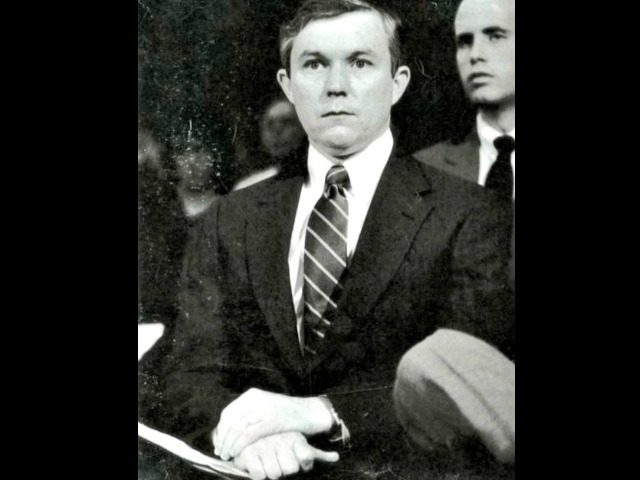

Decades-old racially charged allegations against Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-AL) parroted by the establishment media and a handful of far left Senate Democrats do not hold up under scrutiny, an extensive investigation conducted by Breitbart News has found.

There are essentially three central allegations the left levels against Sessions. The first pertains to his involvement in a 1980s voter fraud case, which, evidence shows, Sessions prosecuted to ensure a fair election for black Democratic citizens of the county. The second involves allegations from a former assistant attorney, who was described by co-workers as a “disaffected” employee with a “bad attitude problem” and whose testimony was vigorously debunked by highly credible witnesses. The third involves accusations from an ex-Department of Justice attorney whose credibility was brought into question after he was forced to recant portions of his testimony, in which he fabricated false allegations against Sessions.

In recent weeks, the populist Senator’s partisan opponents—eager to relive the contentious 1986 confirmation hearings that resulted in Ted Kennedy’s successful “Borking” of Sessions from a federal judgeship before such a term even existed—have dredged up these sensational allegations from their 30-year slumber.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren said in mid-November:

Instead of embracing the bigotry that fueled his campaign rallies, I urge President-elect Trump to reverse his apparent decision to nominate Senator Sessions to be Attorney General of the United States. Thirty years ago, a different Republican Senate rejected Senator Sessions’ nomination to a federal judgeship. In doing so, that Senate affirmed that there can be no compromise with racism; no negotiation with hate. Today, a new Republican Senate must decide whether self-interest and political cowardice will prevent them from once again doing what is right.

Breitbart News, however, went back and read the original 565-page transcript of the 1986 hearing to separate fact from fiction. Upon reviewing the transcript and interviewing individuals with first-hand knowledge of the case, the portrait that emerges is one of a faithful public servant derailed by discredited allegations.

Contrary to the slander peddled first by Kennedy and regurgitated now by Warren, the evidence and testimony from the 1986 hearing depicts a man who cares deeply for the equal and just treatment under the law of all Americans, and who has stood at the vanguard of the various civil rights battles of our times. Sessions, whose favorite book is To Kill a Mockingbird authored by his fellow native Alabamian Harper Lee, was credited during the hearing for helping to obtain the first death penalty conviction of a white man for the murder of a black citizen in Alabama since before World War I.

Throughout the hearing, multiple civil rights leaders testified to Sessions’ dedication and “unequivocal commitment to the prosecution of criminal civil rights cases”— describing him as a prosecutor who went “above and beyond” the call of duty to aid the civil rights division of the Department of Justice at a time when it was not always politically popular to do so in the South.

During the course of the hearing, Judge Cain Kennedy, an African American judge on Alabama’s 13th judicial circuit court, testified to Sessions’ “excellent” reputation in a letter he signed with the other circuit judges. In it he endorsed Sessions and asserted that he was “confident” Sessions “would rule impartially in all matters presented to him” and that the court would be “fortunate” to have someone of Sessions’ stature. Similarly, Larry Thompson, an African American and former U.S. attorney in Atlanta who went on to serve as Deputy U.S. Attorney General under President Bush, described Sessions as a “loyal colleague” and a “good man and an honest man untainted by any form of prejudice.”

Indeed, the contrast between the originally reported allegations and the revelations of the hearing was so stark that the Birmingham News editorial board, which initially called on “Sessions’ sponsors… [to] withdraw his nomination” in March of 1986, eventually reversed its position entirely by May of 1986—urging the Senate to reconsider and “put aside partisan motives” to view Sessions’ “nomination with an open mind.”

Yet despite all of the revelations to come out of the hearings’ proceedings, a new generation of reporters have now taken up their predecessors’ role as chief organ for the same few grave, yet baseless, soundbites proffered by Ted Kennedy and the ghosts of Democrats past.

Sessions’ 1986 confirmation hearing, the Washington Times’ Charlie Hurt writes, was Kennedy’s trial-run for what would become his sabotage just one year later of President Reagan’s Supreme Court nominee, Robert Bork. “Even before they coined a term for it — Borking — they did it to Jeff Sessions, a decent man with a stellar legal reputation,” Hurt wrote. “With only the flimsiest of accusations and innuendos from suspect testimony, Mr. Sessions was duly smeared in the worst way he could imagine.”

“Kennedy took the truth and warped it. He lied,” wrote the state editor of Sessions’ hometown paper, the Mobile Press-Register, in March of 1986.

Against the backdrop of the Sessions attainting led by the late Massachusetts Senator — marred with his own record of moral impropriety spanning from his expulsion from Harvard for cheating to the abandonment of Mary Jo Kopechne to suffocate in an air pocket in his car submerged on Chappaquiddick Island — emerged a formidable foil to Kennedy, who stepped forth as Sessions’ greatest advocate, American war hero, Alabama Senator Jeremiah Denton. The unwavering patriot, who famously outsmarted his North Vietnamese captors to expose how American POWs were being tortured, described the 1986 hearing as a “circus” and characterized the media’s treatment of Sessions as “a tragedy.”

THE PERRY COUNTY VOTER FRAUD CASE

To this day, one of the left’s central allegations against Sessions stems from his involvement in prosecuting a 1985 voter fraud case in which three black defendants were accused of having altered the absentee ballots of black voters in order to thwart the election of black Democratic candidates, whom the defendants opposed, and instead to help hand the election over to candidates the defendants favored.

Because the defendants, most notably, Albert Turner, were civil rights activists, the U.S. attorney’s office — and Sessions, by extension — was accused of having prosecuted the case out of racial motivations.

Sessions’ opponents in corporate media have been quick to pick up on this narrative and have even demonstrated a willingness to obscure inconvenient facts that would undermine it. For instance, USA Today’s Mary Troyan and Brian Lyman wrote an entire article about the Perry County case and the accusations of the prosecution’s racial motivations without once mentioning that both the complainants and the victims in the case were also black Democrats.

Washington Post “fact-checker” Michelle Ye Hee Lee claims to have “read the ~600 page 1986 Jeff Sessions hearing transcript so you don’t have to.” Yet if readers were to rely upon Lee’s synopsis for their information on the case, they would have no knowledge of the significant testimony of LaVon Phillips, a 26-year-old African American legal assistant to the Perry County district attorney with intimate knowledge of the Perry County case who testified on Sessions’ behalf during the 1986 confirmation hearing.

Phillips testified that in the 1980s, black voters in Perry County began “voting more of their convictions, their interests, rather than relying on the, per se, black civil rights leadership.”

“When this happens,” Phillips said, the established “black power base… becomes neutralized” and may object to the loss of power. “This is what is happening in Perry County.”

Phillips explained that in 1982 the Perry County’s district attorney’s office had “received several complaints from incumbent black candidates and black voters that absentee ballot applications were being mailed to citizens’ homes without their request.” Phillips said that their office performed an investigation and sought an indictment against Turner — empaneling a grand jury whose racial makeup was eleven blacks and seven whites.

Phillips additionally testified that, in 1982, Turner was alleged to have engaged in illegal voting activities by picking up absentee ballots, even though he himself ran as a candidate in that election. Phillips testified that Alabama’s criminal code “sternly spells out that no candidate is to solicit, pick up, or even… touch an absentee ballot.” Sessions has separately said that a handwriting expert informed his office that Turner had even written his name on absentee ballots during that election.

While the majority-black grand jury returned no indictments against Turner in the 1982 election, it did find that a fair election was “being denied the citizens of Perry County, both black and white,” and “encourage[d] vigorous prosecutions of all voting laws”— even requesting that an outside agency monitor the election.

After the grand jury issued its findings, the district attorney approached Sessions about taking additional action, but Sessions “literally refused to prosecute the case,” Phillips said. According to Sessions’ testimony, that’s because “it was expected that these problems would not continue after the actions of the Perry County Grand Jury.”

Nevertheless, the problems apparently persisted, and a week before the 1984 primary election, Sessions said he received a call from the district attorney informing him that two black Democratic officials, Reese Billingslea and Warren Kinard, whose candidacies were opposed by Albert Turner, “were very concerned that a concerted effort was being made to deny a fair election” through the use of absentee ballots.

Billingslea wrote a letter on Sessions’ behalf for the 1986 confirmation hearing in which he expressed his appreciation for Sessions’ “professionalism” and role in the investigation.

“I was one of the first black candidates elected in Perry County Alabama,” Billingslea wrote. “During the [1984 primary] campaign I was approached by many of my supporters who informed me… that my opposition had stated publically that they would do anything to get rid of me…. I became convinced that there was concerted, well-organized effort was being made to steal the election from me through the absentee ballot box…. I spoke with him [Sessions] and requested his assistance…. From everything that I was aware, Mr. Sessions and the United States Attorney’s office handled the investigation with the highest professionalism.”

After receiving the call, Sessions took limited action: requesting visual surveillance of the post office building the day before the election.

An examination of the absentee ballots deposited revealed that some had been visibly altered, Sessions said. The altered absentee ballots collected and deposited by Turner had all been “changed in the same manner,” Sessions explained, from “non-Turner-supported candidates to Turner-supported candidates.”

The Sheltons, an African American family in Perry County, were “devastated” to learn their ballots had been changed by Turner without their permission, Phillips said.

Turner apparently even admitted to having changed the Sheltons’ ballots from the candidates they initially voted for to candidates that he favored—claiming that he had their permission to do so. However, the Sheltons ardently denied this, and Sessions noted that it was unlikely they would have given Turner permission since the candidate the Sheltons wanted to vote for, but whom Turner opposed, was their cousin.

However, Sessions explained that despite the evidence, the prosecution was “outgunned” by an impressive team of lawyers representing the defendants (only two lawyers in Sessions’ office had been assigned to the case to face off against the, at one time, 11 lawyers filing motions for the defendants). Testifying on Sessions’ behalf in 1986, William Kimbrough Jr., Sessions’ Democratic predecessor as U.S. attorney, explained that just because a jury returns a verdict against the prosecution does not mean the prosecutor was unjustified in bringing the case forward.

“Quite often, in the South, you do not win civil rights cases. That is not to say they should not be brought,” he explained. “I personally tried a number of civil rights cases involving police brutality or alleged police brutality, and I do not believe I won one of them. I do not apologize to anyone for having brought the case. There was probable cause to believe that somebody’s rights had been abused…. You bring the case because the case needs to brought.”

FIGURES’ ALLEGATIONS

Most of the allegations related to Sessions’ comments on race come primarily from a single source, Thomas Figures, a former assistant U.S. attorney and an African American who worked with Sessions for four years.

Yet, as Sen. Denton noted during the confirmation hearing, “all significant allegations by Mr. Figures have been either refuted or denied—all of them.”

For instance, one of Figures’ most sensational allegations that he “was regularly called boy” by Sessions and others in the office (emphasis added).

Figures’ charge was denied by everyone in the U.S. attorney’s office alleged to have witnessed it. Figures himself, Denton noted, even changed his own story during his testimony—going on to “sheepishly den[y]” his original claim that he was called boy “regularly.”

One of Figures’ proclaimed witnesses, assistant U.S. Attorney Ginny Granade, denied his testimony — as did another colleague, Ed Vulevich.

Vulevich, who had served for 17 years under both Republican and Democratic administrations, testified that Figures suffered from a “persecution complex,” had difficulty “getting along with people” and kept “very much to himself.”

“I might best describe it as the man in a football stadium with 80,000 people but he thinks that when the team huddles, they are all talking about him,” Vulevich said.

The sentiment seemed corroborated by William Kimbrough, Sessions’ Democratic predecessor, who had himself hired Figures. Kimbrough explained that Figures appeared “disaffected” and “had some difficulty” working in a Republican office.

Moreover, although his associations received virtually no media attention, Figures allegedly failed to disclose his ties to individuals who likely harbored ill will against Sessions.

“When Figures testified,” Denton charged, “he failed to disclose his personal and financial interests in the Perry County issue,” namely that the day prior to testifying against Sessions, Figures was hired to defend a disputed election plan in Perry County, which had been drawn up in part by none other than Albert Turner.

Yet perhaps further indicative of Figures’ possible prejudice against Sessions was his allegation involving a joke that Sessions made about the Klu Klux Klan.

The joke was made as Sessions’ office was pursuing the Michael Donald case, in which a black teenager was abducted and murdered by the Klan. Sessions pushed for the case to be tried by the local district attorney rather than the federal government, so that Klansman Henry Hays could be given the death penalty (Hays would not have received the death penalty had the case been tried by the federal government). The successful prosecution ultimately set into motion a series of actions that resulted in financially bankrupting the Klan in Alabama. Democratic Judge McRae credited Sessions as being responsible for getting Hays sentenced to death. “[I] can assure you the State’s conviction of Henry Hays would not have been possible without Jeff Sessions’ assistance,” McRae testified.

This sentiment was echoed by Bobby Eddy, a Democrat and investigator from the Mobile district attorney’s office in the Michael Donald case, who has also been credited with having broken open and solved the 1963 Birmingham church bombing that killed four girls. “Without his [Sessions’] cooperation, the State could not have proceeded against Henry Hays on a capital murder charge,” Eddy testified.

To place this in historical context, Sessions was essentially responsible for helping to make Hays the first white person to be executed in Alabama for the murder of a black citizen since 1913.

While discussing the case with Figures, and by some accounts two Department of Justice civil rights attorneys, Sessions was informed that the prosecution was struggling to collect evidence because some of the Klansmen had been smoking marijuana and were unable recount crucial events. In response, Sessions told the group that he hadn’t known the Klan smoked marijuana and sarcastically joked that he had thought they were okay until he was informed of such.

With the exception of Figures, everyone who heard the joke — including civil rights attorneys Albert Glenn and Barry Kowalski — immediately understood that it was intended humorously.

“I took it wholly as a joke and humor,” Glenn said. “There was no question in my mind at the time that it was meant humorously.”

Barry Kowalski, a self-described lifelong Democrat who would go on to become a famed civil rights attorney and one of the lead prosecutors in the Rodney King trial, testified that he even relayed Sessions’ joke to others “in a humorous vein as well”— something an esteemed civil rights attorney would likely not have done if he had suspected it to have any pretense of racial insensitivity. Kowalski explained that in his mind it was clear “operating room humor” made by a U.S. attorney as he was working to prosecute the Klan.

Yet the media’s reporting on Figures’ allegation has stripped it of all context to distort its meaning and wrongly imply that Sessions respected the Klan. Consider the media coverage below:

“A former coworker testified that Sessions said the Ku Klux Klan was an acceptable organization until he learned that its members used marijuana.” – CNN

“As a U.S. Attorney in Alabama in the 1980s, Sessions said he thought the KKK “were OK until I found out they smoked pot.” – Politico

“[Sessions] famously said of the Ku Klux Klan that he was okay with them, ‘until I learned they smoked pot.’ Sessions later said he was joking.” – Forbes

In reality, the joke actually conveys the exact opposite sentiment: the humor is predicated upon the condition that the joke teller believes the Klan is evil— otherwise the joke doesn’t make any sense. As Sessions explained during the hearing, it would be the equivalent of saying, in jest: “I do not like Pol Pot because he wears alligator shoes.” Even Joe Biden, who attacked Sessions for having made the joke—despite having his own long record of making racially insensitive jokes— acknowledged: “I could see how someone could say that humorously. That [statement] does not mean you are defending the Klan.”

As Sen. Denton observed, if the media were to apply to Figures the same standard of judging a man’s statements without any regard for context as they applied to Sessions, one could equally accuse Figures of having called the NAACP “subversive”—a comment which Figures claims to have made “in jest.”

For his part, LaVon Phillips rejected Figures’ attack against Sessions for joking about the KKK as “ridiculous.” Daniel Bell, the deputy chief of the criminal section of the civil rights division with the Department of Justice, similarly testified that he has never heard Sessions make remarks that he considered to be racially insensitive. “As a matter of fact, my experience with him is that he does not make racial jokes or insensitive jokes,” Bell said.

The sentiment was echoed by State Judge Braxton Kittrell, a Democrat, who sentenced Henry Hays to death. “I have never known him to make racial slurs or remarks,” Kittrell testified. “If he, in fact, had made the remarks which have been attributed to him, I am satisfied that they have been taken out of context, as Jeff Sessions is not that kind of person.”

‘DISGRACE TO HIS RACE’

Perhaps some of the gravest allegations leveled against Sessions come from a J. Gerald Hebert, who during the 1986 hearing was accused of having undermined his own credibility — raising the specter of perjury and defamation — by smearing Sessions with demonstrably false allegations, which he eventually had to admit were “in error.” Hebert now directs the voting rights and redistricting program at the George Soros-funded Campaign Legal Center.

In 1986, Hebert, then a senior trial attorney in the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division who has also reportedly been one of the main redistricting lawyers for the Democratic National Committee, testified that Sessions had called the NAACP and the ACLU “un-American.” Figures testified to having had a similar discussion with Sessions.

When questioned about the allegation, Sessions explained that he was referring to particular positions the groups have taken on foreign policy issues — such as their views on the Nicaraguan Sandinistas. Both then and now, the media have seemed eager to deny this essential context. Sessions “never said he thought that the NAACP or the ACLU were flatly un-American or Communist inspired, yet he has been convicted of it in the media of our land,” Denton observed at the time.

Hebert additionally testified that he once asked Sessions about a judge, who apparently called a white lawyer who handled civil rights cases a “disgrace to his race.” Hebert claimed that when asked about the judge’s comment, Sessions said either, “well, maybe he is” or “well, he probably is” (Byron York notes that Hebert changes his testimony throughout the hearing as to how Sessions responded).

Denton noted that it was Hebert — not Sessions — who, in quoting another, described the white civil rights lawyer as a “disgrace to his race.” Hebert himself never accused Sessions of using the phrase.

Yet while Hebert’s allegations have been parroted ad nauseam in recent media reports, journalists fail to mention that Hebert was forced to recant testimony in which he made up serious, yet demonstrably false allegations against Sessions. Specifically, Hebert falsely testified that Sessions sought to block an FBI civil rights investigation. “Mr. Sessions had gotten in touch with the agents and had called off the investigation,” Hebert claimed. Hebert even said that there had been a conversation with Sessions about the particular investigation in which Sessions “indicated that he did not think the investigation should go forward” — a conversation, which, as it turns out, never actually took place.

A review of the Department of Justice’s record revealed that Hebert’s testimony was not true. Sessions had nothing to do with the investigation because the case arose prior to Sessions’ being U.S. attorney. Yet during his testimony, Hebert “constructed a conversation with Mr. Sessions on that subject… [which] never took place at all,” Denton explained.

“My testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee…. [regarding the FBI voting investigation] was in error. My recollection on this matter has now been refreshed. I have no knowledge that Mr. Sessions ever interfered with any voting investigations in the Southern District of Alabama… I apologize for any inconvenience caused Mr. Sessions or this Committee by my prior testimony,” Hebert said in written testimony.

Interestingly, Hebert “has a history of crying wolf about claims of racial discrimination,” with profound consequences for innocent people, J. Christian Adams told Breitbart.

“Hebert, the leading critic of the appointment of Senator Jeff Sessions as attorney general, has a history of making things up about racial issues— so much so, in fact, that a federal court imposed sanctions in one of Hebert’s voting cases,” Adams recently wrote. “Hebert’s exaggerations about racism in one federal court case [United States v. Jones] resulted in sanctions being imposed by a federal judge, costing the United States taxpayer $86,626.”

In that case, the court chastised Hebert’s team at the Justice Department, writing that it was “unconscionable” that they would “carelessly” hurl “unfounded allegations” of racial discrimination and impugn a person’s good name without any regard for the truth. The court wrote:

A properly conducted investigation would have quickly revealed that there was no basis for the claim that the Defendants were guilty of purposeful discrimination against black voters. Unfortunately, we cannot restore the reputation of the persons wrongfully branded by the United States as public officials who deliberately deprived their fellow citizens of their voting rights. We can only hope that in the future the decision makers in the United States Department of Justice will be more sensitive to the impact on racial harmony that can result from the filing of a claim of purposeful discrimination. The filing of an action charging a person with depriving a fellow citizen of a fundamental constitutional right without conducting a proper investigation of its truth is unconscionable.

A cursory review of recent news coverage shows that more than a dozen reports cite Hebert’s allegations against Sessions without mentioning that Hebert was accused of undermining his own credibility and had to recant fabricated allegations he made against Sessions.

Ryan Reilly of the Huffington Post tried to justify his omission of Hebert’s recanted testimony by characterizing Hebert’s accusation that Sessions blocked an FBI civil rights investigation as a “minor” issue.

“The story stands for itself,” Reilly told Breitbart in an email, referring to his story which prominently featured Hebert’s accusations against Sessions. “That Hebert corrected the record on a minor aspect of his testimony that was based on mistaken recollection does not change the facts laid out in the piece.”

Interestingly, despite opposing Sessions in 1986, Hebert still testified to Sessions’ character and described him as “a man of his word.”

Today, however, apparently emboldened by the passage of time from the original events and the media’s evident refusal to critically examine any of the allegations made against Sessions before printing them, Hebert has adopted a greater flourish for the dramatic in laying out his indictment of Sessions.

Jeff Sessions as attorney general “should make every American shudder,” Hebert wrote in a Washington Post op-ed last month.

In his op-ed, Hebert expressed his need to “once again” add to the public record the now 35-year-old conversation he claims to have had with Sessions. It is unclear from his op-ed, however, why Hebert — now 30 years more senior — thinks the reader ought to believe his recollection of his interactions with Sessions, considering that his recollections had previously been “in error” and needed to be “refreshed.”

‘MOST POPULAR PERSON IN ALABAMA EXCEPT FOR MAYBE NICK SABAN’

While many things are a testament to Sessions’ character, perhaps nothing speaks more than his actions after enduring Kennedy’s 1986 “Borking.”

While most individuals subjected to such a campaign of personal destruction would retreat from public service, Sessions, without complaint and without carrying a grievance, would go on to become the state’s Attorney General and eventually its U.S. Senator.

He succeeded Sen. Howell Heflin, the Alabama Democrat who ultimately voted against Sessions during his 1986 confirmation. When Senator Arlen Specter switched party registration, Sessions ironically replaced the former Republican who voted against him in 1986 as the ranking Republican on the Judiciary Committee. As Congress’s fiercest champion of a pro-American worker agenda that upholds the legacy of late civil rights leader heroine Barbara Jordan, Sessions has squarely taken on what is perhaps the most lasting legacy of his 1986 nemesis, Ted Kennedy: namely Kennedy’s 1965 immigration rewrite that threw open the nation’s floodgates to foreign workers, imperiling civil rights by diminishing the wage and job opportunities of black Americans.

As a lawmaker, Sessions went on to develop a reputation for his firm commitment to the rule of law, so much so that a vote against Sessions for Attorney General could stand to imperil conservative Democrats— such as Sens. Joe Manchin, Claire McCaskill, and Joe Donnelly— as it could be viewed as a decision to throw in with Chuck Schumer against law and order.

Sessions “is the most popular person in Alabama except for maybe Nick Saban. And it’s all earned in my opinion,” Tucker Carlson said in 2014, noting that Sessions made history by running unopposed in both his last primary and general election contests.

“For twenty years, Sen. Sessions has been representing a state whose population is nearly one-third African American,” one Republican operative recently told Breitbart. “If he were as bad as the left is now falsely trying to paint him out to be, why didn’t they run a Democrat against him?”

As the late Senator Arlen Specter said upon looking back on the 1986 hearing, “My vote against candidate Sessions for the federal court was a mistake because I have since found that Sen. Sessions is egalitarian.”

As for Joe Biden, one of Sessions’ chief opponents in 1986, he told CNN in December, “The president should get the person that they want for that job, as long as they commit, under oath, that they are going to uphold the law.”

While he would not go so far as to admit his own error three decades ago, he acknowledged that he no longer regards Sessions as insensitive to race. “People change,” Biden said simply.

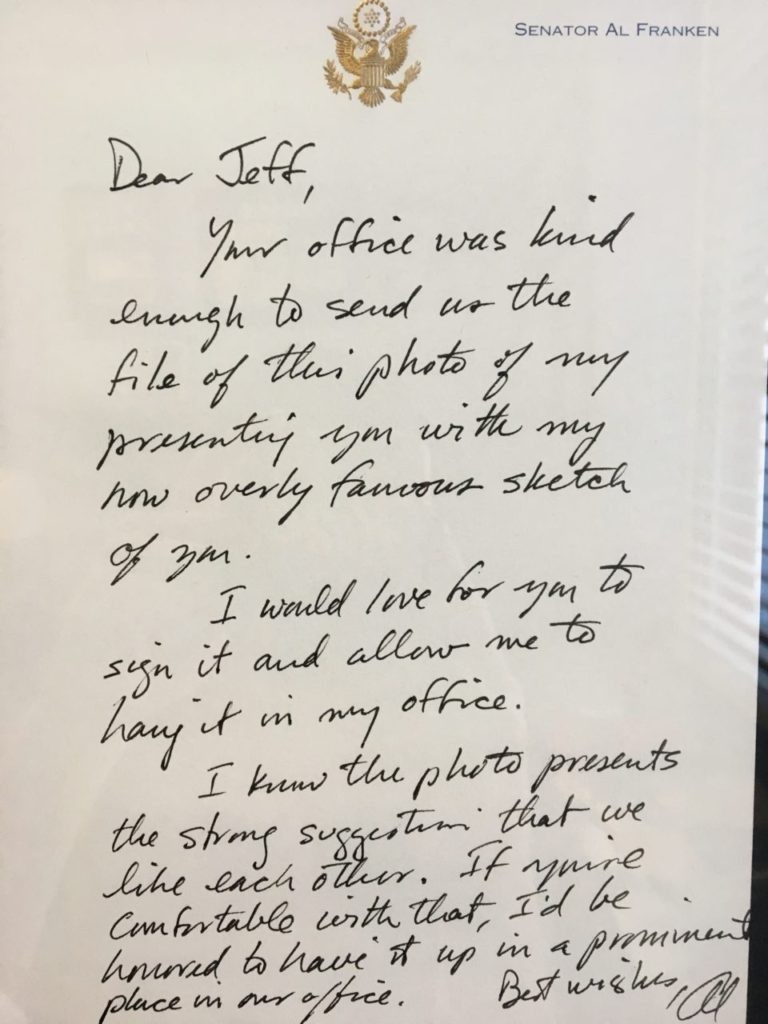

As Alabama’s elected representative, Sessions eventually came to sit upon the very Senate Judiciary Committee that rejected him— harboring no ill will nor animosity towards the men who opposed him, but instead becoming their partners and forging meaningful relationships with them, such as his friendship with far-left progressive Senator Al Franken.

With these men, Sessions spearheaded legislative reforms and never once voiced a complaint about their unfair treatment of him. Confident in his own dignity rendered to him by both his faith in God and the people of Alabama whom he represents, Sessions similarly never felt the need to plead his case publicly after all these years — assured in the belief that his own actions would speak louder than the allegations of his opponents.

While corporate media seems willing to allow a handful of partisans to resuscitate the discredited allegations of the ghosts of Democrats past to once again smear the good name of a decent public servant, those who know Sessions best say they are unwilling to “stand idly by” and let history repeat itself.

“Sen. Sessions is a good man and a great man. He has done more to protect the jobs and enhance the wages of black workers than anyone in either house of Congress over the last 10 years,” U.S. Civil Rights Commissioner Peter Kirsanow recently told Breitbart.

“I know him personally and all my encounters with him have been for the greater good of Alabama,” said Sen. Quinton Ross, the Democratic leader of the Alabama Senate who is also African American. “We’ve spoken about everything from civil rights to race relations and we agree that as Christian men our hearts and minds are focused on doing right by all people.”

“I should have volunteered to stand by his side and tell the story of his true character at his confirmation hearing,” Donald V. Watkins, an African American who attended law school with Sessions, wrote on his Facebook page. Watkins recalled how Sessions was the first white student to invite him to join a campus organization, LifeZette reports. “The fact that I did not rise on my own to defend Jeff’s good name and character haunted me for years,” Watkins wrote. “I promised Jeff that I would never stand idly by and allow another good and decent person to endure a similar character assassination if it was within my power to stop it.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.