The Gunma Prefecture of Japan last week removed a memorial to Korean victims of Imperial Japan’s forced labor policy during World War II.

Lawmaker Sugita Mio of Japan’s governing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) said the demolition was a “relief” and hoped other “memorials and statues of ‘comfort women’ or Korean workers” would soon be removed.

The Gunma memorial was constructed by a Japanese civic group in 2004 to promote “public understanding” of the 1910-1945 Korean occupation and to celebrate the (hopefully) growing friendship between modern Japan and South Korea.

The memorial, located in a public park, consisted of a cenotaph and a four-meter-tall golden monument. The cenotaph bore three plates inscribed with the words “Remembrance, Reflection, and Friendship” in Korean, Japanese, and English.

The memorial included some text describing the forced labor situation in wartime Korea, with wording that was hotly debated at the time of its construction because some of the suggested phrasing was felt to be either too harsh on Japan or not harsh enough. The goal was to create a monument that would inspire respect and reflection without unduly alienating Japanese visitors.

Critics of the memorial nevertheless denounced it as “anti-Japanese” and the civic group that built it began holding commemoration ceremonies at other locations to avoid focusing too much negative attention on the park.

In 2014, the government of Gunma said some of the comments made at these memorials were unacceptable attempts to influence contemporary Japanese politics and chose not to renew the ten-year permit again, setting the memorial up for demolition in 2024. Verbiage that states Japanese forces kidnapped or enslaved Koreans seems to be controversial.

Visitors in old Japanese Imperial army uniforms enter Yasukuni Shrine, which honors Japan’s war dead, Aug. 15, 2022, in Tokyo. (AP Photo/Eugene Hoshiko)

Advocates of the memorial sued to preserve it, but the Tokyo High Court ruled against them, saying the monument could no longer be considered politically neutral. The Supreme Court rejected an appeal in 2022 and, when the citizens’ group refused to dismantle the monument as ordered last April, the prefecture made plans to remove it.

“The very existence of the memorial has become a subject of political controversy,” lamented Gunma Gov. Yamamoto Ichita at a January 25 news conference.

Yamamoto said his administration “carefully negotiated and coordinated” with the creators of the memorial to find an alternate location, but since “we could not get their approval,” the memorial was destroyed.

“We are a nation governed by the rule of law, so we have no choice but to carry out this solemnly,” the governor declared.

“It is not a matter of historical awareness, but rather the fact that a rule that had been set in the first place was broken. The removal is not connected to the twisting of history,” he insisted.

“Even the local government knows what it’s doing is shameful. Why else would they be removing it under wraps?” retorted 74-year-old Fujii Yasuhito, one of the activists who created the memorial. The park was cordoned off with a heavy police presence while the monument was destroyed.

“Removing the memorial is an attempt to erase Japan’s history of wrongdoing. Even if the memorial is removed, the spirit of remembrance, reflection and friendship with Koreans will live on,” he vowed.

The prefecture moved quickly once it was time to act, obliterating the monument in three days flat, smashing the base of the stone into rubble, and handing the “Remembrance, Reflection, and Friendship” plates over to the memorial’s advocates in a melancholy finale.

Forced labor and “comfort women” — Korean women forced into prostitution by occupying Japanese forces — remain a very sore subject in both Japan and Korea to this day. That would include both Koreas, as the North Korean regime denounced the Gunma demolition as a “violent act of fascism” on Tuesday.

“This is an intolerable and inhumane act that once again hurts the wounds of victims of forced labor and their descendants,” said the state-run Korea Central News Agency (KCNA).

“Gunma Prefecture authorities should understand the consequences of the current situation that has sparked an unbearable anger and immediately restore the memorial stone,” KCNA demanded.

Kim So-youn, Tokyo correspondent for South Korea’s Hankyoreh, lamented the “ruthlessness with which the memorial was demolished” — a heavy hand that suggested Gunma officials either do not know its full history or do not want that history to be remembered.

Kim pointed out the monument was built in Gunma because some 500 enslaved Korean workers died there. The base of the memorial was painted with a compass to show their restless spirits on the way home to Korea.

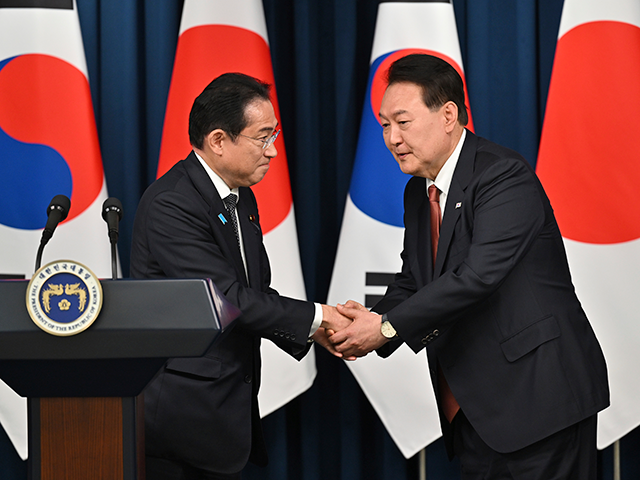

South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol, right, shakes hands with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida during a joint press conference after their meeting at the presidential office in Seoul Sunday, May 7, 2023. (Jung Yeon-je/Pool Photo via AP)

“The memorial’s removal clearly demonstrates that improved relations between Prime Minister Kishida Fumio and President Yoon Suk-yeol – who has spent his term brushing under the rug issues related to Korea’s unfinished history with Japan, such as the compensation for Korean victims of forced labor – are not based on ‘friendly relations,’ but rather the erasure of history,” Kim charged.

Current South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol has made some efforts to put the forced labor controversy to bed, including a plan announced in March 2023 to settle all outstanding issues of compensation for forced laborers and comfort women. Relations between Japan and South Korea became very tense under Yoon’s predecessor Moon Jae-in, as South Korean courts issued rulings against Japanese companies for wartime labor abuses, and Tokyo warned Seoul not to enforce them.

Nationalist Japanese lawmaker Sugita Mio enthusiastically applauded the demolition of the Gunma memorial and suggested taking down a similar monument located at a long-shuttered mine in Kyoto next.

“This is a statue of a conscripted worker in Kyoto, which was erected before even those in Korea. Since it is on privately owned land, it won’t be easy to get removed. I hope we will be able to see it brought down soon,” Sugita said of the next statue she wants to take down.

The Kyoto statue was built by South Korea’s two big trade unions in 2016 and was soon followed by four identical monuments in Seoul and other South Korean cities, so pulling it down would probably raise tensions between Japan and South Korea considerably.

The group that agitated for destroying the Gunma memorial, Soyokaze (“breeze” in Japanese) wants to eliminate all of Japan’s WW2 memorials to forced labor in Korea.

Many other Japanese posted on social media that they were horrified by the Soyokaze campaign and Sugita’s comments because they did not wish to anger Koreans or whitewash Imperial Japan’s atrocities. Hundreds of people protested the removal of the Gunma memorial and thousands of Japanese artists signed a petition attempting to protect it.

People hold candles and signs during a rally against the South Korean government’s announcement over the issue of compensation for forced labor in downtown Seoul, South Korea, March 6, 2023. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

Gunma University associate professor of constitutional law Fujii Masaki told Asahi Shimbun that contrary to Gov. Yamamoto’s statements, the prefecture was not obliged to remove the moment after Japanese high courts shot down lawsuits to reinstate the permits. The prefecture could simply have left the monument alone.

“Given that commemorations have not been held in front of the memorial for more than ten years, the prefectural government should ‘reconsider the matter in light of public opinion,’ among other responses, but its single-minded focus on removing the memorial has only fueled confrontation,” he remarked.

Fujii said the memorial came down because the government felt it was too “troublesome” to keep around. He warned that its destruction would “please those who take a hostile view of its very existence and, as a result, it could encourage historical revisionism.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.