President Joe Biden promised to designate Kenya as a “Major Non-NATO ally” during a state visit by Kenyan President William Ruto on Thursday.

The upgraded status, which has never before been granted to a sub-Saharan nation, gives Biden a success to tout after a string of diplomatic disasters in Africa, as well as giving Ruto a jolt of prestige while he attempts to implement an unpopular and legally questionable decision to deploy Kenyan police to gang-ravaged Haiti.

Biden told Congress he wanted to grant Kenya the enhanced designation in recognition of its “many years of contributions to the United States Africa Command area of responsibility, and globally, and in recognition of our own national interest in deepening bilateral defense and security cooperation.”

“Kenya is one of the United States Government’s top counterterrorism and security partners in sub-Saharan Africa, and the designation will demonstrate that the United States sees African contributions to global peace and security as equivalent to those of our Major Non-NATO Allies in other regions,” he said.

At a joint press conference with Ruto on Thursday, Biden said the designation was the “fulfillment of years of collaboration.”

“Our joint counterterrorism operations have degraded ISIS and al-Shabaab across East Africa. Our mutual support for Ukraine has rallied the world to stand behind the U.N. Charter. And our work together on Haiti is helping pave the way to reduce instability and insecurity,” Biden said.

Armed gang leader Jimmy “Barbecue” Cherizier and his men are seen in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, March 5,2024. (CLARENS SIFFROY/AFP via Getty Images)

Ruto said on the latter point that he was determined to put Kenyan boots on the ground in Haiti because gangsters cannot be allowed to ruin the country.

“Gangs and criminals do not have nationalities. They have no religion. They have no language. Their language is one: to deal with them firmly, decisively, within the parameters of the law,” he said.

Kenya offered to lead a multinational peacekeeping force in Haiti last summer amid United Nations pleas for intervention. Haiti’s security situation began deteriorating rapidly after the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in July 2021. In March 2024, unelected Prime Minister Ariel Henry was effectively exiled from the country when a wave of gang violence erupted while he was visiting Kenya to negotiate the long-stalled intervention plan with Ruto.

Henry resigned in April, paving the way for a transitional council to appoint an interim government and plan for elections within two years. This removed a major stumbling block to intervention plans, since there were fears the Haitian people would reject foreign forces as an attempt to keep the corrupt and unpopular Henry in office forever.

Kenyan courts had previously blocked Ruto’s intervention plan by ruling that he lacked constitutional authority to deploy police forces on foreign soil. In March, before Henry resigned, he signed a “reciprocal agreement” with Ruto that seemingly removed some of the legal obstacles to intervention. The Kenyan opposition denounced the agreement as a stunt to circumvent the law and vowed to file more lawsuits.

Some Kenyan officials said Henry’s resignation would make the police deployment impossible because Haiti no longer had even the pretense of a “political administration.” The transitional council appointed an interim president and prime minister at the beginning of May, which seemed to address that objection.

Ruto kept pushing for the police deployment, and it seemed like it might finally happen this week, but the planned flight from Nairobi to Haiti was postponed without explanation on Tuesday. Two hundred Kenyan police officers were reportedly waiting to board the plane when the flight was canceled.

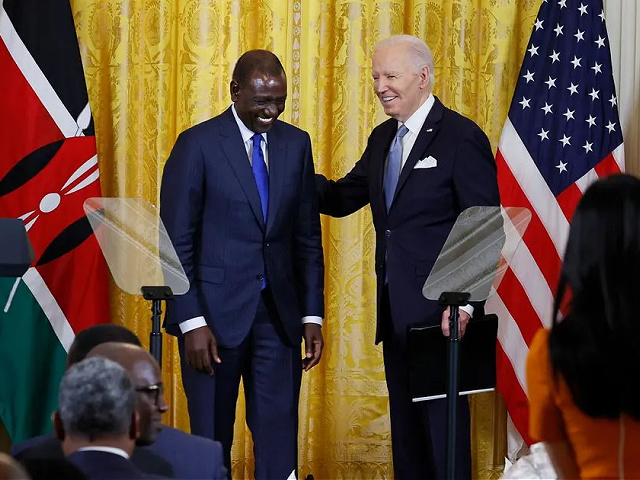

U.S. President Joe Biden and Kenyan President William Ruto hold a joint press conference in the East Room at the White House on May 23, 2024, in Washington, DC. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Ruto, who by that point had arrived in Washington for his state visit, insisted the intervention would still proceed. Kenyan officials said delays in the procurement of equipment for the intervention force, including armored vehicles and medical helicopters, could push the mission back to June or later.

A U.S. official added there were complications in the rules-of-engagement negotiations between the Haitian transitional government and Kenya and, until that agreement was signed and submitted to the U.N. Security Council, the deployment could not begin.

“They are running into some stark realities in terms of equipment logistics,” a U.S. congressional aide told the Miami Herald. A six-member delegation from Kenya reportedly found Haiti could not guarantee their own security, let alone the security of hundreds of police officers.

The delay was an embarrassment to Biden and Ruto, who had mutually hoped to announce Kenyan boots on the ground in Haiti before Ruto left Washington. Biden has pledged about $300 million in support for a multinational Haitian force that does not exist, some of it procured with dodgy invocations of presidential emergency powers, raising strenuous objections from congressional Republicans.

“Prior international interventions over a long, long period of time in Haiti had been dismal failures, leaving the Haitian people worse off than before,” noted one of those Republicans, Sen. Jim Risch of Idaho.

“We can’t use U.S. taxpayers dollars to support an open-ended, poorly conceived mission in a country plagued by extreme gang violence and political instability without some kind of assurances that things are going to be different this time,” Risch said.

Biden, meanwhile, is reeling from a series of humiliations in Africa, which he declared a diplomatic priority early in his administration.

American forces have been kicked out of Chad and Niger, depriving the U.S. of vital counter-terrorism resources in the dangerous Sahel region. Biden’s withdrawal from Niger leaves behind a $100 million airbase that could well end up in the hands of incoming Russian forces, along with an undetermined amount of American equipment that might need to be left behind.

Supporters of Deputy President and presidential candidate William Ruto celebrate his victory over opposition leader Raila Odinga in Eldoret, Kenya, Monday, Aug. 15, 2022. (AP Photo/Brian Inganga)

Kenya has been much more cooperative with U.S. security and foreign policy goals, although its gigantic debts to China might limit how far it can be drawn into the American orbit. Granting Major Non-NATO Ally status (MNNA) extends certain benefits to Kenya, including greater latitude to purchase certain military technologies and secure U.S. loans, but it does not include any security guarantees.

The BBC noted that Biden is rolling some big diplomatic dice by cozying up to Ruto, who was charged with crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for violence after Kenya’s 2007 election, although the case later fell apart and Ruto is clearly eager to burnish his image as an international statesman. Human rights organizations have also cast a skeptical eye at the record of the Kenyan police and wondered if they are the best choice for leading an intervention in Haiti.

U.S. Ambassador to Kenya Meg Whitman told the BBC that Ruto and Kenya are the administration’s best bets for building influence in Africa, and Kenya’s potential to become a technology hub makes it worth the gamble.

“If you really want to lean into Africa, then who would be the right choice to come to a state dinner? Kenya has been a long-standing 60-year ally of the United States. It is certainly the most stable democracy in East Africa. President Ruto has stepped up and he’s a real leader,” she said.