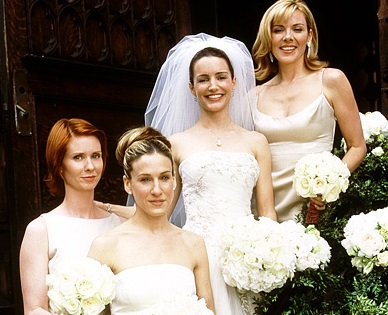

As this year marks the 15 year anniversary of “Sex and the City“, the New Yorker’s Emily Nussbaum writes about its legacy.

Even as “The Sopranos” has ascended to TV’s Mt. Olympus, the reputation of “Sex and the City” has shrunk and faded, like some tragic dry-clean-only dress tossed into a decade-long hot cycle. By the show’s fifteen-year anniversary, this year, we fans had trained ourselves to downgrade the show to a “guilty pleasure,” to mock its puns, to get into self-flagellating conversations about those blinkered and blinged-out movies. Whenever a new chick-centric series débuts, there are invidious comparisons: don’t worry, it’s no “Sex and the City,” they say. As if that were a good thing.

What I find interesting about her article, and thus the show, is that I agree with Nussbaum for entirely different reasons. Her positives are my negatives. My positives are her negatives. But our conclusion is the same. She writes:

For a half dozen episodes, Carrie was a happy, curious explorer, out companionably smoking with modellizers. If she’d stayed that way, the show might have been another “Mary Tyler Moore”: a playful, empowering comedy about one woman’s adventures in the big city.

Instead, Carrie fell under the thrall of Mr. Big, the sexy, emotionally withholding forty-three-year-old financier played by Chris Noth. From then on, pleasurable as “Sex and the City” remained, it also felt designed to push back at its audience’s wish for identification, triggering as much anxiety as relief. It switched the romantic comedy’s primal scene, from “Me, too!” to “Am I like her?”

The free-wheeling “have sex like a man” Carrie wasn’t exactly the “me, too!” mirror that the average American woman could relate to [see Ann Coulter’s excellent column on this in How to Talk to a Liberal (If You Must)]. In an early episode, Carrie learned she couldn’t have no-strings-attached sex, yet critics and fans still referred to her that way. Nussbaum noticed:

At first, Miranda and Charlotte were prudes, while Samantha and Carrie were libertines. Unsettlingly, as the show progressed, Carrie began to glide toward caution, away from freedom, out of fear.

Predictably, fans of the “sexual revolution” were not happy with the ending. Nussbaum concludes:

And then, in the final round, “Sex and the City” pulled its punches, and let Big rescue Carrie. It honored the wishes of its heroine, and at least half of the audience, and it gave us a very memorable dress, too. But it also showed a failure of nerve, an inability of the writers to imagine, or to trust themselves to portray, any other kind of ending–happy or not. And I can’t help but wonder: What would the show look like without that finale?

Let’s review where the series left the four characters. Carrie converted the ultimate “modellizer” to a man who would fly half-way around the world for a difficult, non-traditional beauty. Feminist lawyer Miranda realizes she and her out-of-wedlock baby belong with the father and that it’s worth making career sacrifices for the family. Serial slut Samantha allows herself to fall in love and experiences the first mature, secure and fulfilling relationship she’s ever had. Charlotte, the Rules-obsessed WASP, marries a Jew after pouring her heart out to him while asking for nothing in return and they adopt a Chinese baby.

It’s a conservative fairy tale and a feminist nightmare. Even better, Nussbaum acknowledges that this is what at least half the audience wanted to see. Despite years of feminists’ insistence that women are more fulfilled by careers, no one wondered “Did Miranda win that big case?” “Did Charlotte go back to work?” “Did Carrie get her column back after returning from Paris?”

No one cares. Women wanted family to come first, motherhood and husbands for the characters because many of them also want it for themselves. “Sex and the City“ transitioned from a love letter to a Dear John letter to the feminists’ ideals.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.