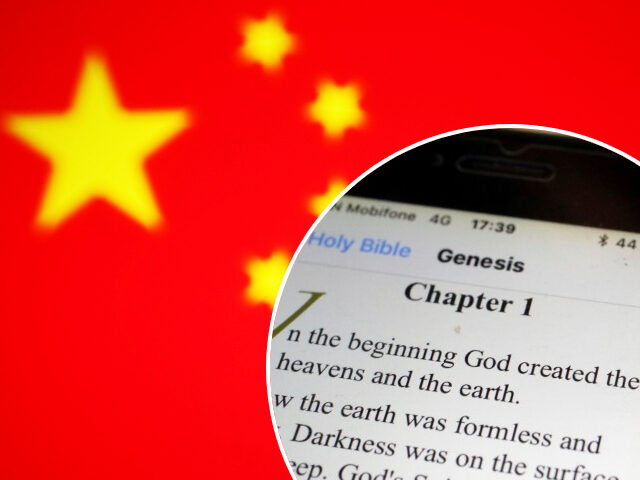

Experts testified before Congress on Tuesday that the Communist Party of China has extensively expanded its digital capabilities to censor — and effectively erase — religion on the internet, the latest step in a process of enforcing communism through the eradication of faith that the regime refers to as “Sinicization.”

“Sinicization,” as Chinese officials describe it, is a process to force religions to conform to Chinese culture. The Chinese government does not consider Chinese culture separate from communist ideology, and so in practice “Sinicization” has largely meant forcing religious leaders to promote communist propaganda and replace their faith with worship of Xi Jinping. In some cases, Communist Party authorities have forced Christians and Buddhists to replace religious symbols in their homes with photos of Xi Jinping.

The panelists at the hearing, titled “Control of Religion in China Through Digital Authoritarianism,” noted the implementation this year of a law that effectively outlaws all religious content online. Even members of the five legal religions in the country – the Chinese Catholic Church, the “Three-Self Patriotic” (Protestant) Church, Chinese Islam, Chinese Daoism, and state-controlled Buddhism – require a specific government license to post any religious content online, including videos of services or addresses from the clergy.

State repression, they added, was more severe against groups considered an elevated threat to communism, such as Tibetan Buddhists or Muslims in occupied East Turkistan, where China is currently engaging in genocide against indigenous people. It also affects, they added, the faithful abroad, as Beijing has endeavored to cut ties between those within its borders and believers in the free world.

The hearing was hosted by the Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC), made up of lawmakers from both parties and both houses of Congress.

The occasion of the hearing was, in part, the passage of a series of new regulations in March known as the “Measures for the Administration of Internet Religious Information Services.”

“Xi Jinping’s new regulation on religion … represents a new low for Xi and his government,” U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) chair Nury Turkel told the Commission on Tuesday. “Its impact cannot be understated, as the regulation imposes new restrictions on religious activities, further constricting the narrow space in which religious groups can operate.”

Turkel revealed that, in preparation to impose the regulations, “Chinese authorities have recruited hundreds, if not thousands, of auditors to target and censor religious content on the Chinese internet.”

“Christian and Tibetan Buddhist groups have reported that their websites and WeChat virtual groups were shut down and are no longer accessible … The regulation also imposes tighter restrictions on state-sanctioned religious groups,” he explained. “These groups are required to submit detailed information to authorities to apply for a permit to operate online.”

Turkel called the regulation “tantamount to a total ban on religious activities, as many groups are no longer able to operate in person or online.”

Chris Meserole of the Brookings Institution told the panel that, in addition to the literal censorship of religious activity and shutdown of religious gatherings in person, the law itself imposes a chilling effect, discouraging faith groups from even attempting to pray or engage in other religious acts.

“By eroding faith that the private exercise of religion is possible, digital surveillance works to erode faith altogether,” Meserole contended.

Meserole accused Xi of building “the world’s most comprehensive architecture for digital repression” generally, not just for religious repression, and added that the apparatus is so extensive that it affects people of faith “well beyond its [China’s] borders.”

“[T[he Chinese have also sought to leverage WeChat to monitor ties between Christian communities abroad and those in mainland China—to the point where domestic Chinese clergy have asked their members not to use WeChat with Christians in the United States,” he explained. He also noted that Chinese surveillance technology companies, such as Huawei and ZTE, have worked with dictatorships around the world to install similar projects to silence the citizens of those countries. Among the best-known iterations of these exported Chinese surveillance operations are the “Fatherland Card” system in Venezuela, the Huawei-built surveillance system in Uganda, and “ECU-911,” a pervasive spying operation also believed to have been built by Huawei under the socialist regime of Rafael Correa in Ecuador.

Espionage on civilians is not limited to those known to adhere to a religion, though religious persecution in China is among the most critical in the world – and the most diverse, affecting Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, and those of smaller spiritual groups such as Falun Gong practitioners.

Emile Dirks, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Toronto who has dedicated much of his work to studying Chinese repression, explained to the Congressional-Executive Commission on China that those who practice religion are among a larger group of individuals the regime refers to as “target people,” who is monitors out of fear they may one day challenge it.

“Target people is a broad group and can include everyone from users of drugs, to former prison detainees and people in community corrections, to people with mental illnesses, to petitioners, to human rights advocates, to members of ethnic or religious minority communities,” he noted. “These people are among the most marginalized and vulnerable members of Chinese society. The total number of Chinese citizens police have registered as target people is unknown, though it likely runs in the millions.”

Police have the technological capability to monitor the every move of a “target person,” making religious gatherings near impossible. Dirks suggested, however, that the human resources of Chinese police have not kept up with the technology such that, often, “there are too many target people, or too many competing tasks,” for police to subdue every desginated person.

The experts urged the American government to invest more heavily in education for studies on China, including language study in Mandarin and the languages most commonly used by those oppressed by the regime. Turkel, representing the USCIRF, also suggested “that the U.S. government impose more targeted sanctions on Chinese officials and entities responsible for severe religious freedom violations; especially those within the United Front Work Department, the State Administration for Religious Affairs, as well as China’s public security and state security apparatus.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.