A mere parent or citizen–even a college professor who sees the effects of college unready freshmen every year–might lament that the new Indiana college- and career-ready draft standards are simply copied-and-pasted Common Core being sold by the political and educational establishment as something new and wonderful.

Indeed, one could have left the Indiana Statehouse last week either exceedingly incensed or depressed after watching a 24-member Educational Roundtable, chaired by Governor Pence, vote to approve the new draft standards after listening for almost two hours to a panel of educrat “experts” offer nothing but talking points about “research based practices,” “standards evaluation processes,” and “stakeholders involved in the process” (of creating standards), and the “depth of the Indiana process”–yet without a single intelligent word concerning genuine learning being uttered. One could also have come out of that meeting thinking that the people doing the talking and deciding the fate of Indiana’s students have no idea what those standards even mean nor what effects they will have on the classroom; in short, they could not explain the standards to save their lives. That was my initial reaction.

But that was before I learned about the Pence Index. The Pence Index is a game changer. Don’t ask me how I found out about it. I know someone on the inside of the process, who leaked the true means of evaluating the standards. Simply put, the Pence Index is the imperceptible but crucial difference between six of one and half a dozen of another. The Pence Index may or may not work outside of the state of Indiana. It has yet to be field-tested; but within Indiana, it is solid gold.

Here is how it works. First, you, as governor, assemble several teams of career educators, all of whom are part of the education establishment. Then you tell them to revise the existing state standards, which are the Common Core. While they are doing that, you speak in very general terms about how important it is to have higher standards in a “twenty-first-century global economy.” When that phrase grows a little stale, you use “college and career readiness.” Don’t forget “raising the bar,” and needing “to move forward, not backward.”

It is important never to discuss an actual book that a child might read and enjoy. What do you know about books? You’re just a governor. Books are for the teachers in local schools to decide, who will intuitively know how to do that, having come out of the progressive schools of education that have done such a good job of training teachers over the last forty years.

Nor will these career educators feel in any way threatened or coerced by the prospect of standardized exams (yet to be created) whose contents will assuredly require students to know the catechism of environmental friendliness more than Mark Twain.

And, of course, we can always rely on school superintendents, who are paragons of erudition, constantly quoting poetry and never hiding behind empty phrases such as “life-long learners” and “standards-based outcomes.”

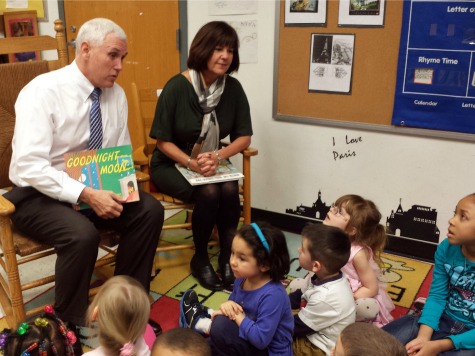

Since a picture is worth a thousand words, it is essential that you, as governor, frequently appear in the newspapers surrounded by lots of school children dressed in red, white, and blue.

Finally, you must employ the magic incantation–“Hoosier standards for Hoosier students”–as often as possible.

While all this is taking place in the public eye, behind the scenes the so-called technical team must copy, er… rewrite each standard. A week later their BFF’s on the evaluation team assign each standard a number between one and twelve, with six (not to be confused with half a dozen) being the minimal number for a standard to meet the unspecified criteria for sufficient distinction between Common Core and Hoosier-Gold. Almost all the “revised” standards pass. In addition, while you have invited a few national advisors to comment on the draft, you don’t pay any attention to the ones who show its proximity to Common Core because they’re not, well, Hoosiers and thus can’t understand the Pence Index.

Then you have a big meeting at the Statehouse the Monday after Easter, after the state has had all of three or four days–including Easter Sunday–to look at the new standards. Much of the meeting is taken up by one of the national evaluators asked to join the panel. She flatters Indiana for such “a rigorous and systematic approach” to adopting standards. This person, whose degree is from Berkeley and who works in Washington, D.C., is not a Hoosier. She is normally hired to help other states and districts “navigate the path” to Common Core. Inside Indiana, however, her job is to praise the process that led to standards wholly different from Common Core.

Other members of the process comment on the virtues of the process. The word process is used eighty times (I counted), which reveals what a great process it was that brought Hoosier standards to Hoosier students.

Unfortunately, there is not enough time during this roundtable discussion to talk about any of the standards themselves and how they might manifest themselves in the classrooms of Indiana. Nor is there time to address how the many parental concerns over the Common Core are being addressed in the new standards. Will students still have to use fourteen steps to answer a simple multiplication problem? Will younger students read any works of classic literature, such as the stories of Hans Christian Andersen, who is not mentioned in the Common Core? Will non-fiction almost wholly supplant fiction by the senior year of high school? Will the informational or non-fiction texts urged by the Common Core be politically biased, such as articles on Obamacare? Will students be required, in the name of media and computer literacy, to be behind computers for five or six hours of every day? Will Hoosier students be reading The Bluest Eye? Alas, so many questions those parents have, and so little time to answer them–or even bring them up!

How, then, would the Pence Index work in practice? Here is an example taken from both the existing Indiana Standards (the Common Core) and the new draft standards:

Read common high-frequency words by sight (e.g., the, of, to, you, she, my, is, are, do, does). (Common Core English, RF.K.3c, p. 16)

Read common high-frequency words by sight (e.g., a, my) (Indiana ELA, K.RF.4.4, p. 10)

Now some chronic worriers, especially home-schooling parents and those who have their children in these new-fangled classical schools, might object to the phrase “by sight” and contend that this is simply the failed whole language method rearing its ugly head–in the category labeled phonics, no less. They might point out that students should learn each word by its distinct phonograms, not “by sight”; otherwise they are simply memorizing pictures, not breaking down words.

These “worriers” might assert that whole language is what has led to chronic partial literacy in this country and outright illiteracy. They might try to explain to Governor Pence that is why so many Hoosier students showed up to Hoosier colleges last year needing remediation, a statement he likes to make in support of these new standards. They might take seriously the study conducted by the National Council on Teacher Quality that showed that the vast majority of education schools in Indiana neither offer nor require any meaningful phonics instruction.

Such critics reveal their complete ignorance of the Pence Index. Clearly there are fewer examples of sight words in the Indiana standard versus the Common Core standard. Clearly Hoosier teachers will know what sight words are most suitable for Hoosier students. Besides that, a person cannot simply “cherry-pick” standards. In the case of this particular standard, one must pay attention to its articulation.

Articulation is a very important concept in standards production. It refers to how a standard changes and develops across different grade levels. In this standard, sight words are continued up through second grade (at least, that’s as far as we are told). But by third grade, the standard becomes much more rigorous:

Read grade-appropriate words that have blends (e.g. walk, play) and common spelling patterns (e.g., qu– . . .) (Indiana ELA 3.RF.4.4, p. 10)

The standard just below this one, apparently for the fourth grade, according to the number scheme, is even more rigorous.

Know and use more difficult word families when reading unfamiliar words (e.g., –ight) (Indiana ELA 4.RF.4.5)

Now in most genuine phonics programs the words “walk” and “play” and “quit” and “queen” and “light” and “right” and even “fright” would be learned by the end of kindergarten, or at the very latest first grade by weaker readers; but, by golly, if Hoosier career educators want such words to be considered “grade appropriate” and “more difficult” and even “unfamiliar” words in the third and fourth grades, the Pence Index tells us unfailingly that these are Hoosier standards for Hoosier students!

So what if a Hoosier first-grader cannot read the sentence, “He walked into the night and lit a light, and all was quiet.” The kindergarten standard gets a Pence Rating of 7 and the latter two score 10 and 12 on the Pence Scale. A home run!

Accordingly, the technical and evaluation teams rightly ignored the national evaluator who told them that standards like these are “a recipe for semi-literacy at best” and “can only result in delayed reading, bad spelling, and a general confusion about English orthography.”

We could continue to work through the new Indiana Draft ELA Standards in order to unveil the marvels of the Pence Index. Of course, such a discussion is impossible to achieve, however, during such a necessarily rushed process. There is a dark cloud on the horizon, though, which it pains me to unveil.

Based on a few secret trials, it turns out that while the Pence Index does wonders in distinguishing proximal values, that is, the difference between six of one and a half dozen of another, it actually collapses or hides substantial differences between words, concepts, and even personages. When any technical team is required to calculate the difference between the words politician and statesman, to cite one random example, they only come up with a Pence Score of 3, well below the necessary 6. When the names Socrates and Glenda Ritz were evaluated, they returned a score of 2. Socrates was, of course, the Athenian whose probing questions led to the birth of philosophy; Glenda Ritz is the predictably platitudinous Superintendent of Public Instruction for Indiana who has not asked an illuminating question in forty years as a career educator.

A similar trial was performed using the names Arne Duncan and Sir Isaac Newton, which returned a score of 1. More disturbingly for the governor’s political career, a test was conducted using the names Ronald Reagan and Jeb Bush. The Pence Index rendered the lowest possible score of .01. In other words, on the Pence Scale, there is no difference whatsoever.

Terrence O. Moore is the author of The Story-Killers: A Common-Sense Case Against the Common Core. He is a professor of history at Hillsdale College and helps start classical charter schools around the country.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.