The Power Game Is a Numbers Game

The final battle of the 2020 elections—the two senatorial runoff elections in Georgia—comes to a close on January 5. And yet as we shall see, the Democrats’ patient preparations for the battle have been going on for years.

An indication of the work that’s been done came on December 18, when Stacey Abrams, the Democratic nominee for governor in 2018, tweeted that a record total of 7.7 million Georgians were now registered to vote. Abrams made no mention as to how those folks, especially new registrants, might be inclined to vote—and Georgia doesn’t register by party—and yet she credited a variety of Democratic and left-wing groups for the registration surge, including the New Georgia Project, Black Voters Matter, and the Georgia chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Interestingly, since October 5, 76,000 new Georgia voters have been registered. These new voters were not eligible to vote on November 3, but they will be eligible to vote on January 5. And of these newbies, more than half are under the age of 35. For perspective, Joe Biden, who carried the national youth vote handily, won Georgia by 11,779 votes.

As Breitbart News reported on the 18th, Abrams told CNN, “1.2 million absentee ballots have been requested thus far, and just to put that into context, 1.3 million were requested for all of the general election”—that is, absentee balloting for the January 5 runoff has already nearly exceeded absentee balloting for the November 3 election. And just on December 24, she tweeted:

57,429 Georgians who already cast a ballot in the Jan 5 runoffs did not vote at all in the presidential election. Half or more are people of color. Thanks to all who registered fellow Georgians and to all who are mobilizing voters.

Then on the 28th, Abrams, who seems to have a standing invitation to appear on CNN whenever she wishes, used her appearance on the cable channel to raise the specter of “voter suppression”–which Republicans interpret as one more tool that Democratic pols use to drive Democratic turnout.

And on January 1, Georgia authorities announced that early voting had hit three million. As the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported, turnout in mostly White rural areas was lagging; Meanwhile, Black voters, who generally support Democrats, made up a higher portion of voters so far than in the presidential election.

We can plainly see, of course, that Abrams is focusing on Democratic voters—with an eye to not only the upcoming elections this month, but the midterm elections in 2022, when it’s expected that Abrams will make another run for governor.

Abrams lost her bid for the governorship in 2018, and thereafter, in the eyes of some, she became a figure of ridicule over her refusal to ever concede that she had lost; in the meantime, she continued to focus—and fundraise—on voter registration and turnout. For instance, back on May 29, 2019, Karl Rove wrote in the Wall Street Journal:

Like P.T. Barnum, Ms. Abrams puts on an entertaining show that’s richly rewarding—for herself. She creates nonprofits with noble-sounding names, hires herself, and fills the payroll with campaign staffers who enjoy paychecks between elections. Before the 2018 contest, her perch was a voter-registration group called New Georgia Project. Now she has two nonprofits. One is Fair Fight, which files lawsuits and attacks Gov. [Brian] Kemp. The other is Fair Count, which encourages her supporters in Georgia to fill out census questionnaires. But she gave away their real purpose, explaining: “We can win this fight long-term by changing the structure of power.” That means putting her in office.

In fact, Abrams is, indeed, all about “changing the structure of power.” And whether or not she herself ever gains office, she has had an effect on statewide politics: Underneath the optics of her electoral defeat have been the tectonics of her drive to register more voters.

Democratic Senate candidate Raphael Warnock bumps elbows with Stacey Abrams during a campaign rally with U.S. President-elect Joe Biden at Pullman Yard on December 15, 2020, in Atlanta, Georgia (Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

To illustrate her impact, we might recall that back in 2014, the Democratic nominee in the Georgia gubernatorial race received 1.144 million votes. In 2018, Abrams, as the nominee herself, received 1.923 million votes—a nearly 69 percent increase. Of course, she still lost that race, and yet she cut the GOP victory margin from more than 200,000 votes in 2014 to barely more than 50,000 votes in 2018.

Moreover, in 2020, the numbers showed outright success for the Democrats. Turnout for Democrat Joe Biden surged nearly 32 percent, compared to Hillary Clinton’s vote in 2016, while in the meantime, turnout in 2020 for the Republican nominee in both years, Donald Trump, rose less than 18 percent. Thus Biden carried the Peach State, and, of course, the Republican senatorial candidates, both incumbents, were forced into runoffs.

In the wake of this year’s voting, Abrams has been getting more respect. Typical of the new tone was this headline in the November 6 Financial Times: “Stacey Abrams credited for mobilizing black voters in Georgia.” The newspaper quoted an Abrams lieutenant, LaTosha Brown, founder of the Black Voters Matter Fund, saying that the election results were the culmination of years of organizing:

We know our community. It’s going to take the churches, it’s going to take the civic groups, it’s going to take the activists, it’s going to take the organizers, it’s going to take the businesses. We’ve shown that when you invest in people on the ground, these are the results that you get.

Of course, it’s always an interesting question as to who exactly is paying for all of this activism, and we’ll get to that later. Yet for the moment, suffice it to say that Democrats in Georgia are playing a strong game. That is, before the ballots are counted, they are ginning up the total of potential ballot-casters.

(Some will ask, of course, Is fraud involved in running up these numbers? And the answer is that, as we’ve been reminded these past few weeks, fraud is easier to allege than to prove—and furthermore, to have any effect, fraud allegations must be proven. And the adducing of proof represents its own kind of patient and careful challenge.)

In the meantime, the Democrats’ strategy seems to be bearing fruit: This was the lead headline in Politico on December 30: “Strong early-vote turnout gives Dems hope in Georgia runoffs: Democrats are encouraged by stats that show their voters are overperforming with early voting set to conclude later this week.” As the article detailed, some 2.3 million Georgians had already voted–a record total. And while we won’t know for sure which candidates are getting the benefit of this turnout till we know the election results, Abrams and her allies are obviously targeting Democratic voters.

So for now, let’s borrow a phrase from the military: Georgia Democrats are “shaping the battlefield.” That is, they have been thinking ahead and have been setting the terms by which elections will be waged. And the shaping is all about turnout. We can recall that in the run-up to the November 3 balloting, judges and others were changing the rules on voting–typically, extending voting deadlines. In the meantime, Democratic governors were doing things like issuing executive orders to mandate mailed ballots. These actions, typically without the consent of a legislature, were also efforts to shape the political battlefield.

As for the upcoming balloting in Georgia, we should stipulate that such shaping does not guarantee that Democrats will win one or both of the runoff elections, but careful anticipation of the fight does mean that they are setting the tempo of the political combat: It’s all about who can convert latent votes into actual votes.

In other words, this shaping of the battlefield is about plans made in advance of the actual battling.

Sun Tzu’s Wisdom and the Peach State

Some 2,500 years ago, the value of premeditation in advance of the fight was argued by the Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu, writing in his classic treatise, The Art of War:

Thus it is that in war the victorious strategist only seeks battle after the victory has been won, whereas he who is destined to defeat first fights and afterwards looks for victory.

Sun Tzu is saying, Winners make the plan first, and then start fighting. Losers start fighting, and then seek a plan–but by then it’s too late.

Sun Tzu’s advice makes obvious sense, and yet at the same time, we can see that it’s hard to apply it in practice. After all, in peacetime, the temptation is to avoid thinking about war–after all, it’s an unpleasant subject Yet Sun Tzu insists that the wise general must always be thinking about war, and planning for victory.

In this vein, we might think of the British poet A.E. Housman, who, having lived through World War One, was a gloomy realist. In one of his poems, he contrasted himself to those who thoughts were “light and fleeting.” By contrast, Housman wrote of himself, “Mine were of trouble/ and mine were steady/ so I was ready/ When trouble came.”

Sun Tzu would second Housman’s point: Be ready when trouble comes. When the trouble does start, “the fog of war” sets in–that is, the inevitable confusion that comes from swirling events amidst violence. In the heat of battle, it’s planning in advance–including planning for more firepower–that makes for victory.

And the same is true with campaigns: The strategist can never know what crazy thing will happen on the campaign trail, and so that’s all the more reason to identify loyal voters and mobilize them to the polls, so that the ups and downs of the spin cycle don’t matter as much. We can see: Get Out the Vote, if done right, matters more than Twitter.

Recently, Sun Tzu’s ancient wisdom was restated by Rep. James Clyburn of South Carolina, the No. 3 Democrat in the House. As the New York Times reported on January 24, 2019, just after the Democrats had recaptured the House in the 2018 midterms, Clyburn was feeling martially philosophical at a private meeting of House Democrats. Here’s how the Times set the scene when Clyburn introduced Rep. Nancy Pelosi, who had just reclaimed the speaker’s gavel:

“Victorious warriors win first and then go to war, while defeated warriors go to war first and then seek to win,” Mr. Clyburn said. Turning to Ms. Pelosi, he said, “Thank you for winning for us. Now let’s go to war.”

Proper planning for victory is never easy, but it’s always essential. And as we shall see, the Democrats are good at both planning and shaping.

Big Data + Big Money = Democratic Victories in California

For decades now, Democrats have been using their not-so-secret weapon, Silicon Valley, to affect elections by deploying their advantages with tech and techies to shape the political battlefield. Their key is to win before they start fighting—and one way to win in advance is by drawing the lines in their favor.

Back in 1981, this Democratic edge became shockingly clear in California, when, in the wake of the decennial census, Democrats redistricted the Golden State to stunning partisan advantage. Yes, clever redistricting is is an old process—reaching back to an early 19th century Massachusetts politician, Elbridge Gerry, who gave his name to the line-sculpting art of “gerrymandering.” In that same spirit, in the 20th century, California Democrats used computers to help them gerrymander legislative districts in ways that had never been done before, thereby optimizing Democratic strength and minimizing Republican strength.

The results in California were dramatic. After the 1980 Congressional elections in that state, Democrats had held 22 House seats, while Republicans held 21—very close. And yet after the 1982 elections, using the slick new technique that we might dub “data-mandering,” Democrats held 28 House seats, while the GOP held just 17.

Since then, both parties have become adept at using big data to help with gerrymandering, resulting in grotesquely spidery districts across the nation; in 2014, a Washington Post reporter labeled the whole geeked-up process as “crimes against geography.”

Yet in addition to gerrymandering, newer kinds of computer-tech have been applied to politics. We’re probably all familiar with computer-driven microtargeting, which seeks to pinpoint each voter and entice his or her vote, based on personal information derived from available data sets. Once again, both parties eagerly engage in this process, and, interestingly enough, for a brief time, in the early 2000s, it seemed that the Republican Party had the microtargeting advantage.

Yet then the Democrats regained their advantage in tech-driven politics. One hinge moment came in 2008, when Facebook inadvertently allowed its “social graph”—that is, the data on its many users—to be tapped by Barack Obama’s presidential campaign. The partisan value of this tapping was little understood at the time, and it seems that Facebook, too, was caught by surprise. And yet the result of this ill-gotten data trove was an incalculable windfall for the Democrats. Then, in 2012, Facebook alums, joined by other Silicon Valleyites, made up Obama’s reelection campaign tech “dream team.”

More recently in California, the state government itself seems to have gotten into the game. Back in August, the Sacramento Bee reported that the state’s secretary of state, Alex Padilla, had allocated $35 million for a political consulting firm, SKD Knickerbocker, to craft a campaign for “Vote Safe California”—a new program, the goal of which was to “prevent, prepare for, and respond to the impacts of COVID-19 on the election and provide associated voter education and outreach.”

Interestingly enough, the company leans heavily toward the Democrats. As the Bee reported:

The firm is run by CEO Josh Isay, who ran Democratic Sen. Chuck Schumer’s 1998 campaign. Other notable employees include former Obama communications official Anita Dunn and Hillary Rosen, a longtime media figure who also worked with California Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein. On its site, the firm lists itself as supportive of Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, saying it is “proud to be a part of Team Biden.”

Okay, we get the picture.

More recently, on December 2, the Bee reported that the firm has invoiced the state for $34,221,672.17. Interestingly, it seems that Padilla and the secretary of state’s office might have gotten a little ahead of themselves in signing the deal; there’s now a question as to whether the state is even allowed to make the payment.

California Secretary of State Alex Padilla speaks during a news conference on May 24, 2018 in San Francisco, California. (Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

For its part, SDK Knickerbocker said it is “confident” that the secretary of state’s office “will make payment to us for the full amount owed under the contract.” Indeed, it’s hard to believe that the Democratic firm will walk away empty-handed.

In the meantime, on December 22, California governor Gavin Newsom named Padilla to be the Golden State’s new U.S. senator, replacing Kamala Harris.

Okay, so there’s plenty of political battlefield-sharing going on everywhere. Nevertheless, the hottest news on political battlefield-shaping is coming from Georgia.

Centers for Democratic Voting?

Two recent reports suggest more ways by which big money is shaping the political battlefield, in the Peach State and elsewhere.

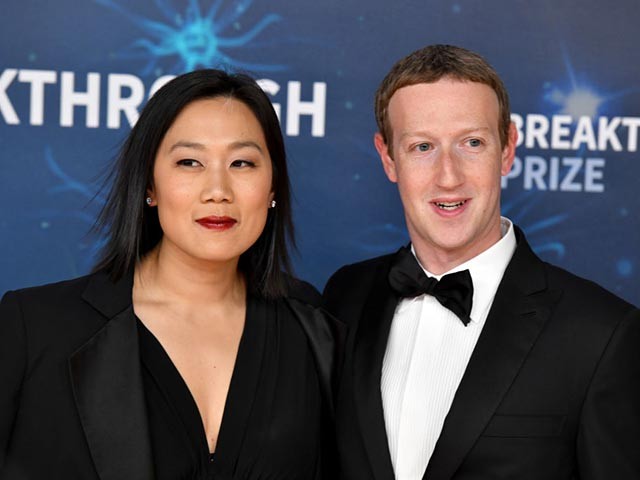

The first report, dated November 27 and titled, “Georgia Election Officials, a Billionaire, and the ‘Nonpartisan’ Center for Tech and Civic Life,” comes from the Capital Research Center (CRC), a well-known right-of-center investigative organization. CRC president Scott Walter takes note of a $350 million donation from Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, to the Center for Tech and Civic Life (CTCL); Walter speculates that the money may have been used to improperly affect the voting in Georgia.

According to Walter, the possible infraction is subtle in its design—and yet, at the same time, profound in its effect: Walter suggests that CTCL specifically targeted Democratic areas in Georgia, and elsewhere, for preferential help in voting, thereby generating more votes for Democrats. As Walter puts it, CTLC “re-granted [Zuckerberg’s] funds to thousands of governmental election officials around the country to ‘help’ them conduct the 2020 election.”

Summarizing CTCL’s efforts, Walter declares, “The picture is notably partisan.” He identifies 33 strongly pro-Biden counties in Georgia (out of 159) and finds that those 33 received the bulk of CTCL’s grants. As of now, his findings are preliminary assessments, nothing more, although they beg for a closer forensic investigation. Walter concludes:

Whether or not CTCL has crossed a legal line, the starkly partisan outcomes from its giving in the Peach State should lead the appropriate authorities in Georgia and Washington, DC, to determine just what has happened. Not only should CTCL be investigated for its adherence to nonprofit law, but the local election officials should also be asked many questions on their role.

Among the unanswered questions Walter poses: What methodology was used to determine CTCL grants? Which staff members were deployed? How were they recruited? What training did they receive? And so on.

All this is even more interesting, because CTCL is an avowedly nonpolitical operation: In fact, by law, it has to be nonpolitical, since it is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, and tax-exempt charities can’t play politics. Of course, in the meantime, donations to CTCL are tax-deductible, and for high-tax-bracket donors, that’s quite a benefit.

We should stipulate, to be sure, that Walter is a private investigator; he is not a prosecutor, let alone a judge or a jury. In other words, much remains to be known.

Yet in the meantime, we know this much for sure: The Zuckerberg-Chan donation made a huge difference to CTCL. According to Ballotpedia, in 2018, the most recent year for which data are available, the group enjoyed a total revenue of just $1.4 million—from givers including Google, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Rock the Vote, and the Women Donors Network. So Zuckerberg-Chan’s $350 million gift represented a 250-fold increase in the group’s fiscal strength.

Priscilla Chan and Mark Zuckerberg attend the 2020 Breakthrough Prize Red Carpet on November 03, 2019, in Mountain View, California. (Ian Tuttle/Getty Images)

So what else is there to know about CTCL? Well, for further perspective, its founder and executive director is one Tiana Epps-Johnson, who has worked in various left-wing organizations and received various left-wing honors, including a year as an Obama Foundation Fellow. And at CTCL, she’s hardly alone in her left-leaning beliefs.

The second report, dated December 14, from J.R. Carlson for the Amistad Project of the Thomas More Society, has already been covered by Breitbart News’s Michael Patrick Leahy, under the headline, “Report: Mark Zuckerberg’s $419 Million Non-Profit Contributions ‘Improperly Influenced 2020 Presidential Election.’”

As Leahy noted, this second report identified yet another group, the Center for Election Innovation and Research (CEIR), that also deserves scrutiny: It seems that CEIR received $69.5 million from Zuckerberg and Chan. And all that money—$419.5 million, total—according to Carlson and the Amistad Project, seems to have “improperly influence[d] the 2020 presidential election on behalf of one particular candidate and party” by creating “a two-tiered election system that treated voters differently depending on whether they lived in Democrat or Republican strongholds.”

We might add that Breitbart News has published three other articles on all this supposedly nonpartisan money—sample title: “The Greatest Electoral Heist in American History”—raising still more questions about these outfits’ activities.

To be sure, these are only allegations, and they will no doubt be further investigated—unless, of course, the Democrats win both Senate seats in Georgia, in which case, having regained their chairmanships, they will likely shut down any possible investigations. (And we shouldn’t expect much curiosity from Joe Biden’s Justice Department.)

Yet even as we hope that the fact-pattern can be established, we can already see this much: The Democrats have invested a lot of time, money, and computer-smarts into shaping the political battlefield—and it has paid off.

Republicans will have to catch up. Or else.

Numbers Matter

In any election year, anything to do with voting and vote-counting is of intense interest. And yet in 2020, we were reminded that even minute changes in vote totals can swing a state—and so swing the nation. This past November, a shift of only 33,000 votes—distributed across Arizona, Georgia, Wisconsin, and Nebraska’s Second Congressional District—would have given Donald Trump 270 electoral votes, enough for him to win a clear reelection.

This electoral factoid is worth remembering, because it helps us to appreciate the enormous political value of precise vote-targeting. Such targeting is indeed a part of political battlefield-shaping. If a campaign, or a political party, has the right plan, it’s often possible to eke out a victory, even if circumstances are otherwise unfavorable.

The key is information—and then knowing what to do with it. As they say, “knowledge is power.” And Sun Tzu would add, knowledge is victory.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.