The Supreme Court properly ruled on Friday in favor of the Trump Administration and against the Sierra Club, which improperly sued the government in an attempt to exploit our legal system and interfere with the will of the American people.

This is a giant victory for conservatives and for the administration that was made possible by a simple campaign pledge: to appoint judicial nominees off a list given to the people in advance of the general election.

Now, going into 2020, candidates challenging Donald Trump should make the same move – publish their list of potential judicial nominees for the highest court.

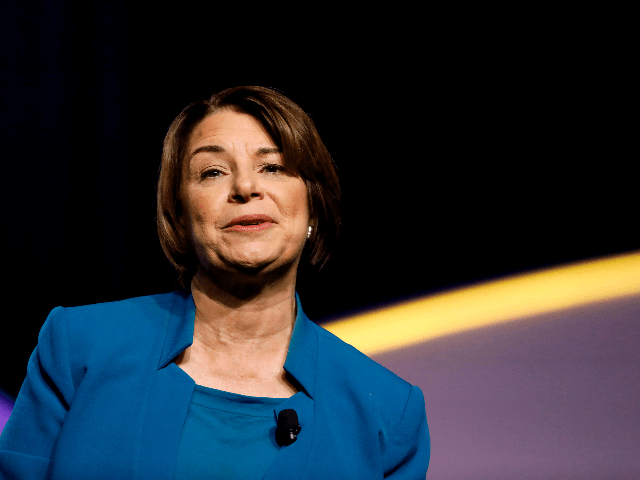

The good news is, Sen. Amy Klobuchar is the first Democrat to say she’ll be ready to nominate a full slate of qualified judges on her first day in office, and that puts her in the news. The bad news is, she says she won’t make her list of potential judges public until after she wins the presidency.

Appearing two Mondays ago on a National Public Radio podcast, Klobuchar said she “wouldn’t consider releasing the names of potential judicial nominees unless and until she manages to emerge from the crowded primary field victorious and then ousts Trump in the general election,” according to Susan Crabtree at Real Clear Politics.

“I think that you interview people, you make decisions – and you can’t do that as a candidate,” said Klobuchar. “You can’t vet them like you should. As a candidate, you don’t have the FBI.” She’s right. As a candidate, you do not have the FBI to vet your candidates for judicial openings.

Of course, that didn’t stop then-candidate Donald Trump from constructing and then releasing a list of potential judicial nominees during his successful 2016 campaign for the GOP nomination and the presidency.

As Mollie Hemingway and Carrie Severino discuss at length in the second chapter of their new book, Justice on Trial: The Kavanaugh Confirmation and the Future of the Supreme Court, the Trump list proved crucial not just to Trump’s success in winning over skeptical GOP primary voters, but to Trump’s eventual success in the general election, as well.

Trump’s list was actually two lists before the election. The first contained eleven names and was released on May 18, 2016, after Trump had won the crucial Indiana primary to effectively secure the GOP nomination. The second list, with an additional ten names, was released on September 23, 2016, three days before the first general election debate.

No candidate for president had ever before released such a list of potential judicial nominees during a campaign. In fact, most had gone to great lengths to maintain radio silence on the names of potential nominees, obfuscating the issue when asked by confining themselves to speaking in vague generalities about the “qualities” and “character” they would like to see in their nominees. When Trump rejected the conventional wisdom, it spoke volumes.

“The publication of a list of hard-core conservatives in the middle of a general election campaign spoke to how different Trump was from a traditional Republican,” Hemingway and Severino write. “Most GOP candidates run to the right during the primaries, only to tack to the center during the general election campaign. Trump’s approach was to stay right where he was but force his opponent farther to the left.”

History shows it worked. Exit polls revealed two eyebrow-raising statistics: First, 21 percent of voters said Supreme Court appointments were “the most important factor” in deciding their votes. And that one-fifth of the electorate broke hard for Trump over Clinton, 56-41 percent.

Second: More than a quarter of Trump’s voters – 26 percent, in fact – told pollsters that “Supreme Court nominees were the most important factor in their voting, compared with only 18 percent of Hillary Clinton voters who said the same.”

Trump knew just how important the list was to his electoral success. Writing of Trump’s first post-election meeting to discuss filling the Supreme Court vacancy, Hemingway and Severino reveal:

Trump began the meeting by discussing how consequential the Supreme Court issue was for voters. He knew the polling data, which showed that 26 percent of Trump voters said the Supreme Court was the basis of their decision. Trump joked that Clarence Thomas’s name received more applause at rallies than his own.

Trump’s successful creation and publication of the list changed the way campaigns for president will be run in the future. From now on, all serious candidates for president should be required to construct and publicize such lists, even if they think it would be politically damaging. Even some Democrats seem to get this. Brian Fallon, executive director of Demand Justice, a progressive advocacy group, said:

The Democratic nominee for president should release a list of potential nominees. Not just because it is good politics in the sense that it would rally a progressive base behind a more concrete possibility about whom we might get on the Supreme Court if we vote for that person. It’s also the right thing to do from the standpoint of explaining what your priorities are.

Fallon is right – Klobuchar and her fellow candidates should release their lists so that we can all take a look and make our own judgments. In today’s political climate of media fueled culture wars, where various non-profit groups sue the government over policy disagreements, it’s becoming more apparent to the American public that promises by a politician cannot be backed up without court appointments. For any voter to make an educated choice on a Presidential candidate, he or she needs to know whom the candidate will appoint to the federal bench. But also, it’s the right thing to do. Otherwise, we’ll just be left chasing Amy.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.