The arrest on Saturday morning of the Sinaloa cartel’s front man, Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzmán, was not just a victory for the Mexican government. It foretold the end of the mafia-esque era of “old school” drug cartels that characterized several decades in the history of Mexican drug trafficking. The future narco landscape is now littered with roughly 80 smaller gangs and mini cartels that are fighting to the death for their share of the multi-billion dollar illegal drug business.

Cartels like the Sinaloa Federation formerly run by El Chapo were a family business in the 1980s and 1990s. All of them go back to one main drug trafficking organization in Mexico known as the Guadalajara cartel. It was split up into a few pieces in 1987, and its remnants still exist today as the Tijuana, Juárez, and Sinaloa cartels. The Gulf cartel in the northeast corner of Mexico developed independently at around the same time frame, but is a shadow of its former self, much like the Tijuana and Juárez cartels.

The two bulwarks remaining today are Guzmán’s organization and Los Zetas, a group that started out as a private army for the Gulf cartel, but then went independent in 2010 as drug traffickers and bloodthirsty killers willing to target innocent people in their greedy quest for profits. But even Los Zetas, as large and powerful as they are, have started to show some major cracks, and the Sinaloa Federation has been hit particularly hard by the Mexican government in recent weeks.

These events have led to a new evolution of drug trafficking organizations. The barriers to entry into the drug business have been lowered, and we’re seeing a preponderance of smaller criminal groups that are more fluid and flexible, able to switch up alliances more quickly based on their business interests. They’re half mini cartel, half gang, and increasingly more elusive from the Mexican government. They are also growing in number, and that spells trouble–the more competition for territory and drug profits, the more violence that tends to spring up.

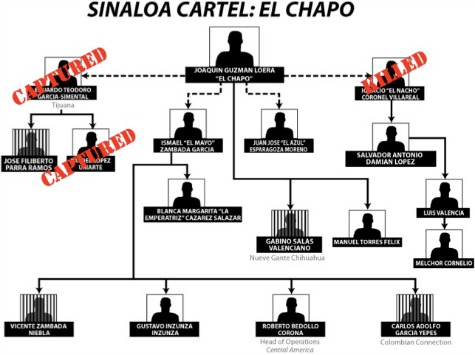

And the potential for violence isn’t limited to battles between these groups; any time a kingpin is killed or captured, higher-level members within that organization start eyeing the prize and evaluation their options for moving up the ladder more quickly, through murderous means if necessary. The Sinaloa Federation is pretty firmly organized at its highest levels, and Guzmán likely had a solid succession plan for his number two, Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada to take his place. However, the Federation is just that–a loosely knit consortium of smaller trafficking groups that will exploit any sign of weakness to break away from their parent organization and become a new rival.

The next few weeks will tell how the Federation will survive this transition, and what–if any–new mini cartels will arise as a result of El Chapo’s arrest. One thing is for certain: regardless of who’s in charge, the blood, the money, and the drugs will continue to flow.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.