Editor’s Note: During the siege of the Alamo in 1836, a convention of delegates met in the town of Washington, near Brenham, and selected five men to quickly draft a Declaration of Independence. On March 2, 1836 the assembled convention unanimously approved the document. Below, former Texas Land Commissioner Jerry Patterson introduces an article by Dr. Stephen L. Hardin, a history professor from Victoria College, titled “March 2, 1836: The Myth and Meaning of Texas Independence.”

I think I know a great deal about Texas, and I’ve penned several columns about the unique and inspiring history of my great state. Recently, while doing research on Texas Independence day for another narrative, I found a column written almost two decades ago by a historian and college professor named Stephen L. Hardin. Dr Hardin not only knows his history and writes well, he’s a rare commodity among college professors-he’s a conservative who has extreme dislike for political correctness.

I share this with you in the true spirit of independence. God Bless Texas

Jerry Patterson

March 2, 1836:

The Myth and Meaning of Texas Independence

By Dr. Stephen L. Hardin

Professor of History

The Victoria College

Victoria, Texas

March 2, 1836 dawned, frigid and gray; cutting winds blew through glassless windows. Texians – as they styled themselves – huddled close, pulled blankets tight, and gave birth to a dream. At the Town of Washington, fifty-nine representatives voted into existence a sovereign nation: the Republic of Texas. Tennessean George C. Childress had drafted the independence document. In word and spirit it borrowed heavily from Thomas Jefferson” original 1776 declaration. No matter. Anglo-Celtic Texians proudly embraced the values and traditions of their founding fathers. “The same blood that animated the hearts of our ancestors in ’76 still flows in our veins,”one frontier preacher affirmed. Still, not all the delegates were of that blood. Four Mexican residents signed the declaration on behalf of their Tejano constituents. By their presence and with their signatures, they demonstrated that they too shared Jefferson’s values – and his vision of liberty. Thus began a decade of independence singular in the annals of American history.

The ramshackle surroundings seemed neither appropriate, nor especially auspicious. The Convention met in an unfinished building lacking glass in the windows or even doors. In lieu of glass, delegates tacked rags tight across the windows. They could have saved themselves the trouble. On March 1, as the members gathered in the Town of Washington, a blue norther swept in. By the morning of the second, the thermometer had plummeted to a brisk thirty-three degrees as gusts whistled through fluttering window cloth.

If the Washington “Convention Center” proved bleak, so too did the rest of the rustic frontier settlement. It did not make a favorable impression upon Virginia native Colonel William Fairfax Gray. He may have tasted sour grapes, for he had earlier applied for the job of convention secretary. Although he did not receive the post, he nevertheless maintained a record of the proceedings in his diary. In numerous instances, Gray’s account is more complete than the official minutes. Still, he found the Town of Washington a “disgusting place.” Cold, uncomfortable, and unappreciated, Gray described Washington in wholly uncharitable terms:

It is laid out in the woods, about a dozen wretched cabins or shanties constitute the city; not one decent house in it, and only one well-defined street, which consists of an opening cut out of the woods. The stumps still standing. A rare place to hold a national convention in. They will have to leave it promptly to avoid starvation.

Even here in Texas most folks still remain unclear about the meaning of that cold March day in 1836. Myth and misunderstanding also obscure the event. Many believe, for example, that the delegates signed the Texas Declaration on March 2. Not true. The delegates read and approved the document on that day, but remember that they did not have a photocopier at their disposal. Clerks worked through the night. Perforce, the five hand-written copies were not ready for signatures until the following day. Nor did all sign even then. Seven delegates had not yet arrived on March 3. As they dragged in, the latecomers added their names for a total of fifty-nine signatories. Nowadays Texans remember the small hamlet where the delegates gathered as Washington-on-the-Brazos. Nobody called it that in 1836. Texians back then simply called it the “Town of Washington.” Not until later would ‘Washington-on-the-Brazos” come into common usage.

Whether one observes March 2 or March 3, one constant remains; the delegates could not have picked a worse time to declare independence. To many contemporary observers, such confidence appeared reckless. As delegates brazenly declared Texas independent, the artillery of Mexican dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna hammered the walls of the Alamo. Just four days later his troops would assault the crumbling fort and wipe out every rebel defender. At the same time, General José Urrea’s division swept northward through the coastal prairies. He would subsequently capture the entire rebel command of Colonel James W. Fannin, Jr. following the Battle of Coleto on March 19. Acting upon Santa Anna’s orders, Mexican troops executed Fannin and the majority of his Goliad garrison, some 342 men. The twin defeats at San Antonio and Goliad generated panic among Texian settlers who fled toward the Louisiana border. The “Runaway Scrape” they called it. To declare independence amid all this chaos seemed more than unduly hopeful. Indeed, to most it resembled a fool’s errand.

On April 21, General Sam Houston’s vengeful army swept the Mexican camp at San Jacinto and the skeptics recanted. On that momentous afternoon, enraged Texians slaughtered 650 Mexican soldados and took another 700 prisoner. Most important, the following day Texians captured President-General Santa Anna. At San Jacinto Texians won a great victory, but only with the capture of the Mexican dictator did the battle become decisive.

Sandwiched between the defeat at the Alamo and the victory at San Jacinto, it is not all that startling that the importance of March 2 gets lost in the glare of those two shining episodes. The date is not a state holiday; public schools do not let out; newscasters rarely recall the event.

Even in 1836, Texians did not consider the approval of Childress’s declaration a momentous occasion. Nearly all the representatives had arrived in Washington knowing that independence was a forgone conclusion. Gray captured the lackadaisical nature of the proceedings in his diary, but was so underwhelmed that he could not manage to spell Childress’s name correctly. The important news of the day, at least as far as Gray was concerned, was the break in the weather: “The morning clear and cold, but the cold somewhat moderated.” Only then, did he mention – in an offhand manner – that the Convention had approved the declaration of independence:

The Convention met pursuant to adjournment. Mr. Childers [sic], from the committee, reported a Declaration of Independence, which he read in this place. It was received by the house, committed to a committee of the whole, reported without amendment, and unanimously adopted, in less than one hour from its first and only reading. It underwent on discipline, and no attempt was made to amend it. The only speech made upon it was a somewhat declamatory address in committee to the whole by General Houston.

And it was done. At the end of the day, the delegates merely rubber-stamped a question that they had already decided.

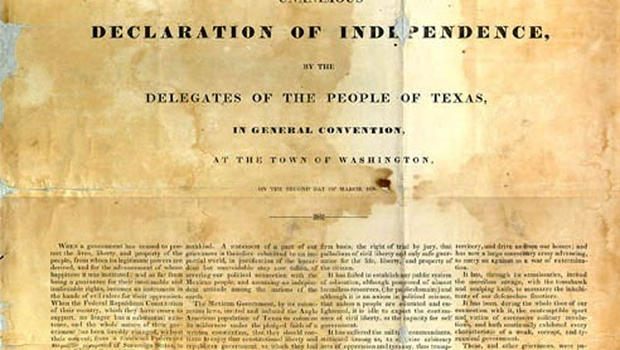

So apathetic were the delegates concerning the document–or, perhaps, so chaotic were conditions–that all five of the original hand-written copies went missing. In 1896 an original copy turned up in the files of the U.S. State Department. It appears that Texas agent William H. Wharton deposited his copy there in 1836. As Commissioner of the Texas Republic, he had traveled to Washington, D. C. to inquire about admitting Texas into the Union. If annexation proved impossible, he then was to push for the recognition of Texas as an independent nation. He must have submitted one of the original copies to support the claim that Texas was, in fact, an independent nation and not merely a breakaway province within the Mexican Republic. State Department officials returned the precious document to Texas. Today this it resides deep inside a vault at the State Library in Austin. A reproduction of this copy is on permanent display at the state capitol. The archivists, having lost it for so long, are not willing to take chances with the only surviving original.

So here we are near the end of the twentieth century. What do the events of 163 years ago have to do with us? What does it all mean? Of late the delegates have not fared too well at the pens of activist historians. They see Texas independence as the action of ungrateful snits that willfully ignored Mexican generosity. Typical of this new breed is Colorado writer Jeff Long. In his book Duel of Eagles: The Mexican and U.S. Fight for the Alamo, he sides with the Mexicans.

It was grotesque that a host of squatters, land speculators, and short-term colonists should expect the Mexican government to grant them government conducted in the English language. Mexico had not forced the Anglo-Americans to come to Texas. Mexico had certainly not promised those who did come “that they should continue to enjoy that constitutional liberty and republican government to which they had been habituated in the land of their birth, the United States of America.” To the contrary, those settlers in Texas who were legitimate had pledged themselves to a set of regulations extended by a whole new authority.”

Like many of his ilk, Long has a reductionist understanding of Texas history. To be sure Mexicans were astoundingly generous to norteamericano colonists. A head of a household normally received a league and a labor. That amounted to a whopping 4,605 acres. Additionally, immigrants could also expect a tax rebate until they got on their feet in their adopted homeland. Americans who had been ruined in the Panic of 1819 flocked to Mexican Texas by the thousands. And they were grateful to Mexico for the chance–and a place–to make a fresh start. To most American immigrants, it seemed as if Mexico offered more opportunity than the “land of opportunity” itself. Still – and this is the part Mr. Long conveniently remembers to forget – most Texians immigrated under the Mexican Constitution of 1824. Under that covenant Mexican citizens enjoyed a republican form of government and most of the power of government resided at the state and local levels. Indeed, the Mexican federalists were great admirers of the United States Constitution of 1787 and employed it as a model for their 1824 charter. When Santa Anna revoked the Constitution of 1824 and declared himself dictator in 1835, all bets were off. American Mexicans considered themselves bound to the old constitution and were not about to sit still and be quiet while a military dictator appropriated the reins of government. They were not, however, alone it that. Many Federalistias –Mexicans loyal to the Constitution of 1824 – also took up arms to resist Santa Anna’s centralist regime.

So the revolt that began near Gonzales in October 2, 1835, was a civil war – not a bid for complete separation from Mexico. Both Anglo-Celtic Texians and the native Tejanos fought for self-government within the federalist system created by the Constitution of 1824. The war was not, as some have insisted, a “culture conflict.” Indeed, many Texas Mexicans joined with norteamericano neighbors to resist the centralistas.

Having said that, why did Texians overwhelmingly support complete separation from Mexico only five months later? Is Long correct? Was the Texas Revolution merely a shameless land grab? Once again, the answer is more involved than some allow themselves to believe. Texians were disappointed when Federalists from the interior did not rush to Texas to take up the struggle. Texian leaders had tried to squash any mention of independence, fearing that such remarks might alienate Mexican federalists. By February 1836, however, a majority of Texians had concluded that they could expect no help from that quarter. Why had the federalists south of the Rio Grande been so unwilling to support the Texian federalists? The short answer is that they simply did not trust the Anglo-Americans.

Mexican federalists had plenty of reasons to mistrust their northern neighbors. They recalled the two decades from 1800 to 1820 as the era of the filibusters. Throughout that period, American soldiers of fortune such as Philip Nolan, Augustus Magee, and James Long (apparently no relation to the Colorado revisionist) had attempted to wrest Texas away from Spain. Mexicans declared their independence from Spain in 1821, but many still remembered the filibusters and mistrusted Americans. Mexican Secretary of State Lucas Alamán expressed such concern succinctly. “Where others send invading armies,” he groused, “[the Americans] send their colonists.” He understood that American newspapermen wrote incendiary articles calling for the occupation of Texas. He knew that in 1829 President Andrew Jackson had dispatched the brutish Anthony Butler to Mexico with an offer to buy Texas. He was also aware that Americans almost constantly spoke of the “reannexation of Texas,” a crack-brained belief that Texas should have been a part of the Louisiana Purchase owing to the short lived La Salle colony of 1685. Little wonder then that Mexican federalist viewed the colossus to the north and its wayfaring citizens as a threat to Mexican nationhood.

Texas leaders came to understand that alone they could not win the war. If Mexican federalists would not lend a hand, they must enlist assistance from the United States. War is the most expensive of all human endeavors. While Texians claimed thousands of acres of disposable land, they were cash poor. To win this war they first had to fight it. But that required troops, weapons, and provender and all those items cost money – lots of it! They were not so naïve as to believe that President Jackson would risk an international incident by openly supporting the Texas rebels against Mexico. They did, however, hope to enlist the support of individual Americans who believed in their cause. The ad interim government dispatched Stephen F. Austin–the most famous Texian–as an agent to the United States. Once back in the “old states” the empresario appealed to citizens to provide volunteers, funds, and supplies for Texas. He and other Texas agents visited American banks to secure loans for the Texas war effort.

That is where they consistently encountered problems. Banks in the north would not even consider supporting with their money a cause that might ultimately bring another slave state into the union. Southern bankers, while more sympathetic, would not lend their money so long as the war remained a domestic Mexican squabble. They let Austin and the other agents know, however, that they might be interested if – and only if, Texians declared their complete separation from Mexico.

Why this southern support for Texas independence? Southerners anticipated that an independent Texas would remain independent for, say, three or for months, before entering the union as a slave state. In 1836 the United States had an equal number of free and slave states. Since both free and slave states voted as a block, it created a legislative gridlock with neither side being able to gain advantage. Southerners believed that adding Texas to the list of slave states would tilt the congressional balance of power in their favor.

Austin may have been lukewarm concerning slavery, but he was a firebrand in the cause of Texas. In a rambling letter dated January 7, 1836, he neatly summed up the situation.

I go for Independence for I have no doubt we shall get aid, as much as we need and perhaps more – and what is of equal importance – the information from Mexico up to late in December says that the Federal party has united with Santa Anna against us, owing to what has already been said and done in Texas in favor of Independence so that our present position under the constitution of 1824, does us no good with the Federalists, and is doing us harm in this country, by keeping away the kind of men we most need[.] [W]ere I in the convention[,] I would urge an immediate declaration of Independence – unless there be some news from the [Mexican] interior that changed the face of things – and even then, it would require very strong reasons to prevent me from the course I now recommend.

When Stephen Fuller Austin spoke, Texians listened. By March 2, nearly all of them believed that their best hopes for the future rested on complete separation from Mexico.

How did Tejanos regard the independence announcement? The fighting had severely tested the loyalty of Texas-born Mexicans, most of whom resisted the inexorable movement toward independence. While many were willing to fight, even die, for the Constitution of 1824, they were understandably hesitant to support an open break with their mother country. The politically astute among them realized that in an independent Texas they would be woefully outnumbered by norteamericanos and thus relegated to minority status in a land dominated by foreigners who possessed little knowledge of or appreciation for their distinctive culture.

The war cast Tejanos into a whirlpool of changing politics and shifting loyalties. Wealthy landowners like José Antonio Navarro, Erasmo Seguín, and Plácido Benavides had been early proponents of American emigration. They were willing to abet slavery to promote the cotton trade and economic growth for the province. Having placed their economic and political bets on their new allies, when open revolt erupted federalist Tejanos could only try to play out their hand.

Independence forced Tejanos to make hard choices. Some like Navarro and the Seguíns opted to support the new republic. But others like Benevides, the alcalde of Victoria, could not force their principles to bend that far. Benevides was a Mexican first, a federalist second. He had seen much hard fighting at the siege and storming of Béxar in 1835, but when he heard of the March 2 declaration he went to Goliad commander James W. Fannin and informed him he was leaving the army. He could not abide centralist despotism, but neither could he be a party to striping Mexico of Tejas. He believed his only honorable option was to return to his ranch and sit out the war as a non-combatant. Fannin understood his plight and sent him home with his blessing. Still other Tejanos, like Carlos de la Garza, Juan Moya, and Agustín Moya, resented the influx of foreign settlers, view opposition as disloyalty to their motherland, and flocked to the centralist banner. These were not men who wet their fingers to test the prevailing winds; they did not plot their course according to the latest public opinion poll. They were deeply rooted in principle and tradition. Each of these Texas Mexicans followed his heart and while the path did not always lead to victory, it never led to dishonor.

That was then; this is now. Why should modern Texans observe the events of 163 years ago? Why should they stop for a moment every March 2 to reflect on the meaning of Texas Independence Day?

The first reason is historical – this day marks the creation of the Republic of Texas. For almost a decade Texas existed as a sovereign nation. It exchanged foreign ministers with other countries; it had a national army and navy (though neither was especially effective); it maintained a national currency (though, to be sure, the money was never worth much). When Texas joined the Union in 1845, it did so as a nation and thus demanded rights not accorded to mere territories. By order of Joint Resolution of the U.S. Congress, Texas retained possession of its public lands. So large was the landmass of Texas, the same resolution allowed Texas to divide into as many a five states. In 1850 Texans did, in fact, sell a portion part their western holdings to pay off the debt incurred during the Republic period. Since then, however, they have been reluctant to part with even so much as an inch of their sacred soil – the resolution notwithstanding. Texas nationalism has proved stronger that political expediency.

The second reason is psychological, perhaps even spiritual. The Republic of Texas was an ephemeral empire. Like the spring bluebonnets, it bloomed, blossomed, and blanched with the sands of time. But also like the state flower, its scent lingers in the hearts and imaginations of every Texan. A moment ago I referred to Texas nationalism. Many outside the state would, no doubt, find that remarkably pretentious, but those who live here understand the truth of it. Texas existed as a nation for ten years; Texans got used to the idea; and nationalism is a difficult habit to break. The novelist John Steinbeck perhaps said it best:

Texas is a state of mind. Texas is an obsession. Above all, Texas is a nation in every sense of the word.

March 2 is a day to celebrate Texas distinctiveness. Now I’m not saying that Texans are better that other folks, but I am saying that we’re different. And if a people consider themselves different, they are. March 2 should be to Texans what St. Patrick’s Day is to the Irish. But what if you are a Tejano. Should you want to celebrate the day that Texas separated itself from Mexico. You bet! Even as early as 1835 Tejanos were distinctive from other Mexicans. The ranching culture that developed in Texas produced its own clothing, its own music, its own customs, and its own food. Gringos call it “Mexican food,” but all one has to do to put the lie to that assertion is to eat the food in the interior – or try to. It is rather bland and not nearly as good as the Tejano food (we might as well call it what it really is) right here at home. We sometimes call it Tex-Mex, but in truth, it’s all Tex and precious little Mex. It is found nowhere else on earth. How many things might we say that of? Tejano music is not Mexican; it is not American. It is Texan and is found nowhere else on earth. Tejanos also speak a variety of Spanish called Tex-Mex. But try using it in Mexico City, or worse yet, in Seville. Again, it is a unique language and is found nowhere else on earth. Truth is if you’re a Texan – be you brown, black, white, yellow, or red – you don’t rightly belong anywhere else. Steinbeck nailed that too. “A Texan outside of Texas is a foreigner,” he observed. That applies to Tejanos as much as, probably more than, other Texans. After all, whose family has lived here the longest?

Even today it is common to hear natives claim to be “Texans first, Americans second.” It is impossible to believe that they would feel that way had the Texas Republic never existed. There in Washington on that cold, windy day in March of 1836, delegates, both Anglo and Tejano, shouted to the world that they were different. Not Mexican were they, not American, but something else. They were, they insisted, TEXIANS. They gave birth not only to a dream, but also to a mystique. Not all Texians wanted to join the Union in 1845. Early settler, ranger, and Indian fighter, Robert Hall spoke for many of the old breed. “I was opposed to annexation,” he groused, “and voted first, last, and all time for the Lone Star.” The degree of Texas nationalism may be a matter of debate, but it is perhaps significant, that even when they joined the Union, the old Texians could not bear to part with their cherished flag. And even today, the banner of nation continues to swell over the Lone Star State.

This article by Professor Hardin was re-published with permission of the author. Dr. Hardin is a professor of history at Victoria College. He is also the author of “The Texian Iliad.” The article was written several years ago. Time related references are correct as of the original publication date.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.