On the Menu

There’s an old joke: If you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu. That is, if you aren’t a player in the process, then you’re the one being played.

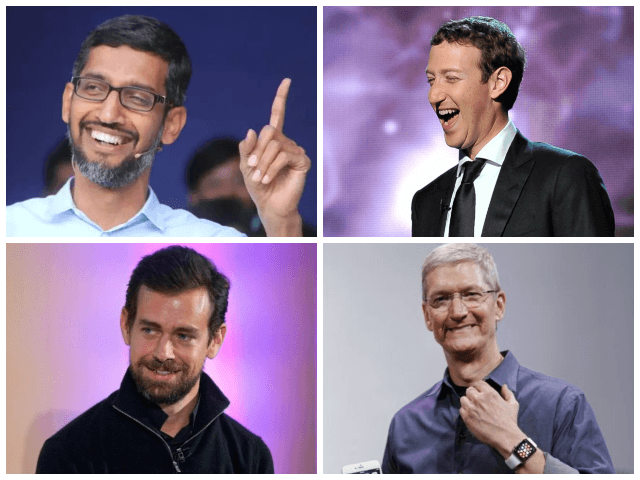

Just in the last three months, Americans have been played by Big Tech. Specifically, the Tech Lords have a) suppressed the Hunter Biden story, b) de-platformed Donald Trump, and c) mostly wiped out Parler, a “free speech” rival to Twitter. If these sorts of high-handed actions become the norm, then what will become of American politics? What of American freedom?

Speaking on Fox Business on January 15, Allum Bokhari, who for five years has tirelessly chronicled these developments for Breitbart News, decried “the merging of the political power of the Democratic party with the unchecked corporate power of Big Tech giants.” (The Washington Post counts at least 10 tech platforms that have “banned Trump and his allies”–with probably more to come.)

So what should be the conservative response? How do Republicans protect themselves from one-sided treatment? From media bias of a whole new kind?

The old libertarian mantra, Let the free market decide, no longer seems adequate. And to that point, the case of Parler is instructive. Rather than just complain about social-media bias, Parler—launched in 2018 with the declared goal of creating a “free speech” alternative to Twitter—sought to apply free-enterprise principles to giving consumers a choice.

Indeed, in the wake of Twitter’s banning Trump earlier this month, Parler was gaining momentum. On January 9, TechCrunch headlined, “Parler jumps to No. 1 on App Store.” As the tech site detailed, “Parler saw approximately 210,000 installs globally on Friday 1/8, up 281% from approximately 55,000 on 1/7.” All this growth, we might add, came after a strong 2020, a year in which the Parler app boasted 8.1 million installs.

Then the hammer came down. On January 11, Amazon shut down its cloud services for Parler, while Apple and Google booted Parler’s app from their app stores. Surveying this swift hammer-down, a fearlessly iconoclastic left-wing journalist, Glenn Greenwald, wrote:

If one were looking for evidence to demonstrate that these tech behemoths are, in fact, monopolies that engage in anti-competitive behavior in violation of antitrust laws, and will obliterate any attempt to compete with them in the marketplace, it would be difficult to imagine anything more compelling than how they just used their unconstrained power to utterly destroy a rising competitor.

And while the social media giants ramp up their purge of conservatives, repressive and threatening regimes like China and Iran are free to continue using these platforms. On January 16, Breitbart News added a new datapoint on hypocrisy, when Alana Mastrangelo reported that Amazon blithely sells tee shirts that read, “Kill All Republicans.”

Interestingly, as of January 17, Parler was back on line—sort of. A message from CEO John Matze spoke of “technical difficulties,” and expressed the hope that “civil discourse” could resume “soon.” Meanwhile, later reports indicate that Parler hopes to be online again, “by the end of the month.”

It’s encouraging that many thoughtful Americans, across the spectrum, have been troubled by this brandishing of unaccountable corporate power. For instance, a maverick centrist, Michael Lind, was moved to write:

Whatever one thinks of Donald Trump, the decision of Twitter and Facebook to lock him out of his accounts, and the mass purge of moderate conservatives as well as right-wing militants that was then carried out by numerous digital firms, including Amazon, Apple and Spotify, was a shocking demonstration of where real power lies in the twenty-first century United States.

Meanwhile, a little to the left of Lind is Bari Weiss, who quit the New York Times last year over politically correct censorship concerns; she is no fan of Trump, and yet she writes that she is disturbed “that Twitter can ban whoever it wants whenever it wants for whatever reason.” She adds her concern “that all the real town squares have been shuttered and that the only one left is pixelated and controlled by a few oligarchs in Silicon Valley.”

Further over to the left, the American Civil Liberties Union jumped in; senior legislative counsel Kate Ruane told The Blaze: “It should concern everyone when companies like Facebook and Twitter wield the unchecked power to remove people from platforms that have become indispensable for the speech of billions.”

Meanwhile, tech writer Alex Kantrowitz foresees the same censorious tech reaper coming for other platforms, too, including Substack, Spotify, and Clubhouse. Indeed, every platform—including those most favored by conservatives (sometimes now called “Parler refugees”), such as Gab, Caucus Room, and MeWe—is vulnerable.

In response to these once and future suppressions, many say that the right answer is to go underground, hiding in encrypted apps, such as Signal or Telegram. That option will seem tempting to some, and yet those going incognito should realize that they can still be tracked. After all, the makers of the apps will always know, whether they admit it or not, how to monitor users—it’s a product, after all, that they made—and so, too, will others, in both the private and public sectors.

Meanwhile, activists have filed a lawsuit against Apple, seeking to force it to ban Telegram from its app store, just as it did Parler. And the New York Times is on the warpath against these encrypted apps, warning readers that “far-right groups” are already using the apps to plan “violent rallies.” So if that’s the current media environment, the Biden administration, as well as like-minded state attorneys general, won’t have any trouble commanding the political, legal, and technical mojo to keep close tabs on apps that can be said to traffic in “hate.”

Moreover, since the same apps can be used for obvious criminality, such as drug-running or child pornography, they and their secret ways simply aren’t going to be tolerated for long.

Let’s further remember that all these apps and websites depend on the internet, which is now dominated by a few giant companies, such as AT&T and Verizon. So if authorities feel the need to, they’ll simply close down the net to forbidden users, leaving the cleverest encryption program high and dry.

Of course, we shouldn’t underestimate human creativity, and so there will always be someone cooking up some new scheme for secrecy and anonymity in cyberspace, and some of these schemes will work—at least for a while. Yet if communication is driven deeply underground, then, by definition, it’s not mass communication. And mass communication is the essence of democratic electoral politics; pols and parties must be able to reach voters, and vice versa.

We can further add: If mass communication is necessary for politics, then politics is necessary to secure mass communication—but only if the public, through politics, is willing to actively defend its right to free speech. (This point also holds true for cable news, now that CNN has launched something of a campaign to de-platform Newsmax and One America News from their cable carriers, and, yes, perhaps also ban Fox News.)

Fortunately, the idea of the public’s flexing its muscles to guarantee its rights in public space is deeply engrained in our history. So this would be a good time to rediscover that history.

The Public Thing and the Public Space

Our word “republic” comes from the Latin res publica—literally, the public thing. As Abraham Lincoln called it, “government of the people, by the people, for the people.”

With this vision of the public thing in mind, we should realize that even in a private-enterprise economy, some things are destined to be held as public trusts, even if they are owned privately. These common things include roads and bridges, of course. Another common thing is the air that we breathe; we have a common-law right to clean air, and a common-law duty not to dirty it.

Moreover, the air around us has another value; it is the medium though which we communicate: by visual sight, by spoken voice, and, also, of course, by wireless telecommunication. As we can see, by virtue of being citizens of this republic, we have a stake in how communications through the common atmosphere are managed.

From this idea of commonality, we arrive at the concept of the common carrier. Those two words are a specific term of legal art, reaching back to Roman times. In ancient days a common carrier was, say, the owner of a bridge, or a ferry, or an inn. In return for the right to operate these amenities—and in turn to be protected by the full force of the law—the operator had a duty to treat all paying customers fairly.

In the late 18th century, the famed English jurist William Blackstone elaborated on the expanding category of common carriers:

There is also in law always an implied contract with a common inn-keeper, to secure his guest’s goods in his inn; with a common carrier or bargemaster, to be answerable for the goods he carries; with a common farrier, that he shoes a horse well, without laming him; with a common taylor, or other workman, that he performs his business in a workmanlike manner.

In the summarizing words of Tulane University law professor Charles K. Burdick, writing back in 1911, “From this we see that a person, by holding himself out to serve the public generally, assumed two obligations—to serve all who applied; and, if he entered upon the performance of his service, to do it in a ‘workmanlike manner.’”

Of course, the definition of a common carrier has continued to evolve with the times. Today, we realize that the internet is at the heart of modern life; it’s almost impossible to live or work anymore without being online—and this reality has been accelerated, of course, by the virtualization required in this Covid-19 age.

So it’s little wonder that Big Tech has become even bigger: It is literally at the crossroads of our lives, exacting tolls and fees—including tariffing the value of our personal data—for everything we do. We can accept that the tech companies have a right to earn a profit, but we should also realize that they do not have a right to abuse their power.

Indeed, we should realize that the tech companies are, effectively, common carriers. That is, they should have all the rights, but also the responsibilities to the public, that attach to common-carrier status. To be sure, this reality of common-carrier status is an evolving understanding, although forward-looking Republicans, such as Rep. Matt Gaetz of Florida, are on board with the concept.

In fact, to reinforce the point about Big Tech’s common-carrier status, we can add that even now, rich as the tech companies are, their future growth is partially dependent on the further building out of public infrastructure. This point was made well by Sen. Roger Wicker of Mississippi, the top Republican on the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee. Addressing the issue of censorship, Wicker told Fox News that if the American people were being asked to finance broadband expansion as part of a new-style infrastructure agenda, then they have the right to expect that the internet will be managed fairly:

We’re about to spend billions of dollars building out broadband and making it easier for these people to connect with Americans. I think we have to ask, don’t they have some obligation to make sure that they don’t stifle information and stifle free speech?

Wicker is correct. The American people shouldn’t be paying for things that discriminate against them. And in fact, Joe Biden has big plans for “universal broadband.” So we can see the risk that Uncle Sam will pay for the Tech Lords to further lord it over us.

A Place at the Table

So how do we make sure that the American people are treated fairly in this space—which is, as we have seen, public space? How do we hold the Big Tech companies to their obligations as common carriers?

The broad answer to these questions is simple: The American people need a place at the table. As we have seen, if the people are not at the table, they’ll be on the menu.

One possible answer is a Federal Platform Commission (FPC), overseeing Big Tech’s common-carrier responsibilities; and this FPC could be an outgrowth of the existing Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

So would an FPC be more Big Government? Maybe, but sometimes the public interest requires that Big Tech be matched by something equally big—something that is accountable to voters, in a way that Twitter, to cite just one tech company, is not currently accountable.

It’s worth noting that, by law, the FCC must allocate at least two of its five commissioner slots to the Republican Party—and that’s two more seats at the table than the GOP has at any company in Silicon Valley. Moreover, the entire FCC is all about due process and transparency; sure, it’s kludgy with bureaucrats and lobbyists, and yet at least the people have a voice—and once again, that’s more leverage than the people have with the likes of Jack Dorsey, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerberg.

(Amusingly, on January 21, Axios reported that Facebook has turned the case of Trump’s de-platforming over to its supposedly independent “Oversight Board,” which will make a recommendation as to Trump’s ultimate status on the platform. We can note the sort of strange mimicry here, as the private sector imitates the public sector: Facebook has set up its own “agency,” offering its own kind of “due process.” It would be far better if the American people, working through elected and appointed public officials, were in charge of a real due process.)

So the goal of the FPC would be to guarantee that decisions about censoring, de-platforming, and algorithmically suppressing cannot be made in isolation from the public interest. In other words, the FPC would force the big tech platforms to fulfill their duties as common carriers; as Tulane professor Burdick would have put it, “to serve all who applied.” Yes, the companies could still impose standards of decency and legality, but those standards would have to be applied fairly and transparently.

As it happens, back in 2018, the idea of an FPC was raised here at Breitbart News, and this author raised the idea again last June. And yet today, in the wake of Big Tech’s purges, the need for some kind of oversight is all the more evident.

Of course, many other ideas for restraining the power of Big Tech are floating around, including antitrust enforcement and the abolition of Section 230. Perhaps all these ideas should be considered, and yet we should never lose sight of the need for public oversight.

If the people are vigilant about protecting their rights and exercising their democratic powers, they will be at the table—and not on the menu.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.