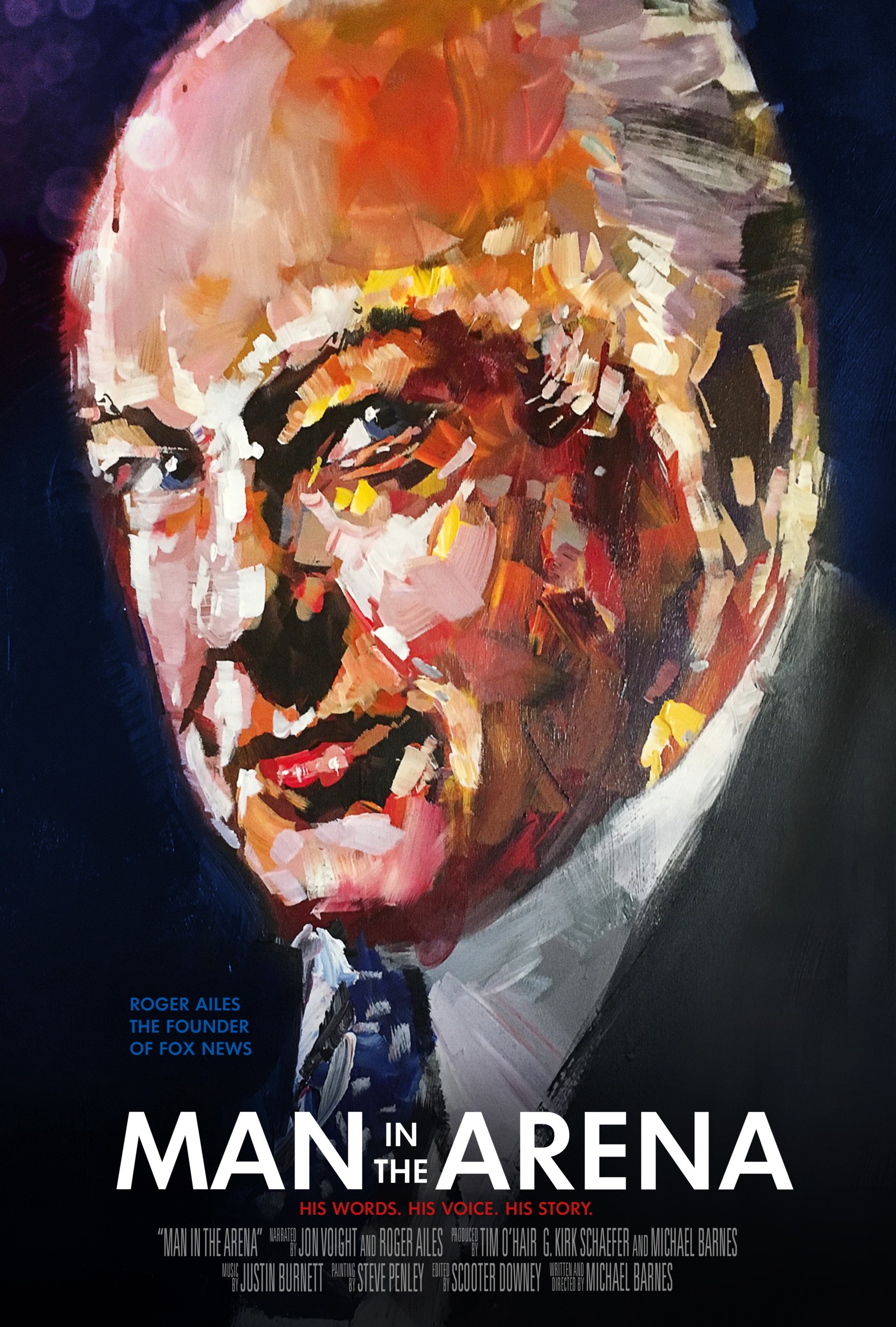

Who better to tell the story of Roger Ailes than the man himself? Isn’t it about time that the legendary political and media warrior—the object of so much hostile fire over the course of five decades—has the opportunity to respond, speaking in his own voice? Now, in a new documentary on his life, work, and struggles, Man In The Arena, available on Amazon, Ailes gets his chance.

Of course, Ailes died in 2017, a year after he was forced out of Fox News, the network he launched and then built into a mighty juggernaut. And yet Ailes speaks again today, thanks to the efforts of documentary director, writer, and producer Michael Barnes, a Los Angeles lawyer-turned-auteur, who had access to hundreds of hours of autobiographical audio tapes that Ailes had recorded in the years prior to his death.

Moreover, Barnes interviewed a galaxy of luminaries who knew Ailes well, including Donald Trump, Rush Limbaugh, Newt Gingrich, Dan Quayle, Mitch McConnell, Lara Logan, Rudy Giuliani, and Bill O’Reilly. And oh yes, Academy Award-winning actor Jon Voight provides additional narration. (This author had a hand in the documentary’s production, too, having worked with Ailes for most of the years 1986 to 2016.)

In addition, the documentary features interviews with Ailes’ widow, Liz; his son, Zachary; and his brother, Rob. Thanks to them, Barnes gained access to a museum-worthy trove of photographs, documents, and memorabilia, illustrating Ailes’ life and times, as he moved through top roles in three victorious presidential campaigns (Richard Nixon’s in 1968, Ronald Reagan’s in 1984, and George H.W. Bush’s in 1988), as well as dozens of other campaigns, followed by leadership roles at CNBC and Fox.

The result is a fine-grained documentary portrait of a man of great accomplishments, and yet also, as the film makes clear, of tragic flaws.

Born in 1940 to a blue-collar family in the gritty industrial town of Warren, OH, Ailes’ original ambition was to be a fighter pilot, despite suffering from the crippling and life-threatening disease of hemophilia. That blood malady was so severe that he spent weeks at a time in hospitals—although, even from a sick bed, he dreamed of a bigger world and wider opportunities. As an older Ailes recalls of his younger self, “I always believed myself to be a lion. That I would do something important one day.”

Indeed, through persistence and a bit of trickery—he personally erased the disqualifying “hemophilia” diagnosis in his own medical file—he got himself into Air Force ROTC. Yet a few years later, his medical condition was uncovered, and he was washed out of a career in the armed services.

Seeking a new horizon, Ailes talked his way into television, starting as a prop boy and rising to be executive producer of The Mike Douglas Show at age 25. And it was under Ailes’ guidance that Mike Douglas soon became the number-one syndicated daytime host in America, welcoming guests ranging from Bob Hope to the Rolling Stones to Ann-Margret to Martin Luther King, Jr.

In fact, Ailes’ 1967 encounter with yet another guest on the show, Richard Nixon, led to a job offer to join Nixon’s presidential campaign. And here, as Ailes relates in his own voice, we see the skill of a TV master, plotting out Nixon’s media strategy, as he fitted the candidate’s persona into a plan for victory.

As we know, the easy thing to say about televised politics is that it’s all about flash and dash—and yet Nixon was anything but flashy and dashing, and Ailes knew that in the end, the camera doesn’t lie. So no matter what was tried, Nixon was never going to be a leading-man type. Yet at the same time, Nixon had strengths: He was smart and lawyerly, possessed of vast experience in high office, including eight years as Dwight Eisenhower’s vice president.

So the winning media strategy was not to present Nixon as somebody he wasn’t, but rather, as somebody he was. That is, highlight the man’s demonstrable strengths. Nixon might never have been handsome or charismatic, but he was always intelligent, lawyerly, and quick on his feet—and maybe that was enough.

Thus Ailes’ challenge: To be creative in presenting Nixon as the best he could be: a man smart enough, and tough enough, to be president. As Ailes recalls, “I was trying to come up with a new way to do new things.”

Here, Ailes’ lifelong interest in history came to his aid: “I was researching Nixon, and I saw that he liked Teddy Roosevelt, and I began read Roosevelt, and I found, ‘In the Arena.’ It sounded like Nixon.” TR’s “In the Arena” speech, from 1910, includes this famous passage:

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause.

Thus the commonality emerged in Ailes’ mind: TR as a tough fighter, and Nixon as a tough fighter, too. So now, how to get Nixon into the arena? Here’s Ailes: “I realized that if I could build this out of something that he believed . . . If I could get a person organically closer to the material because he actually believed the material, and believed in the setting, it’s not a phony staging.”

Then Ailes added a topper to his production plan: Do it live. Speaking of his fellow Nixon campaign staffers, Ailes continues, “They all said, ‘That’s too dangerous.’” To which Ailes responded, “This guy, under fire, he was a pretty cool customer, him against the world.”

Indeed, he said to Nixon himself, “Your whole life has been you against the world, and this will be the challenge of your life.” Nixon agreed, and ten one-hour shows, called, fittingly, “Man in the Arena,” aired during the 1968 presidential campaign. Nixon won.

The following year, 1969, Ailes had the responsibility of televising President Nixon from the Oval Office during a live simulcast with the Apollo 11 landing on the moon. Such simultaneous juxtaposition is a lot easier to manage now than it was then—and yet both the moon landing, and the White House televising, went off flawlessly. Ailes was not yet 30 years old.

Shortly thereafter, Ailes had a falling out with the Nixon people, which was perhaps just as well, since they were soon consumed by the Watergate scandal. In the meantime, Ailes had moved to New York City, where he was soon producing shows, on and off Broadway, winning an Obie award for the hit play Hot l Baltimore.

In addition, Ailes’ TV-documentary work led him into close contact with everyone from political scion Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. to mass-murderer Charles Manson. (We see at least glimpses of all of this in Man in the Arena.)

Yet Ailes’ heart was always with conservatism and the Republican Party. He was, in fact, an ardent patriot, forever in love with the country that given him a shot at the American Dream.

So in the 1970s, Ailes moved into political consulting, providing the media vision for Republican candidates from Connecticut to California. (One of those candidates he helped was a local official in Kentucky, running an underdog campaign against an incumbent U.S. Senator. Ailes whipped up an hilariously funny—and devastatingly effective—spot, and Mitch McConnell came from behind to win the race. Four decades later, the senate majority leader repays the favor, describing Ailes as one of the three most influential conservatives of the modern era.

That same year, Ailes gave President Ronald Reagan the sound bite that clinched his victory over Walter Mondale in a presidential debate: “I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience.” Even Mondale himself laughed at that one, and Reagan won in a landslide.

In 1993, Ailes took over as head of CNBC. He jazzed up the the channel’s daytime business coverage even as he maintained it—in those pre-Internet days, most stock traders relied on TV for news—and yet for the evening, he created a new category of prime-time showmanship, hosted by those he dubbed “The All-Stars of Talk.”

Among the talkers Ailes cultivated were up-and-coming stars Chris Matthews, Geraldo Rivera, and Jim Cramer. Indeed, while at CNBC, working with his soon-to-be-wife, Liz, he created a new cable channel, America’s Talking, in which he himself had a show, interviewing everyone from Camille Paglia to James Earl Jones to Boy George. Yet Ailes’ ultimate goal was to create a more conservative channel, a kind of proto-Fox News. However, when NBC management balked, Ailes walked.

Then, in 1996, Ailes joined with Rupert Murdoch to launch Fox News; it was soon, just as Ailes had pledged, “The Most Powerful Name in News.”

During his time at Fox, Ailes himself was the most powerful man in television. He had gotten to the top through hard work, creativity, and determination, even as the hemophilia—as well as other health problems, such as prostate cancer—increasingly crippled him.

Indeed, given his physically weakened condition—which prevented him from being a physical threat to anyone—what happened next was ironic, as well as tragic. Interestingly, Ailes had always had premonitions about his own doom; in the film, we see him say to an audience, “Each of you has a personal ego pit out there in the dark, waiting for you, some place, sometime, if you fall in, the sides are steep, they are slippery, and you may never get out.”

At this point, Man in the Arena pulsates with dramatic intensity. Like a tragic figure from Sophocles or Shakespeare, Ailes might have been on top, but jealous and conniving figures around him were plotting to strike him down.

Best-selling author Michael Wolff suggests that one of the plotters was Rupert Murdoch himself. Yes, Murdoch had hired Ailes and had garnered billions from Ailes’ work at Fox, and yet at the same time, he had grown envious, realizing that Ailes was getting more attention than he. Moreover, Murdoch was determined that the succession of the company would come to his own under-achieving sons. In Wolff’s words, the events that were soon to engulf Ailes were “part of a concerted, long term, and, I might say, masterful plan on Murdoch’s part.” That is, a plan to be rid of Ailes.

To be sure, many will say that Ailes contributed to his own downfall. In the decade of the 10s, after all, he still sometimes talked like a man from the Mad Men ’60s. As a longtime colleague, Larry McCarthy, recalls, “Not everybody liked Roger’s style, which was funny, profane, conversational, blunt.” Indeed, anyone who was around Ailes knew that he was funny, profane, conversational, and blunt—oftentimes all in the same sentence. It was a mark of Ailes’ candor that he simply said whatever was growing in his fertile brain.

Yet still, Ailes had run Fox for nearly two decades without any sort of awkward or untoward incident. In fact, the film features an interview with former Fox host Kiran Chetry, who recalls that she was in his office some two dozen times over the course of her stint at the channel, and yet “he never hit on me, never made me feel uncomfortable.”

And yet other women obviously felt differently. In July 2016, another Fox host, Gretchen Carlson, recently let go by Ailes, accused him of sexual harassment. Carlson’s accusation was damaging, and yet when it was followed up by another accusation, this one from one of the brightest stars on the channel, Megyn Kelly, Ailes’ fate was sealed; he resigned that same month.

So what actually happened? Here, Man in the Arena makes some interesting choices: As for Carlson, we see Ailes emphatically denying the accusations, and yet the film notes that legal agreements prohibit any further discussion of the case.

As for Kelly, she’s a different story; she is depicted as both a climber and an ungrateful backstabber. As the film recalls, in 2015, when Kelly found herself in an unpleasant rumble with Donald Trump, Ailes strongly defended Kelly. In fact, in a TV interview back then, we see Kelly saying of Ailes, “He’s been nothing but good to me. He’s been very loyal. He had my back.”

Then, in 2016, everything changed. How, exactly? Well, there’s no point in giving away one the film’s juiciest secrets; for the moment, let’s just give the last word to Rush Limbaugh who sagely observes, “In the media world . . . the central dominating factor is the ego. I think it’s at that point that all considerations of loyalty, and gratitude vanish and end up being replaced by anger and the need for revenge.”’

Interestingly, there was a third major sexual allegation concerning Ailes—and this one, the film actually confirms, through the searing and heart-rending recollections of Mrs. Ailes herself. And therein we see a profoundly tender moment of humanity; with tears in her eyes, Liz Ailes recounts her husband’s contrition, and redemption. As a result, she adds, “I kept my marriage together. I believe in forgiveness . . . I think the world has forgotten how to be compassionate.”

Tantalizingly, even as he was near death, Ailes planned still another big project. Recalls his widow, who had been his behind-the-scenes TV partner for decades: “He toyed with the idea of doing something to compete with Fox News. He had that street-fighter mentality, he was not one to give up, so he was going to come back.” And then, of course, he died.

Yet in Roger Ailes’ own voice, we hear, “It’s the uncompleted mission of my life.”

Three years after his passing, we may never know what that uncompleted mission was meant to be. Or, perhaps, we will find out.

After all, there’s one thing for sure about a warrior’s spirit—it never dies. Yes, the warrior’s body may wither, but the fighting spirit never fades. There’s always some younger warrior who will enter the arena, pick up the sword—and start fighting.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.