Geopolitical Futures’ annual forecast predicts the maturation of the microchip-based productivity cycle means that the economic challenges facing America’s middle- and lower-class “can’t be solved.”

GF’s George Friedman comments that in absolute terms, U.S. productivity saw its first decline in over a decade in 2016. He sees that declining productivity as the beginning of a global shift that means the economic expansion that began 1982, with the expanding use and availability of microchips, is now in an irreversible structural decline.

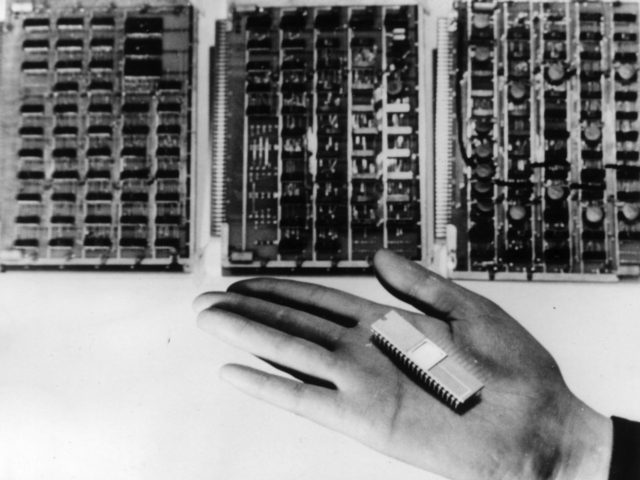

The U.S. began a cycle of rapid productivity growth starting in the early 1970s, when the microchip entered the consumer and commercial markets. The initial disruption was led by the introduction of a hand-held calculator called the “Bowmar Brain,” as well as the Casio watch. Those were followed in 1975 by MITS Altair 8800 as the first personal computer.

That means the microchip industry’s commercial history is nearing 50 years old — about the same age as Ford was in 1953, after being founded in 1903. According to Friedman: “The automobile was a mature product by then, with some minor innovations still to come, but with the primary focus on styling and marketing.”

Detroit’s “Big Three” in 1953 were at “culturally the high point of automobiles, when new models were accompanied by great excitement.” But the automobile was becoming a commodity. Higher quality and lower cost German and Japanese vehicles surged into the American market over the net two decades. The federal government had to bail out Chrysler as the upper midwest became the “Rust Belt.”

Microchip technology revolutionized industrial, administrative and government functions by increasing productivity across all levels of the economy. But productivity increases were heavily concentrated on an individual basis, not across all workers.

Microchip technology motivated financial restructuring to eliminate large numbers of low-skilled workers. High-skilled workers that leveraged the technology commanded high wages, but marginalized less-skilled workers had to settle for lower-wages or watch their jobs be exported to low-wage countries.

The actual decline in U.S. productivity in 2016 is what Friedman calls, “the pivot toward a new reality.” Microchip-based technology is no longer “cutting edge,” and the revolutionary impact of software applications are old news. The focus for personal computing devices is now on styling and minor innovations. New applications still excite the consumer, as cars did in 1953, but the level of innovation has peaked and productivity is headed down.

Friedman expects this “pivot” will gain global traction in 2017, although most observers will claim that the productivity slow-down is due to “forces specific to 2017.” Just as it took about 7 years before the public realized in 1982 that the productivity boom was happening, global productivity growth has been declining since 2008 and the public still hasn’t grasped the significance of the trend change.

Now that we have entered a period similar to 1955-1970, the early signs of microchip technology maturation can be seen in the “decline of Microsoft (which was once an innovator) and the collapse of Hewlett-Packard, as well as the new, and predictable, difficulty Apple is having maintaining profit levels.”

Microchip technology will remain a central industry, and some new ancillary industries will be spawned, but 2017 could be the beginning of an irreversible long-term decline in productivity growth. That will restrain growth and increase the negative wage impact on the middle and lower-middle classes.

Most industries could be reduced to looking desperately for new and more dubious consumer applications, like “Apple Pay” and “Apple Watch.” Even the wages of most Silicon Valley software engineers, who were the biggest winners in the last three decades, will fall like other middle class workers as microchip-based innovation withers.

The Wall Street Journal has reported that “America’s tech giants are broadening their sights from the digital to the physical world in a bid to expand their influence, and their bottom lines. They promise to reinvent everything from cars to thermostats to contact lenses.”

Friedman does agree that between now and 2030, “there will be an overlap with a new technology that is not yet obvious, and that will revolutionize life the way the internal combustion engine and the microchip did.” But if that overlap emerges in the next 10 years, it will take another 15 years before it has a meaningful impact on the economy.

Between now and 2030, Geopolitical Futures expects the worldwide productivity crisis will intensify.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.