.

Still, Rubio joins with Warren in offering a bleak assessment of the last three decades of economic policymaking, under both Republicans and Democrats:

America’s decline on the economic value-chain is not inevitable. It is not due to external forces like automation or globalization, but to our own policy decisions as a nation, which have often prioritized financial over real investment, digital over physical innovation, and foreign over domestic labor.

In fact, Rubio has thought deeply about the restoration of U.S. economic primacy; as I noted in February, Rubio’s report on the Chinese economic threat—“Made in China 2025 and the Future of American Industry”—offers both compelling reading and a worthy checklist of action items.

The Rubio-Warren Convergence

Okay, so both Warren and Rubio use the same phrase, Economic Patriotism. And for all their stated differences, they agree on a key symptom of the problem, outsourcing, which is deleterious to both employment and national security. The Economic Policy Institute, for instance, has estimated that in the dozen years after the U.S. normalized trade relations with China in 2000, some 3.2 million American jobs went to the People’s Republic.

Yet still, as noted, the two lawmakers have been on opposite sides for just about every specific legislative question; in 2017, for instance, Rubio was an “aye” for President Trump’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, while Warren was a “nay.”

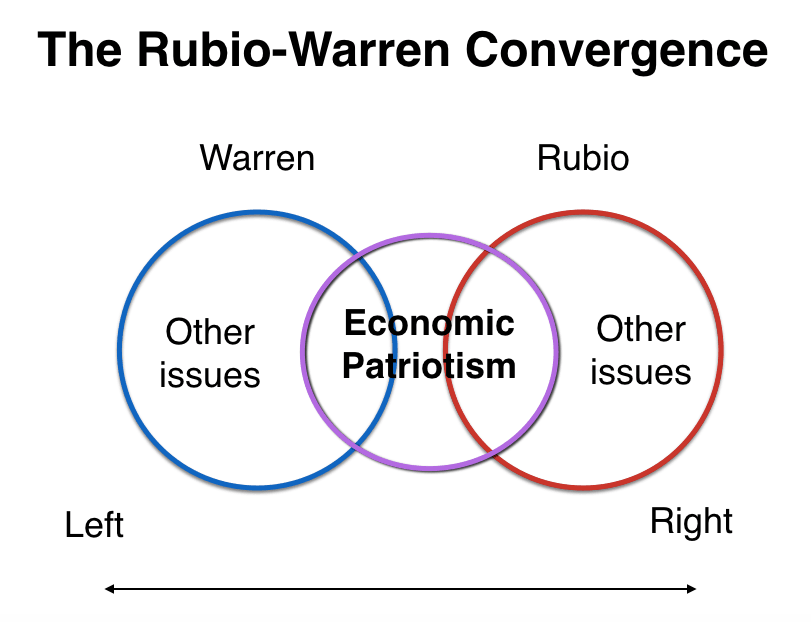

So again, where, exactly, do Rubio and Warren agree? Where do they disagree? Perhaps this graphic, below, will help clarify the convergence, as well the divergence:

From the above graphic, we can see that on most matters, the two leaders are far apart—and they both probably like it that way. Thus the blue circle (Warren) and the red circle (Rubio) are far apart; yet still, their shared vision of Economic Patriotism fits into that middle purple circle—and that’s the commonality between Rubio and Warren.

This is the tantalizing prospect of Economic Patriotism: that the two parties—or at least some of their leaders and some of their voters—might come together on meat-and-potatoes issues.

Of course, any possible convergence between the two parties is not limited to just Rubio and Warren. As far back as 2016, Breitbart News’ Matthew Boyle was speculating on the possibility that many Donald Trump voters, and many Bernie Sanders voters, shared a populist economic impulse.

Admittedly, the last three years have mostly been a misfire in terms of realizing that hope, and yet the spark of potential is still there, even as the torch seems to have passed to Rubio and Warren, as well as others, such as, say, Missouri’s Republican Sen. Josh Hawley and Ohio’s Democrat Sen. Sherrod Brown. And then there’s Tucker Carlson, not a politician—even if some would like him to be one—serving as a sort of bridge across the partisan divide.

The Meat and Potatoes of Economic Patriotism

As we have seen, the beefy center of Economic Patriotism is industry and industrial jobs; it is, after all, economically, psychologically, and militarily healthy for a country to produce things.

So in that spirit, Economic Patriots declare it to be national policy that vital wares be Made in U.S.A. As I have written many times—including as recently as June 6, on the anniversary of D-Day—America can’t be safe and strong without home-grown industrial and technological muscle.

Of course, Democrats might not see it that way; most Democrats, after all, seek to cut military spending, and seem little interested in such America First ideas as missile defense.

Instead, today’s Democrats would rather spend less on defense and spend more—a lot more—on environmental concerns, especially their cherished Green New Deal. For instance, Gov. Jay Inslee of Washington State, a rival to Warren for the ’20 Democrat nomination, has unveiled a Green New Deal plan that would spend, or allocate, $9 trillion.

Most Republicans scoff at such ideas, and yet the Green New Deal is taking shape, and one of these days, the Democrats will be in a position to start enacting it.

Yet in the meantime, it’s interesting to observe how the Green New Deal is changing; it’s becoming less of a vision of mandated scarcity and more of a vision of boosted technological advance.

Yes, the Green New Deal is getting heavier on R&D, focusing increasingly on batteries, improvements in renewable energy sources, and, crucially, carbon capture for fossil fuels. In fact, many Republicans, too, are embracing carbon capture, if only as a way of making sure that some future Democrat government doesn’t shut down Texas and North Dakota.

(Needless to say, Joe Biden has been accused of plagiarizing his carbon-capture plan, and yet, Biden’s ethics aside, such overlap with GOP thinking is the essence of convergence.)

Moreover, speaking of R&D and industry, it’s interesting that many Green New Dealers express a fond recollection for great American feats of the past, including not only getting out of the Depression, but also winning World War II and putting a man on the moon.

So we can see: As green thinking moves along, there’s less emphasis on less and more emphasis on more. That is, the original green goal of neo-medieval “hobbitzation”—as in, peasants living in holes in the ground, Lord of the Rings-style, while the noble lords are enjoying their castles—is being displaced by an emphasis on 21st-century industrialization. As Warren herself said on June 4, the way forward on the environment is to “invest in science, in innovation, and American workers—that’s how we’re going to do it!”

Still, many Republicans will dismiss all of this as out of hand, dubbing it a green boondoggle. Yet still, it seems prudent for the GOP to have some sort of response to the climate-change issue at the ready; as they say, You can’t beat something with nothing.

The point here is not to argue the science of climate change, or “climate change.” Instead, it’s to observe that Economic Patriots should focus on technologies that can create good jobs at good wages—wherever they are to be found.

In that spirit, Rep. Matt Gaetz, the Trump-loving GOP congressman from Florida, has jumped into the debate, offering his own tech-heavy, job-rich, “Green Real Deal.” Indeed, with Republican input, a Green New Deal could turn into a bonanza for rural- and small-town America.

Of course, there are other issues, too, that Economic Patriots might wish to rally around. One such issue is the much-discussed big infrastructure program, which everybody seems to like—and which nobody, it seems, can get done.

For all their differences, Rubio and Warren have done something important: They have jointly raised the flag of Economic Patriotism. So now we’ll have to see where they end up, and also, which other leaders step forward to claim this valuable centrist turf. After all, it’s hard to think of a better platform than American jobs, for American workers, as part of an overall vision of a prosperous and strong America.

As we wait, we can probably agree that Carlson nailed it on June 5, when he said that the candidate who best champions Economic Patriotism “would be elected in a landslide. Every. Single. Time.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.