The new push by Michigan Democrats to institute the option of vote-by-mail ahead of November may end up ensuring the state, which was already going to be close, does not report its results until well after Election Day.

On Tuesday, Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson announced that every single voter in the state will receive an application to vote by absentee ahead of the upcoming local and federal elections. Benson, who prior to being elected Michigan’s chief elections officer in 2018 was a noted opponent of voter ID laws, claimed the decision was made in order to mitigate the public health concerns arising from the coronavirus pandemic.

“By mailing applications, we have ensured that no Michigander has to choose between their health and their right to vote,” the secretary of state said in a statement, adding that “voting by mail is easy, convenient, safe, and secure, and every voter in Michigan has the right to do it.”

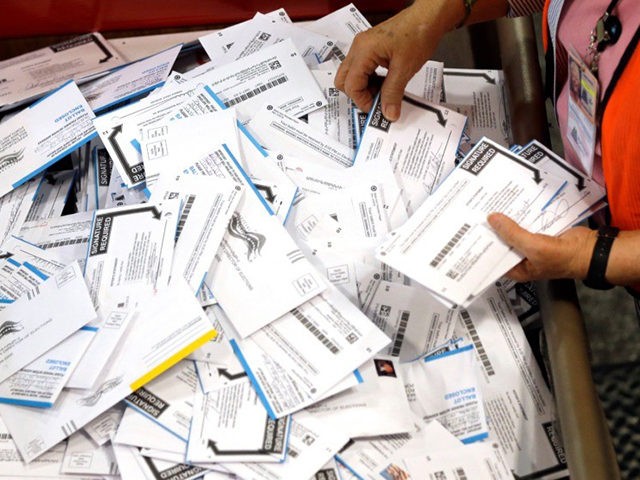

Under the new policy, Michigan’s Bureau of Elections will send every registered voter a letter informing them of the procedure required to receive an absentee ballot to vote by mail in the fall election. To receive their absentee ballot, voters will only have to respond with their signature either on the application or by emailing a photo of it to a local department of elections.

The policy, though, is fraught with potential risk. Absentee applications are to be mailed to the last address on file, which could mean that voters who have moved and not updated their information with the bureau of elections may miss out.

Registered voters without fixed addresses or those with unreliable mail service are also at a disadvantage under Benson’s policy. Although such voters would be eligible to cast ballots in person on election day, there is no indication the state would have the resources to keep polling properly staffed or open if the coronavirus were to return in the fall, as Michigan Democrats speculate.

Similarly, vote-by-mail is problematic for individuals with disabilities or those without a proper grasp of the English language. Such voters generally rely on in-person assistance at polling locations to exercise their constitutional rights.

Some also argue that widespread vote-by-mail will be a logistical nightmare for Michigan’s state and local election bureaus. Not only would such bureaus need to have the appropriate equipment, such as specialized high-speed scanners, to process large numbers of absentee ballots, but they would further have to mount public awareness campaigns informing voters on how to vote by mail.

Such efforts would likely prove a burden on local governments, which are already facing difficulty because of the coronavirus, and could delay the reporting of results well after Election Day, creating political instability. Wisconsin recently indicated the possibility of this scenario when it took more than a month to count at least 30,000 outstanding mail-in ballots from the state’s April 3 Democrat presidential primary. Meanwhile, less than 100 of the more than 400,000 voters who showed up to the polls in Wisconsin for that primary were later confirmed to have contracted the coronavirus. Roughly, that equals an infection rate below two-hundredths of one percent.

Benson’s decision also bypasses a law enacted by the Michigan legislature two years ago allowing anyone to vote by absentee ballot for any reason, provided they make adequate preparation ahead of time to receive such a ballot.

Since that law was enacted approximately 1.3 million voters, out of the state’s total 7.7 million registered voter population, have qualified to vote absentee. The practice was widespread during Michigan’s recent Democrat presidential primary in March, where 38 percent of those who voted did so by an absentee ballot due to the coronavirus outbreak.

As the existing law has not shown any problems, even in the face of a public health crisis such as COVID-19, many believe that Benson’s action will be challenged in court by Republicans and voter-integrity groups.

If the secretary were to succeed, however, vote-by-mail could end up making Michigan even more of a toss-up at the presidential level. Michigan, like much of the Midwest, was once solidly in the Democrat camp until 2016, when then-candidate Donald Trump broke the status quo by becoming the first Republican to carry the state since 1988.

Trump’s victory, although by a narrow 11,000-vote margin, was made possible by the large-scale defection of white working-class voters, who generally supported Democrats but were drawn to the president’s populist stances on immigration and trade.

Since then the state has become more politically volatile, shifting to Democrats at the state and federal level during the 2018 elections. In 2020, with polls showing former Vice President Joe Biden competitive in the state and across the Midwest as a whole, Michigan tops the list of must-wins for both Democrats and Republicans.

Given that political reality, Republicans have expressed concerns about Benson’s proposal moving forward. Many, in particular, have raised the specter of voter fraud, especially as even a few thousand votes could shift the contests, and Michigan’s correspondent electoral college votes, to either presidential candidate. Of notable concern is ballot harvesting, which allows third-party individuals to collect and drop off absentee ballots en masse.

The practice, which has been banned in some states, was on display in the close election for North Carolina’s Ninth Congressional District in 2018. An operative hired by the campaign of the then-Republican nominee was later charged with voter fraud after it emerged he and people in his employee had illegally collected absentee ballots from rural counties throughout the district. A number of the ballots, mainly those belonging to older black voters, were delivered to the local board of elections at rates significantly lower than those of older white voters.

The GOP operative succeeded in collecting and delivering ballots even as North Carolina had laws prohibiting such conduct for some time. That illegal harvesting resulted in the congressional race being invalidated since neither of the candidates had a clear majority and the absentee ballots would have been required to determine a victor. A special, redo election had to be held for the seat, nearly a year after the initial voting took place.

Although Michigan law bans voters from possessing another individual’s absentee ballot or absentee application form, the law does allow family members of the voter or registered electors. The law also bans third-party individuals from delivering absentee ballots to election bureaus unless they are asked to provide such assistance ahead of time. Some, though, believe that does not go far enough, as witnessed by the events in North Carolina.

President Donald Trump, himself, weighed in on the issue of vote-by-mail in Michigan on Wednesday, asserting that he would withhold federal funding from the state if it opted to go down the “voter fraud path.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.