Second of Three Parts

Theodore Roosevelt Spells Out the Two Republican Traditions: Cloth Coat and Fur Coat

by Virgil, with Theodore Roosevelt

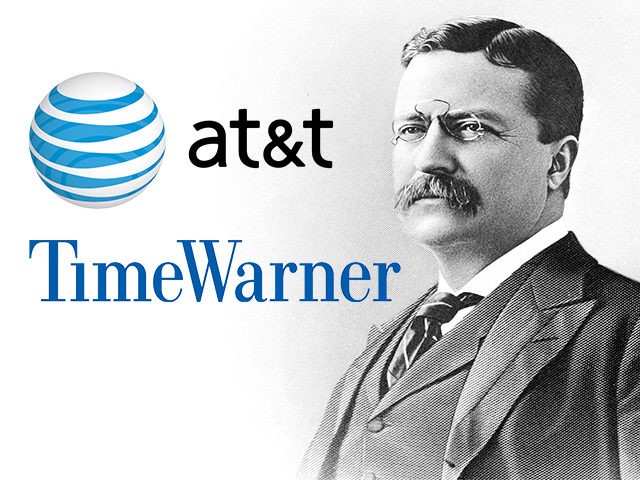

In Part One of this series, I described the curious partisan inversion that has occurred in the wake of the proposed AT&T-Time Warner deal: Donald Trump has come out against it, and Hillary Clinton appears to be, quietly in favor of it. In other words, the Republican presidential nominee, representing the supposed party of big business, is now on the “anti-corporate” side, while the Democratic presidential nominee, representing the supposed party of ordinary working people, is seemingly on the “pro-corporate” side.

To help me wrestle with the implications of this improbable flip, I, ghost that I am, have turned to another ghost. Namely, the shade of Theodore Roosevelt, America’s 26th president, serving from 1901 to 1909.

In his day, Roosevelt—like Trump, a rich New York City-born Protestant—was also an improbable figure. He was a war hero, a sub-cabinet appointee in two Republican administrations, and was also, in 1898, elected governor of New York State. Yet even so, he was out of step with many, perhaps most, of his fellow Republicans on key issues—in particular, business regulation. Notably, TR was a critic of the Republican stand-pat attitude toward business abuses. And, not to put too fine a point on it, he viewed orthodox Republicanism as retrograde and reactionary, hopelessly outmoded in an era of rapidly swelling national needs.

Roosevelt was elected to the vice presidency in 1900, and while that was certainly an honor for him, it was also seen, by New York’s Republican political bosses, as a clever way of getting him out of Albany—and out of their hair. Nobody foresaw that President William McKinley would be assassinated in September 1901, thus elevating TR to the presidency.

In office, one of President Roosevelt’s trademarks was his association with “trustbusting”—that is, antitrust enforcement, which was seen as a necessary response to the corporate behemoths that had grown to dominance in the mostly unregulated 19th century. Indeed, it was common to see political cartoons of TR as a muscular trustbuster, personally battling piratical tycoons.

And while Roosevelt passed from earth’s mortal coil in 1919, happily for me, he still pays close attention to the news.

So amidst the rolling mists of Eternity, as Breitbart’s most roving of roving correspondents, I was pleased to score an exclusive interview with The Colonel. (Yes, he liked to be called that, because, of all the many things he did in his life, he was most proud of his service with the First US Volunteer Cavalry Regiment—a unit he had formed—in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. His daring 1898 charge up San Juan Hill in broad daylight, against the entrenched Spanish infantry, ultimately earned him a Congressional Medal of Honor.)

So what follows is a transcript of my interview with Roosevelt:

Virgil: Mr. President, Colonel, thanks for taking time to speak with me.

Theodore Roosevelt: Oh, enough with the formal folderol, Virgil! Or else I’ll start calling you “Publius Vergilius Mero.” So please, just call me “Theodore.”

V: Okay. You prefer “Theodore,” not “Teddy”?

TR: Yes . . . I haven’t liked “Teddy” for a long time. [Virgil has since learned that Roosevelt’s first wife, Alice, had called him “Teddy”; after she died in 1884, he didn’t wish to hear that nickname any more.]

V: Got it. Well, uh, in any case, the subject at hand is big corporations and their combinations. So I’ll get right to it: What do you think of AT&T’s pending purchase of Time Warner? I mean, as a famous trustbuster, you always had an unorthodox view of antitrust for a Republican. So now, do you agree with Donald Trump?

TR: Actually, skepticism about big corporations and their doings is not quite so unorthodox for Republicans as you might think. I was always, I would say, part of a strong tradition within the Party. Since its inception in 1854, there has always been that tradition of skepticism about big business among many Republicans.

V: Gee, I hadn’t known that.

TR: Yes. The Grand Old Party, when it was, in fact, the Grand New Party, got its start on Main Street, in Ripon, Wisconsin, to be precise, back in 1854. To be sure, others claim that honor for another small town, Jackson, Michigan.

Yet either way, Ripon or Jackson, the Republican Party most definitely got its start among the farmers, free laborers, and merchants of the Midwest, not on Wall Street. To put it another way, the GOP was the little-guy party, at a time when the Democratic Party—which had its own populist tradition, going back to Andrew Jackson—had been taken over by the Southern plantation slaveowners.

V: Hmm. I had always thought of the Republicans as the party of robber-baron railroad tycoons.

TR: Yes. that’s a common misconception. Oh sure, the railroads were a big factor. Particularly in the North, which had industrialized sooner than the South, the railroads were akin to what Silicon Valley is today—the vital infrastructure of the age, as well as an economic locomotive, if you’ll pardon the wordplay.

And yet precisely because the railroads were so huge, they had a massive influence on both parties. When Commodore Vanderbilt, owner of a half-dozen big railroads, wanted to take control of the New York State legislature and use it for his personal gain, he just showed up in Albany with a trunk full of cash, doling it out to whomever would do his bidding, regardless of partisan label. And that was true across the country.

Yet even so, as often as not, the early Republicans were true to their roots among the workingmen, even if that conflicted with the interests of the railroadmen. For example, here are the words of the first Republican president, Abraham Lincoln, in his message to Congress, December 3, 1861. As you can see, Honest Abe was explicit about the greater importance of labor over capital:

Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration.

V: Interesting.

TR: Now it’s worth pointing out that Lincoln actually had been a lawyer for the railroads back in Illinois in the 1850s. Moreover, by his own bootstrapping nature, he was a strong believer in private property and free enterprise. However, he saw something crucial: There had to be a balance between capital and labor, and the government—hopefully, a Republican government—had to calibrate that balance, always making sure that the interests of workers and small landholders were protected.

Lincoln’s idea of balance held true for labor relations, such as they were, and it held true, also, for the general management of the economy, including imports and foreign trade. Interestingly, the most influential American economist of the 19th century was a man who was a believer in capitalism and property, but at the same time, a staunch opponent of unregulated laissez-faire.

V: Who was that?

TR: Henry C. Carey. He’s a man forgotten today, but his 1851 magnum opus, The Harmony of Interests: Agricultural, Manufacturing, and Commercial communicates its essence in its title: A happy country needs rules and guidelines that keep all sectors in harmony. In other words, rules. Carey was a conservative, ideologically, but at the same time, he could see the necessity of governmental action to preserve equilibrium.

You see, unlike today, when many Republicans regard the free market as the solution for everything, back then, Republicans thought more about social harmonies. That is, they were conservatives. After all, the hallmark of conservatism has been its reverence for such non-market-based concepts and institutions as culture, tradition, and church. By contrast, those who bow down to the market, only, inevitably see everything as being for sale—the only issue is the price. And that’s a very different concept.

V: Interesting. And yet today’s “conservatives” mostly pride themselves on their devotion to the free market.

TR: Those who are devoted to the free market—above God, country, and family—are really libertarians, not conservatives. That is, they are the followers of a liberal tradition; they want to liberalize and liberate things—everything.

V: Really? I hadn’t thought of it that way.

TR: Yes, there’s a recent phrase, coined by an avowed libertarian at the Cato Institute, seeking to instantiate this ultimate unity: He has called this synthesis “liberaltarian.”

V: Fascinating.

TR: So back to Lincoln. He was an emancipator, for sure, but was always mostly a conservative. As an aside, I’ll note that in his first inaugural address, Lincoln offered an extended hymn to our sacred union. It was a strictly conservative peroration, a celebration of non-monetary values; it had nothing at all to do with market forces. Have a listen:

The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

V: I see, good point.

TR: Okay, so now, more on Lincoln’s conservative economics, which were, always, focused on balance and harmony. Even as he praised labor and described it as “prior” to capital, he was also eager to make room for capital, too. In that same 1861 speech to Congress, he said:

Capital has its rights, which are as worthy of protection as any other rights. Nor is it denied that there is, and probably always will be, a relation between labor and capital producing mutual benefits.

Again, that’s the point: mutual benefits—harmony. His goal, and the goal of all conservatives, is actually to have no class warfare and no civil war.

V: Although, of course, tragically, America got both.

TR: Yes, those were tumultuous times. But Lincoln and the Republicans, I am proud to say, managed to steer the ship of state through those stormy seas to safe harbor.

V: Okay, that’s an interesting history lesson. So what about antitrust?

TR: My dear man, you asked me a question, and I am answering it. Give me time!

V: Yes, sir.

TR: As the 19th century moved along, it became apparent that more had to be done to curb the power of what was becoming Big Business. That is, not just the railroads, but all the corporate “trusts,” as we called them back then.

And once again, in formulating the national response, it was Republicans who took the lead. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was authored by Sen. John Sherman of Ohio, a Republican.

V: The brother of William Tecumseh Sherman, the Union general in the Civil War?

TR: Yes, quite so. They were both good men. And the Sherman Act, I might add, was signed into law by a Republican president, Benjamin Harrison.

V: So you’re saying that antitrust is a Republican cause?

TR: At times, it has been, and then, at times, not. To borrow the phrase from the poet Walt Whitman, the Republican Party, like the Democratic Party, “contains multitudes.”

And so now, in this historical quickmarch, let’s now skip ahead a few years, to 1896. In that year, we saw the election of a great man, William McKinley.

V: Hmm. If you say so. Isn’t McKinley, the 25th president, remembered as a tool of big business, a puppet in the hands of his puppet-master, the industrial magnate Mark Hanna?

TR: Yes, unfortunately, that is the way President McKinley is remembered, and it’s neither a fair nor accurate memory. He was in reality a talented fellow, who, when young, was forced by financial exigency to drop out of college; he then worked as a postal clerk and schoolteacher before enlisting as a private in the Union Army in 1861. And after four years of bloody combat, he had risen to the rank of major.

Later he was elected to Congress from Ohio, and then, in ’96, to the presidency. And, once in the White House, President McKinley was then kind enough to select me as his running mate in 1900 when he sought re-election.

V: And after the McKinley-Roosevelt ticket was victorious, he was assassinated.

TR: Yes, he died on September 14, 1901; it was a terrible tragedy. As I said to Congress after his death, “He was the most widely loved man in all the United States”—except of course, by one evil anarchist, Leon Czolgosz, whom we nowadays would call a “terrorist.” Moreover, in paying tribute to my boss and my friend, I reminded my audience that he was no economic royalist but, rather, a true cloth-coat Republican:

President McKinley was a man of moderate means, a man whose stock sprang from the sturdy tillers of the soil, who had himself belonged among the wage-workers.

V: Okay, you’ve convinced me: There were plenty of lunchpail Republicans back then. So how did this image of the Republicans as the party of plutocracy get started? Has it all been media bias?

TR: As I said, Main Street Republicanism was one strand of the Party. Another strand was Big Business and Wall Street Republicanism.

And within the GOP, the big shots, too, had their champions, such as the dreadful Sen. Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island, whose daughter married John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Aldrich was a reactionary, or, as I liked to call him and his ilk, a “malefactor of great wealth.”

V: So there were two Republican parties, or sub-parties, or factions.

TR: Yes. I was astride one, and Aldrich was astride the other. And we fought like the dickens. When I was a young man, back in the 1880s, the reactionary faction was known as the “Stalwarts,” and as for the progressive faction, we were called “Half-Breeds.”

V: I guess “Half-Breed” is too politically incorrect for this era.

TR: Yes, I suppose so. But by any terminological dichotomy—Main Street vs. Wall Street, mossback vs. reformer, conservative vs. progressive—the split has been real and ongoing, stretching out as it has a century-and-a-half. Both sides have had their victories and their defeats.

From my vantage point in the Oval Office—that was a structure, by the way, that I added to the White House, as part of the West Wing, in 1902—I could see that the rising tide of discontent had to be dealt with in a constructive manner.

You see, William Jennings Bryan, a fire-breathing populist whom I loathed, had taken over the Democratic Party in 1896. Bryan had some good ideas, such as the advancement of workers’ rights, but he was also irresponsible—I thought of him as a danger to the republic.

Happily, McKinley beat Bryan in the ’96 presidential election, and again in ’00, and yet even so, it was obvious that Bryan had a substantial constituency; the populist upswell was going to continue, because economic conditions were harsh and times were indeed hard.

So something had to be done to improve the lot of workers and farmers, all the while maintaining the basic order of things. And I felt that I was the man to do it. I called my policy program the Square Deal.

V: Sounds a bit like the New Deal of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

TR: Well, Franklin was my cousin and, I daresay, a fan of mine.

V: In any case, whatever the name, your goal was to stave off all that populist energy.

TR: Yes, exactly. But I knew that I couldn’t stop domestic radicalism with reaction—that just feeds it. Instead, I had to stop radicalism with prudent preemption. As I think Edmund Burke said, the task of the statesman is to channel the tides of change through the canals of custom.

V: Ooh, I like that.

TR: Yes, I love Burke.

V: So now to antitrust?

TR: I’m getting there!

In that same message to Congress in 1901, delivered just three months after I was sworn into office, I took the antitrust issue head on. I began by reiterating the basic conservative Republican wisdom of the harmony of interests, because, ultimately, all Americans are in the same boat. As I said:

The fundamental rule in our national life–the rule which underlies all others–is that, on the whole, and in the long run, we shall go up or down together.

I might note that that’s the sort of “One Nation” rhetoric used a few decades before by the great British conservative leader and prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli. That was his big idea: He could not let his country sunder, split apart, over class divisions and class warfare. And that’s exactly what I thought, too.

And yet at the same time, in our search for solutions, we couldn’t go blundering around, armed only by sentiments, as opposed to sapience.

V: I love latinate words!

TR: As I also said:

The mechanism of modern business is so delicate that extreme care must be taken not to interfere with it in a spirit of rashness or ignorance.

V: Okay, got it. But again, where does antitrust fit in?

TR: Virgil, you seem to be in rather a hurry. When, in fact, we both are in a place where the passage of time is measured in eons.

V: Yes, Colonel—I mean, Theodore—but back on earth, there’s still such a thing as time-scarcity. They’re called deadlines.

###

Hi, this is Virgil: Speaking of deadlines, and other matters of time-scarcity and time-urgency, this is probably a good place to take a break.

We will conclude my exclusive interview with Theodore Roosevelt in the next installment.

Coming in Part Three: TR explains his theory of antitrust, and adds his explanation as to why size doesn’t always matter.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.