The World Health Organization (W.H.O.) announced on Monday it would renew the status of the coronavirus pandemic as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), acknowledging the pandemic is at a “transition point” but noting a “substantial decrease” in government data on the spread of the virus.

The W.H.O. made multiple optimistic statements on the status of the pandemic and as recently as last November celebrated the documentation of a 90-percent drop in coronavirus-related deaths worldwide between February 2022 and November. The global agency’s tone surrounding the pandemic changed dramatically in December, however, following the decision by the Chinese Communist Party to “optimize” that nation’s repressive lockdown and quarantine policies in the face of large-scale nationwide protests.

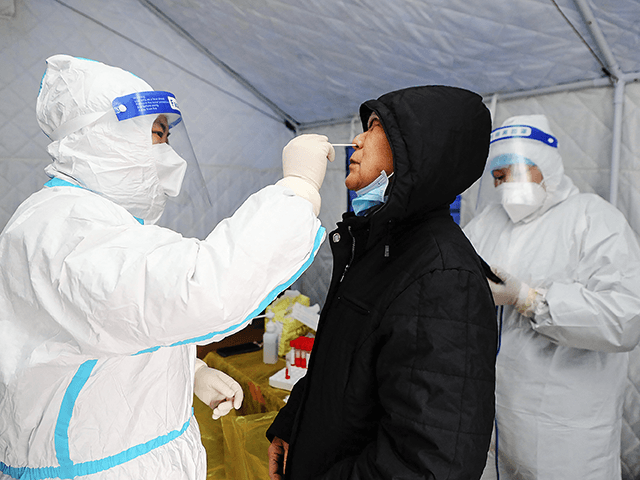

Beijing dropped regular testing, allowed those with mild coronavirus cases to treat them at home rather than imprisoning them in a dingy quarantine camp, and insisted on counting only those dying of respiratory failure as coronavirus deaths. The new measures, W.H.O. officials objected, resulted in China obscuring critical data necessary for that agency to properly assess the status of the epidemic within China and its potential impact on the rest of the world.

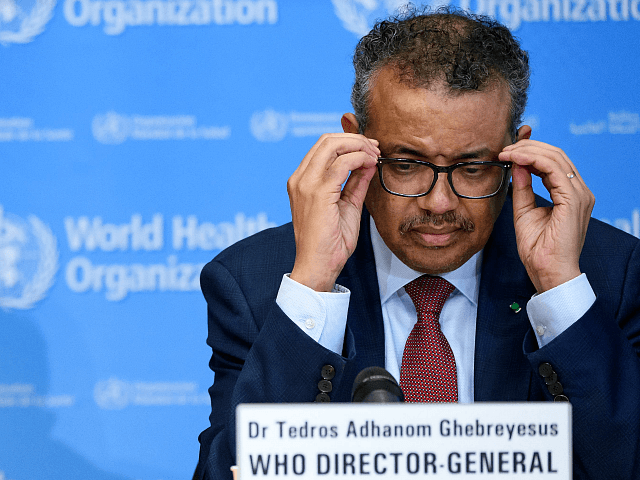

W.H.O. Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus attended a meeting on Friday with the agency’s emergency committee to discuss renewing the PHEIC designation. Tedros issued the declaration three years ago last week, ceding to Chinese government pressure not to do so for weeks despite evidence the W.H.O. was aware of the highly virulent infectious disease spreading out of Wuhan, China, as early as December 2019.

According to a summary of the meeting published by the W.H.O., Tedros admitted that the pandemic was “probably at a transition point,” meaning ebbing from the peaks seen in previous years, but asserted that governments’ resources to address the pandemic were simply “hobbled in too many countries” for the W.H.O. to responsibly end the emergency.

“While the world is in a better position than it was during the peak of the Omicron transmission one year ago, more than 170,000 [coronavirus]-related deaths have been reported globally within the last eight weeks,” the agency paraphrased Tedros as saying. “In addition, surveillance and genetic sequencing have declined globally, making it more difficult to track known variants and detect new ones.”

The W.H.O. summary returned to the issue of insufficient tracking and data repeatedly.

“The WHO Secretariat expressed concern about the continued virus evolution in the context of unchecked circulation of SARS-CoV-2 [the virus that causes coronavirus infections],” the agency noted, “and the substantial decrease in Member States’ reporting of data related to [coronavirus] morbidity, mortality, hospitalization and sequencing, and reiterated the importance of timely data sharing to guide the ongoing pandemic response.”

Tedros issued multiple recommendations to state actors, among them to “improve reporting” of data to the W.H.O.

The summary of the meeting did not identify any country by name as having an outsized impact in the declaration, yet the W.H.O. spent much of December and January specifically urging the Chinese Communist Party to track coronavirus cases and death appropriately.

Health workers in protective gear walk out from a blocked off area after spraying disinfectant in Shanghai’s Huangpu district. (Photo by STR/AFP via Getty Images)

Tedros’ own tone in W.H.O. press briefings towards the status of the pandemic indicated a significant improvement in the status of the public health fight for much of the second half of 2022.

“Last week, the number of weekly reported deaths from [coronavirus] was the lowest since March 2020. We have never been in a better position to end the pandemic,” Tedros announced at a press conference in September. “We are not there yet but the end is in sight.”

Tedros peaked in positivity in mid-November.

“Just over 9,400 [coronavirus] deaths were reported to W.H.O. last week, almost 90 percent less than in February of this year, when weekly deaths topped 75,000,” Tedros announced at the time. “We have come a long way, and this is definitely cause for optimism, but we continue to call on all governments, communities and individuals to remain vigilant.”

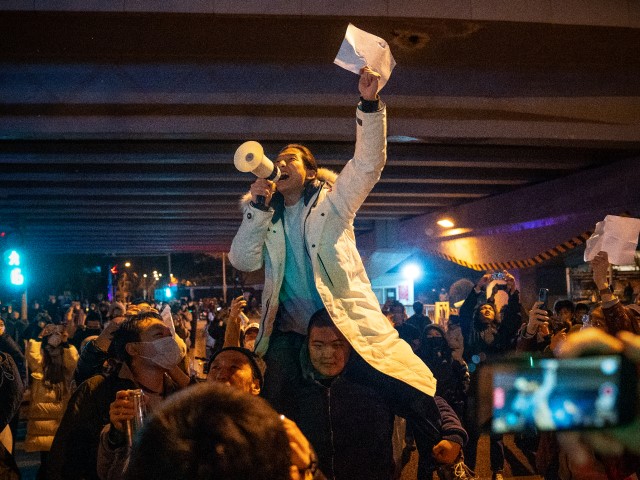

The return of intense concern over an eruption of cases followed that month. The Chinese government announced its “optimization” – essentially a plan to end most lockdowns and limit quarantine camp usage while not planning to expand access to cold medications, hospital care, or other key public health services – in December after hundreds of people took to the streets against communism in the last weekend of November. Outrage over a fire in Urumqi, East Turkistan – where dozens in a residential complex died as firemen, blocked by lockdown barricades, watched helplessly – prompted initial displays of dissent that erupted into riots and a movement known as the “blank paper” protests, in which participants hold up a blank piece of paper representing what the government allows them to say without arresting them.

What followed “optimization” were widespread reports of mass death, hospitals and morgues overflowing with patients, dramatic shortages of basic cold medications heavily regulated under the previous lockdown policy, and the disappearance of young people, particularly women, identified as having participated in the protests. Chinese authorities claimed to have identified minimal numbers of cases and deaths tied to the pandemic, but also admitted to severely reducing testing and restricting the protocol used to identify a coronavirus death.

A demonstrator holds a blank sign and chants slogans during a protest in Beijing, China, on Monday, Nov. 28, 2022. (Bloomberg via Getty)

Tedros and the W.H.O., asked to assess the situation in China, said in late December that China had not offered the necessary information for them to do so.

“In order to make a comprehensive risk assessment of the situation on the ground, W.H.O. needs more detailed information on disease severity, hospital admissions, and requirements for ICU support,” Tedros said at the time, adding he was “very concerned over the evolving situation in that country.”

“We continue to call on China to share their data and conduct the studies we have requested and which we continue to request,” Tedros urged. “As I have said many times before, all hypotheses about the origins of this pandemic remain on the table.”

In response to the anecdotal reports of widespread coronavirus illness, multiple countries imposed restrictions on Chinese travelers last month. Rather than condemn those restrictions, as the W.H.O. often does, Tedros said they were “understandable” because China had been so opaque in sharing information.

By January, Tedros and W.H.O. emergencies director Mike Ryan were accusing China of using improper protocol for identifying coronavirus deaths.

“W.H.O. still believes that deaths are heavily under-reported from China and this is in relation to the definitions that are used but also the need for doctors and those reporting in the public health system to be encouraged to report these cases and not discouraged,” Ryan said at a regular press conference on January 11.

Tedros told reporters that he could not necessarily trust global W.H.O. case statistics, blaming China’s poor reporting for what he called “certainly an underestimate” in deaths.

FABRICE COFFRINI/AFP via Getty Images

Chinese government statistics showed meager growths in the case and death rates for much of January. Independent attempts to tally these numbers found large increases in both. A Washington Post report from January 9 using satellite images around funeral homes and other similar data estimated that 5,000 people a day were dying of coronavirus in China. The Chinese Center for Disease Control (CDC) at the time had tallied a little over 5,200 deaths in the country since the pandemic began.

The “COVID-19 Data Repository” by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University – which does not use the Chinese CDC – stated at the time that China had documented a little over 1,500 coronavirus deaths in the past 28 days and 17,837 deaths since the pandemic began in central Wuhan.

Other coronavirus death estimates from abroad were even direr. Airfinity, a British data research firm, estimated in late January that Lunar New Year travel at the end of the month could result in 36,000 deaths a day nationwide.

The Lunar New Year, or Spring Festival, ended this weekend. The event was, prior to the pandemic, the largest travel event in the world. Chinese propaganda outlets depicted this year’s new year travel as bustling, normal, and healthy, making particular note of the hundreds of thousands of people flooding Wuhan, the origin location of the pandemic.

As of Sunday, the Chinese CDC not only did not report an increase in cases as millions traveled domestically and around the world, but claimed a dramatic drop in the spread of the virus.

“The Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said it recorded 6,364 deaths from January 20 to 26, down from 12,658 between January 13 and 19,” the South China Morning Post reported. “Covid-related respiratory failure caused 289 deaths in the seven-day period from January 20, while 6,075 deaths were recorded among [coronavirus] patients who had underlying diseases.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.