Freedom House marked the 50th anniversary of its “Freedom in the World” report with the 2023 edition, which offered the grim observation that “global freedom declined for the 17th consecutive year,” and warned, “the struggle for democracy may be approaching a turning point.”

The struggle seems to have passed a turning point in Hong Kong, which the Cato Institute said has descended into outright “tyranny” in its own Freedom Index.

Advocates for nearly any cause have something of an institutional bias for claiming that every year was worse than the one before, in part because a sense of perpetual crisis is vital to their institutional importance and fundraising and in part because analysts are predisposed to find evidence of whatever problem they are looking for.

“Freedom” can be an especially tricky blessing to define and seek out. Freedom advocates have different measures of how much liberty exists in a society, and which freedoms are the most valuable — an important metric because sometimes one freedom can only be enhanced by restricting another. The difference between nominal authoritarianism and the daily freedoms enjoyed by most citizens can be considerable. Some societies just look better on paper than they do in practice.

For example, Freedom House tends to equate abortion rights with freedom, but the abortion laws under Roe vs. Wade were nakedly authoritarian — the issue was decided at the national level by a group of Supreme Court justices and no further democratic debate was welcome.

Abortion rights demonstrators rally to mark the first anniversary of the US Supreme Court ruling in the Dobbs v Women’s Health Organization case in Washington, DC on June 24, 2023. (ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS/AFP via Getty Images)

Under the recent Dobbs decision, the “constitutional right to abortion” was supposedly “taken away,” but now people in the 50 states get to vote on the issue and, in many cases, they have voted for more liberalized abortion laws.

Which was the higher state of “freedom” and “democracy?” Should freedom be judged by the process or by the outcome? The number of abortions has reportedly declined across the country since the Dobbs decision. Will that outcome seem more or less “free” to the children who would not have been born under Roe v. Wade?

These are weighty questions. Freedom arguably grows more difficult to define as the size of government swells, the volume of laws explodes, and modern communications make it possible for people to interact in so many new ways. Interaction naturally invites the threat of compulsion, which is the death of freedom. People manipulated by social media algorithms or kicked off platforms are losing freedoms that previous generations did not know they had.

Freedom House can back up the claim that worldwide freedom has been slipping under its own metrics for the past 17 years. Its 2006 report was relatively upbeat, buoyed by a “positive trend” toward democracy in the Middle East, a smidgen of democracy in the former Soviet Union, and a modest contraction in the number of countries rated “not free.” One of the big increases in freedom was registered in Ukraine, which is today fighting to avoid being crushed beneath the boot of an authoritarian warlord.

“The overall picture was distinctly positive,” Freedom House said at the end of 2006, for the last time to date. In 2023, it listed “Moscow’s war of aggression,” coups in places like Burkina Faso and Niger, increasingly oppressive juntas like the one in Myanmar, and crackdowns by authoritarian governments like Turkey as reasons for pessimism.

The best thing documented about 2023 was the end of most pandemic restrictions, which could not help but increase “freedom of assembly and freedom of movement.” Also, democratic alliances “demonstrated solidarity and vigor,” while authoritarians like the ones in Beijing and Tehran wound up with egg on their faces. The big question, of course, would be whether the pratfalls of inept tyrants actually loosen their grip on power.

The Cato Institute’s gloomy report on Hong Kong offers an example of a government so clumsy and foolish that it sparked a world-historic pro-democracy uprising four years ago — and then crushed it completely with an iron-fisted “national security law,” rules that only loyal Communist robots can run for office, show trials for dissidents, and other horrors.

Members of the League of Social Democrats (LSD) hold a banner outside the West Kowloon Magistrates’ Courts during a hearing for 47 pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong, China, on Monday, Feb. 6, 2023. (Lam Yik/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

“Hong Kong’s descent into tyranny is a tragedy,” Cato said, sadly recalling that the island used to be “one of the freest places in the world.” Cato’s report said the loss of freedom in Hong Kong would have been even more shocking if the Wuhan coronavirus pandemic had not pushed worldwide freedom levels down at the same time China was strapping Hong Kong into a torture chair.

“Given ongoing attacks on freedom in Hong Kong, we will be surprised if future reports do not show a continuing and pronounced degradation in the territory’s ratings, including a noticeable decline in economic freedom,” Cato warned.

The Cato Institute has a libertarian outlook, so its freedom metrics are a little different from Freedom House. For instance, Cato considers “size of government” to be a reliable indicator, which is usually a safe bet, although some areas like Africa have problems with weak and indolent governments that do not act aggressively enough to keep their citizens free from each other. Cato is much more interested in “sound money” and economic liberty as indicators of overall freedom.

Freedom House puts a great deal of stock in “democratization,” which again is usually a safe bet, as people who can vote in fair elections tend to be more jealous of their freedom. Unfortunately, people can also vote themselves into some very dark corners, and “democracy” is too often used as a cover for unlimited government growth. Citizens are sadly prone to thinking they cannot be living in a tyranny if they can “vote the bums out,” but sadly this is not true.

The level of physical force deployed against citizens is also a less reliable metric of true freedom than it used to be. The Internet has introduced new opportunities to manipulate and compel people without ever pointing a gun at them. The entire battle over “disinformation” is really an argument about coercion achieved through manipulating information, rather than using brute force. The punch line is that “fighting disinformation” has become a go-to excuse for making societies less free.

Freedom House spotlighted a fascinating case study in the contradictions of freedom by blasting President Nayib Bukele of El Salvador for using his “parliamentary supermajority” to “undermine democratic controls,” particularly with his aggressive war on gangs:

In March 2022, the legislature approved his request for a state of exception intended to address gang violence, which has led to the indefinite detention of tens of thousands of people, with little regard for their due process rights. Under the state of exception, authorities have also suspended anticorruption mechanisms that would shed light on government spending and contracts. In September, Bukele announced that he would compete for a second term, a year after the Constitutional Court – newly packed with his appointees after a wholesale purge – overturned a ban on consecutive presidential terms.

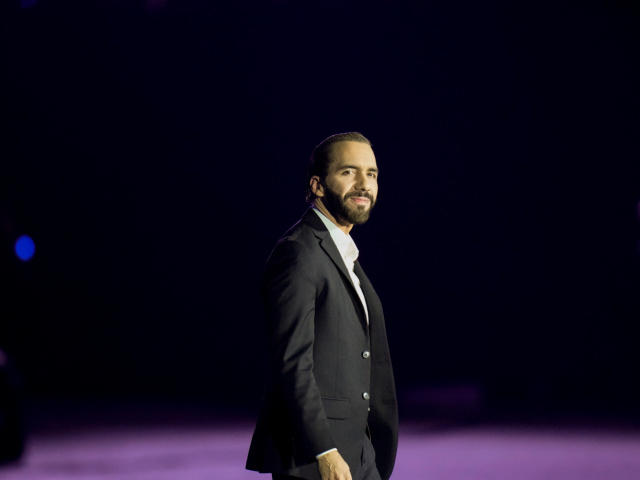

All true — and yet Salvadorans overwhelmingly consider themselves to be freer under Bukele, who will probably romp to reelection. He is the most popular elected leader in Latin America, and arguably in all of the Americas, all the way up to Ottawa.

Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele walks on the stage after speaking during the opening ceremony of the Central American and Caribbean Games in San Salvador, El Salvador, Friday, June 23, 2023. (AP Photo/Arnulfo Franco)

In this photo provided by El Salvador’s presidential press office, inmates identified by authorities as gang members are seated on the prison floor of the Terrorism Confinement Center in Tecoluca, El Salvador, March 15, 2023. (El Salvador presidential press office via AP)

Bukele’s supporters feel he has greatly enhanced their freedom by restoring order. He claims to have virtually eliminated homicide in what used to be the murder capital of the world. Fumbling to understand his enduring popularity, the Miami Herald wailed in July that “Latin Americans are so fed up with violence that many of them are willing to support a wannabe autocrat who is perceived to be tough on crime.”

Is that willingness irrational? Bukele’s notion of “due process” is different than the American standard. He brags about building the “biggest prison” on the continent and marching 40,000 half-naked accused gang members into it. He has referred to himself as “the world’s coolest dictator.”

Is El Salvador more, or less, free because of him? Were some freedoms compromised so that others could flourish — and was that a wise trade-off? What happens after Bukele is gone? Is China right to argue that Hong Kong gained much-needed stability and public order by giving up some freedoms it didn’t really need? On such questions does the fate of freedom around the world depend because we cannot know if we are losing freedom unless we can measure it.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.