Editor’s Note: This Op-Ed was written and submitted to Breitbart Texas by Kathleen Hunker, senior policy analyst for the Center for Economic Freedom at the Texas Public Policy Foundation.

Constitution Day might as well be called America’s forgotten holiday, or so joshed a colleague of mine in the office elevator. There was a lilt of exaggeration in his voice, but he was not too far off the mark.

In an age of saturated media, where any feel-good invention is celebrated with wall-to-wall Facebook coverage, Constitution Day often struggles to warrant a measly share. Certain schools provide educational programming in order to qualify for federal funds. But overall, the anniversary has not pierced the culture’s firewall. It subsists as a ceremonial observance only, and a dowdy one at that.

For conservatives, the popular apathy stings a little more this year. Congress has proven unable or unwilling to forecheck the Administration’s offensives on the Constitution. The country’s other mitigating bodies have proven no more effective. The malaise gives the impression that the nation has washed its hands of the Founders’ work. If that’s the case, then the flaw does not reside in the Constitution as written, but the government’s slow assumption of responsibility of “positive rights” (aka economic entitlements) it can never fully provide.

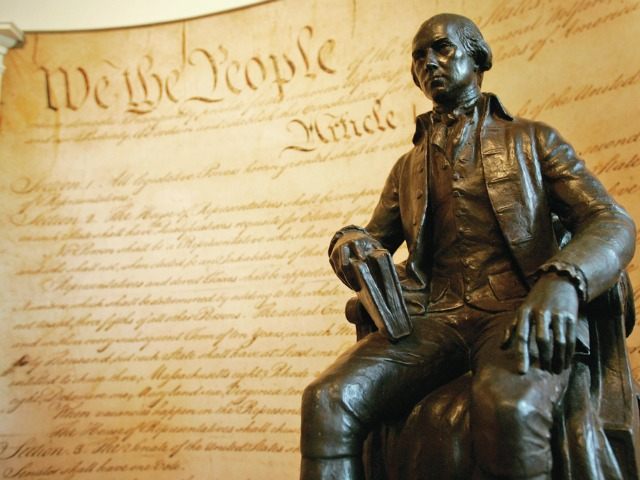

Popular apathy aside, Constitution Day marks a great historical achievement not seen before or since. On this day in 1787, after months of intense debate, negotiation, and compromise, a delegation housed in Philadelphia signed the final draft of what would become the core of the U.S. Constitution. While the document would not be ratified until the following June, and even then only with the promise of a Bill of Rights, the structure it put in place has endured.

Indeed, the United States now boasts the oldest surviving written constitution among nations. Evolutions in political fashion have stretched both its letter and spirit. For the most part though, the Constitution remains this country’s center of gravity, around which all political activity revolves. What Alexis de Tocqueville called the “great experiment” has been a success.

That legacy has been ignored of late. Our cultural gatekeepers prefer to emphasize instead where the Constitution allegedly has struggled.

This is particularly true among the Left, which has long bemoaned the Constitution’s preoccupation with “negative rights” (rights that don’t necessarily appropriate others’ money, such a free speech) and enumerated powers, and has a habit of idolizing the charters of other nations which incorporate broader guarantees.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg offers a famous example. During an interview with Al-Hayat TV, she advised Egyptians that if she were in charge of drafting their new constitution, she would not look to the United States. Instead, she would rely on “all the constitution-writing that has gone on since the end of World War II.” South Africa for instance was “a great piece of work” and made “a deliberate attempt to have a fundamental instrument of government that embraced basic human rights.”

Her comments are telling. After Apartheid, South Africa had adopted a throng of socio-economic rights to help those wronged by the systematic discrimination of the previous regime. This included a claim to adequate housing, healthcare, social security, as well as a requirement that the government minimize economic inequality.

The virtues of the U.S. Constitution were not lost on Justice Ginsburg. She did drop a couple of praises by the end, most notably about the First Amendment. The aroma of a modern social democracy, however, with an explicit mandate to fix society’s ills simply proved too sweet a treat to pass over without remark. Never mind that the modesty of the U.S. Constitution is what allowed it to endure for so long—more on that in a moment.

If there’s a problem with the U.S. Constitution today, it’s that the document was so triumphant that Americans forget the genius of its design. Every election cycle we cast votes with the expectation that should a new party win, not only will there be a peaceful transition of power, but that the incoming party will be confined by the rule of law. Ronald Reagan rightly reminded us in his First Inaugural that this achievement “is nothing less than a miracle.”

National constitutions abroad have lasted on average seventeen years since 1789. The U.S. Constitution meanwhile has weathered two world wars, along with the rise of fascism and communism. It guided westward expansion, governs the largest GDP in the world, and has emerged from every crisis, from slavery to terrorism, with a reaffirmation of its founding principles.

Academic literature has no shortage of explanations on why this is. The most common accounts cite the Founder’s decision to divide power as well as their accurate perception of human nature, neither of which I contest. What Americans today overlook is that the institutions themselves are not sufficient.

Paper barriers can corral the occasional rogue if designed correctly. They cannot turn aside a stampede of public actors seeking richer pastures beyond the fence line. If the barriers are to hold, then the words on the document must have such meaning that the average official will approach, only to turn away under their own volition. The citizenry has to believe in those limits and accept them as hallowed.

Let’s look again at South Africa. The commentators who defended Justice Ginsburg’s interview all but admitted that the country’s socio-economic rights are aspirational. They can only be realized by sensible legislation and ample wealth—resources which are not always in ready supply. South Africa’s purported advantage, these commentators quibble, resides in the fact that the positive claims give citizens legal recourse to demand government action.

In other words, the South African government is in perpetual violation of their country’s constitution, but that’s okay because citizens can get a declaration telling the government to try harder.

What I want to know is how does a country, especially a new democracy, cultivate an ethos of diligent vigilance when the government’s duty under the constitution is only ever half-done. How do you keep the people’s resignation towards poor results from filtering down to other, more fundamental rights? By what standard do you judge the government’s success?

The American Founders made a deliberate decision not to promise its citizens anything outside of the government’s control for these very reasons. The government instead refrains from interfering in the affairs of its citizens and lets them seek socio-economic comforts on the market.

Frédéric Bastiat reflected if you “proclaim that all benefits and misfortunes flow from [the law] . . . you will open the floodgates to an unending flow of complaints, hatred, unrest, and revolution.” Once it is accepted that the government is responsible for individual happiness, then each and every disappointment will chip away at the trust citizens have in the principles that underpin the law. The sanctity of constitutional rights erodes, and the pressure on public officials to perform their duties within the proper confines lightens.

Conservatives celebrate Constitution Day fearful that the institutions built by the Founders are starting to give way. They might be right. But attempts to fortify those institutions will fail unless conservatives roll back the assumption that the government is a source of economic security and comfort. Employing government as the source of happiness distorts the way Americans view the Constitution, so that its principles become unattainable goals rather than objective truths instantly deserving of respect.

Checks and balances defend liberty. Good citizenship and a faith in the rule of law helps ensure that there is nothing to defend against.

Kathleen Hunker is a senior policy analyst with the Center for Economic Freedom at the Texas Public Policy Foundation. Follow her on Twitter @KathleenHunker.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.