Democrat presidential candidate Joe Biden’s “Build Back Better” agenda for combatting the coronavirus pandemic and its economic effects has its foundation in an international disaster relief program designed by the United Nations, a review of the origins of the framework and terminology reveal.

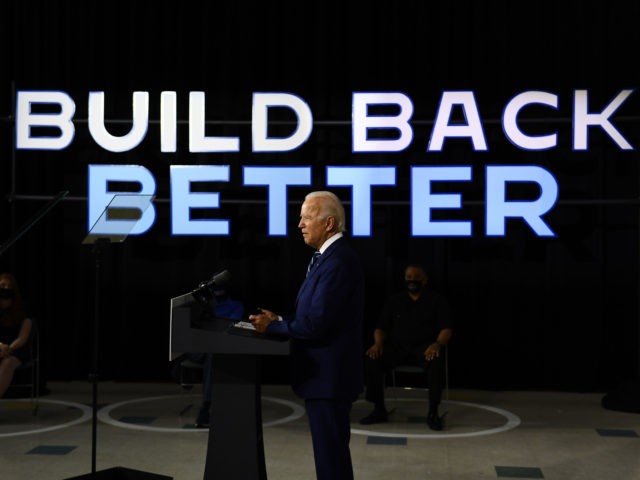

Biden’s “Build Back Better” plan, unveiled last month, has become a central part of his campaign. He and his newly announced running mate Sen. Kamala Harris (D-CA) tout it at every turn, and Democrats top to bottom sung its praises on the opening day of the Democratic National Convention this week.

While “Build Back Better” may sound like a catchphrase to heal the country, its history as a global framework used by international organizations and conglomerates for disaster relief building is more complicated. Nations, like Japan in the wake of its deadly 2011 earthquake, have used the framework and its central planning components to rise out of disaster. More recently, however, it has formed the centerpiece of progressive climate change programs, like the Paris Climate Accord — which Trump has exited and Biden promises to re-enter if elected.

By embracing “Build Back Better,” Biden and Democrats are laying out a vision for how to use the current crisis to not only reshape the United States in a progressive fashion, but also integrate it further into the global community.

“Tonight, I am asking you to believe in Joe and Kamala’s ability to lead this country out of these dark times and build it back better,” former President Barack Obama told the convention Wednesday.

The scale of that effort, as Obama described, remains to be seen, but prior frameworks based on “Build Back Better” may provide some clues.

As such, Breitbart News is providing an in-depth view into the proposal and its potential impact. Such analysis is needed since many editorials have provided fawning coverage of “Build Back Better,” while giving little effort to analyzing why the proposal, if implemented, would make Biden the most progressive commander-in-chief since President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction:

Biden’s “Build Back Better” agenda has its foundation in a set of principles first defined at the third United Nations World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction in Sendai, Japan in March 2015. During the conference, which was tasked with developing strategies for dealing with national disasters and minimizing their likelihood, a delegation from Japan proposed that any international framework on the topic include a holistic approach to post-disaster rebuilding.

The approach, called “Build Back Better,” the delegation told the conference was the key to Japan’s ability to bounce back after being struck by a magnitude 9 earthquake in March 2011, which also triggered a catastrophic tsunami and a major nuclear meltdown. According to the Japanese delegation, “Build Back Better” was a mechanism through which nations could see disasters as an opportunity to reconfigure their societies.

“Japan is working on the reconstruction … based on the idea of ‘Build Back Better,’ which aims not simply to recover the same situation that existed prior to the disaster, but rather build a society that is more resilient to disasters than before,” Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe told the conference.

Part of that new resilience would come not only by designing new infrastructure to reduce the risk of disasters, but also revitalizing economic livelihoods and protecting the environment. Japan’s delegation informed the conference that the concept behind “Build Back Better” was not new, having been used in one form or another since the late 1990s. Most notably, the concept was advanced to great success in the mid-2000s by former President Bill Clinton, then a U.N. special envoy for tsunami recovery, as a means for countries to rebuild post-natural disaster.

Given the history, Japan’s push to include the approach in the broader disaster risk reduction program proved widely popular. The final version of the Sendai disaster framework, including an entire section on how nations could “Build Back Better,” was approved by the U.N. General Assembly in June 2015.

“Build Back Better” in the Age of Climate Change:

Shortly after the framework’s passage, Sendai’s ambiguous text regarding what constitutes “Build Back Better” ensured the concept could be expanded to meet a bevy of political considerations.

This was first exhibited in April 2016 as the U.N. was preparing to sign the Paris Climate Accord. That month, the World Bank Group launched a major initiative to streamline building regulations for post-disaster rebuilding. In essence, the World Bank, in conjunction with the Global Facility for Disaster Risk Reduction, would undertake a lobbying campaign to convince countries vulnerable to disasters to adopt national legislation mandating that all new construction would energy-efficient and built to withstand natural hazards.

According to the U.N.’s Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, the new initiative would help go a long way to helping mitigate “unregulated urban development” across the globe. Much of the World Bank Group’s priorities for the initiative also overlapped with the goals and strategies outlined in the Paris agreement, ensuring a broader emphasis on the risks and consequences of climate change.

As nations across the world began taking the initial steps in implementing the Paris Accord in 2017, “Build Back Better” became even more openly wed to the efforts to combat climate change. In February of that year, the U.N. General Assembly adopted a resolution defining ways in which “global progress in reducing disasters losses” could be measured. The resolution heavily expanded the “terminology related to disaster risk reduction” to include the topic of climate change in order to guide “to guide policymakers and decision-makers” in crafting better plans to mitigate natural disasters.

“This is a major achievement … to reduce [the] loss of life and economic losses, in the face of deadly climate change, risk-laden investment in infrastructure, poorly planned expansion of cities and towns, poverty, and continuing environmental decline,” Robert Glasser, then-the U.N.’s special representative for disaster risk reduction, said at the time.

Following the resolution, climate change began popping up and more as the center-piece of international post-disaster planning.

Coronavirus and Biden:

Throughout most of the Democrat nominating contest, the former vice president campaigned as an unabashed moderate. Unlike more progressive rivals, including Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Bernie Sanders (I-VT), Biden refused to propose wide-sweeping measures on healthcare or the economy. Biden not only refused to utilize such tactics but openly castigated Sanders and Warren for pushing an unrealistic agenda.

Most notably, this was the case with Medicare for All, the signature healthcare policy of Sanders, and the Democrats’ progressive wing. Throughout the primaries, Biden assailed Medicare for All as politically untenable, even at times accusing proponents of lying about its true financial cost.

Biden’s stance against radical change, however, began to evolve in mid-March as the novel coronavirus pandemic ravaged the United States, causing a public health and economic crisis.

The evolution was most prominent in the former vice president’s rhetoric. Prior to the crisis, Biden focused much of his public comments on attacking President Donald Trump for his character, accusing the commander-in-chief on more than one occasion of denigrating the “soul of the nation.”

With the emergence of coronavirus, though, Biden began emphasizing a broader economic and social program to “transform” America. While the former vice president still lambasted Trump openly, now more of his public utterances centered on what would be required to rebuild the country after the pandemic. On more than on occasion, Biden has compared the challenge ahead to that faced by FDR at the height of the Great Depression.

“The blinders have been taken off,” Biden told donors at a virtual fundraiser earlier this year, “because of this COVID crisis, I think people are realizing, ‘My Lord, look at what is possible. Look at the institutional changes we can make.’”

Biden Embraces “Build Back Better”:

It is unclear when Biden first became aware of the concept of “Build Back Better,” at least as defined by the U.N., but its influence is exhibited throughout the former vice president’s plan for a post-coronavirus recovery.

For example, Biden’s proposal mirrors more than just the “Build Back Better,” name. It incorporates the concept’s main tenant that natural disasters can be a trigger for building more resilient and equitable societies.

“This is the moment to imagine and build a new American economy for our families and the next generation,” the former vice president’s plan reads.

As such, Biden’s plan includes an extensive framework for rebuilding America’s supply chain infrastructure, with a focus on vital medical equipment. The issue is particularly important since the coronavirus has exposed how dangerously dependent the U.S. has become on foreign suppliers, notably China, for personal protective equipment and medical supplies.

Although unrelated to COVID19, Biden’s proposal also prioritizes investments in clean energy infrastructure. The former vice president has urged updating four million buildings across the country to meet energy efficiency standards. His plan further provides federal funding for new weather-resistant infrastructure projects, like roads and bridges.

Such ideas are directly in line with the U.N.’s model for reducing disaster risks.

“Build Back Better” Meets New Deal:

Where Biden’s plan becomes more ambitious than the U.N. model is on the economic issues that have dominated domestic politics over the past four years.

“Biden believes this is no time to just build back to the way things were before, with the old economy’s structural weaknesses and inequalities still in place,” the former vice president’s plan states.

The strong emphasis on fixing “the old economy’s structural weaknesses” is where the New Deal’s influence on Biden’s thinking becomes clear. The former vice president is proposing not only to help the country recover from the COVID19 pandemic, but to use the power of the federal government to revamp the national economy while doing so.

For instance, Biden has unveiled a comprehensive “Buy American” proposal that his campaign claims will create five million domestic manufacturing jobs. The proposal is anchored around a $400 billion federal procurement program. It also includes a further $300 billion investment in U.S.-based research and development programs to ensure “the future is made in all of America.”

Similarly, the former vice president has proposed an ambitious and costly plan to protect the environment.

Biden’s plan, heavily influenced by the recommendations of a unity task force set up earlier this year by the presumptive nominee and his vanquished primary rival, Bernie Sanders, suggests spending $2 trillion over four years to combat climate change.

A major portion of the money will be used to create one million new jobs in the auto industry by boosting the production of energy-efficient vehicles. In order to achieve the goal, Biden is backing legislation, introduced by Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY), to incentivize individuals to trade in their gas-powered vehicles for ones running on either electricity or hydrogen.

Biden has also proposed to adopt a 100 percent clean-electricity standard by 2035. If implemented, this would likely have a massive impact on the coal and natural gas industry jobs. According to the Energy Information Association, coal and natural gas produce 63 percent of all the electricity consumed across the U.S. annually.

To help implement the wide-reaching agenda, Biden is proposing the creation of an environmental conservation corps, based on a popular poverty-relief program from the New Deal. The corps will pay individuals to work on green energy infrastructure projects, such as plugging abandoned mines and wells.

More than a Passing Link:

The extent to which Biden’s campaign based its response to the novel coronavirus on the U.N.’s framework for “Build Back Better” and prior New Deal efforts is uncertain. The former vice president’s campaign did not respond to requests for this story.

The recent timing of events, though, seems to indicate more than just a passing link between. As mentioned, Biden has frequently begun invoking FDR on the campaign trail, comparing his own efforts to navigate a post-coronavirus world to the former president’s decision to launch the New Deal. Likewise, there are strong indications Biden’s “Build Back Better” agenda shares more than a name with its U.N. counterpart.

In June, a month prior to Biden’s proposal being made public, the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OCED) released an in-depth study on how nations could use “Build Back Better” to achieve “a sustainable, resilient recovery after COVID-19.”

OCED, which holds official observer status with the U.N., explored various options for achieving the goal. Included among its suggestions were creating “public procurement processes,” improving the “resilience of supply chains,” and investing in long-term green energy projects. The study’s central takeaway was that any coronavirus recovery effort that does not improve “inclusiveness and reduces inequality” could not succeed.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.