Chuck Bednarik fought Nazis in the skies over Germany. Then he drove Frank Gifford into the earth in the Bronx.

The last of the NFL’s 60-minute men passed away Saturday morning at 89. He leaves behind one of the most iconic images in NFL history and takes from us the last link to old-school football.

Six years before the Philadelphia Eagles drafted him with the first pick in 1949’s NFL Draft, Bednarik beat Uncle Sam’s draft by signing up for the Army. During World War II, a third of the league deserted the football field for the battlefield—forcing the Cleveland Rams to fold for the 1943 season and the amalgamation of the Steelers and Eagles that same year. Such future players (and Hall of Famers) as Bednarik, Art Donovan, and Tom Landry joined the fight, too. Bednarik served as a tailgunner on 30 missions in a B-24 in the European theater.

“My last mission was on April 23, 1945, over a city called Swiesel,” Bednarik told biographer Jack McCallum. “That was the last for me, the 30th, which is the number required. When we got back to England, I got out and kissed the plane, kissed the ground and announced that I was never going to fly again. Never. Of course, as it turned out, all I did was fly as a football player and now in my travels.”

He entered the Army in 1943 a 180-pound 18-year-old. He emerged from it a grown, grizzled man. He subsequently won repeat All-American honors at Penn. His selection by the Eagles, and 14 seasons in Philadelphia, ensured that Bednarik would play the entirety of his gridiron career—starting in Bethlehem’s sandlots with a football made by his mom, who stuffed a stocking with rags—for Pennsylvania teams.

Everything about Chuck Bednarik screamed “throwback.” His face, physiognomy—even the man’s name—evoked football in the trenches. One might say Chuck Bednarik appears about as 2015 as drinking a Ballantine on a tenement house fire escape to the musical accompaniment of a Perry Como .78. But this falls short. Bednarik strode the field as an atavism even to his contemporaries.

The son of a Slovak immigrant Bethlehem Steel worker started his NFL career without a facemask and ended it with a face that resembled a topographical map of Pennsylvania. In between, he acted as a human remnant of one-platoon football by playing linebacker and center. After missing two games his rookie season, he sat just once during his remaining 13 years in the league. He grinded out every game but three even though he played on both side of the ball some seasons, and contributed on special teams as well. He boasted a punting average of over 40 yards for his twelve kicks in 1953 and even booted the ball during 1954’s Pro Bowl, a game he made eight times during his career, initially as a linebacker and later as a center. At halftime, when Bednarik took a break from tackling, snapping, and punting, he smoked several cigarettes.

“I guess our bodies were in such good shape that the smoking itself didn’t bother us,” the 235-pound bruiser noted of his pack-a-game-day habit in Bednarik: The Last of the Sixty Minute Men. “I’ve since given it up.”

In addition to smoking during halftime, Bednarik naturally drank straight whiskey to rejuvenate his depleted, 35-year-old body after playing sixty minutes in the 1960 NFL championship game that ended favorably for Philadelphia with #60 tackling, and holding down, Packer Jimmy Taylor as the 4th quarter ticked away. Mr. Eagle copped to popping Benzedrine pills for night games and putting a bounty on a player he disliked. Bert Bell’s NFL was not Roger Goodell’s.

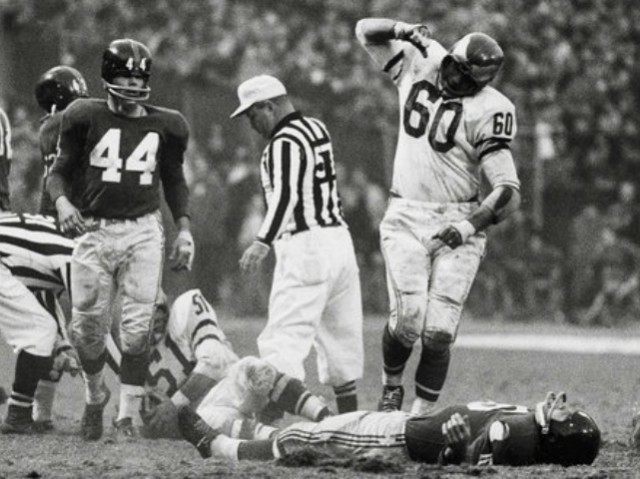

Though a Maxwell Award-winner as a Quaker and member of the Eagles’ last championship team, Bednarik’s lore looms largest because of a single play in a sold-out Yankee Stadium during that 1960 championship season that sent Frank Gifford out of football through the following year.

A John Zimmerman picture told a thousand words. A few years later, Frederick Exley added a few of his own in A Fan’s Notes:

I watched Bednarik all the way, thinking that at any second Gifford would turn back and see him, whispering, “Watch it, Frank. Watch it, Frank.” Then, quite suddenly, I knew it was going to happen; and accepting, with the fatalistic horror of a man anchored by fear to a curb and watching a tractor trailer bear down on a blind man, I stood breathlessly and waited. Gifford never saw him, and Bednarik did his job well. Dropping his shoulder ever so slightly, so that it would meet Gifford in the region of the neck and chest, he ran into him without breaking his furious stride, thwaaahhhp, taking Gifford’s legs out from under him, sending the ball careening wildly into the air, and bringing him to the soft green turf with a sickening thud. In a way it was beautiful to behold. For what seemed an eternity both Gifford and the ball had seemed to float, weightless, above the field, as if they were performing for the crowd on the trampoline. About five minutes later, after unsuccessfully trying to revive him, they lifted him onto a stretcher, looking, from where we sat high up in the mezzanine, like a small, broken, blue-and-silver mannikin, and carried him out of the stadium.

The violence of the hit, the lifelessness of its victim, and the death of a policeman at the stadium that day from a heart attack combined to mislead many Giants fans, already dejected by the visitors’ second-half comeback, into believing that Chuck Bednarik had killed Frank Gifford and then danced a jig over his corpse. The linebacker later sent a fruit basket to Gifford as the star of the screen and gridiron—different in almost every conceivable way from Bednarik save for his versatility on both sides of the ball—convalesced for more than two weeks in the hospital due to the Don Burroughs (low)/Chuck Bednarik (high) wallop.

Bednarik, forced to work in the offseason peddling cement because football never paid him more than $22,000 a year, sold the Eagles materials that helped build The Vet. Despite the commission, Concrete Charlie forged a rocky relationship with the organization in retirement. He remained in self-imposed exile for the better part of the 1970s after owner Leonard Tose overlooked him for several jobs, telling the retired 14-year player: “The Eagles don’t owe you a thing.” Head coach Dick Vermeil brought Bednarik back into the fold in 1976. But the opinionated athlete, whose mouth operated as bluntly as his body, endured several more spats with the team. After Eagles owner Jeffrey Lurie refused to purchase 100 copies of Bednarik’s book for $15 a pop in the 1990s, Bednarik openly rooted the following decade for the New England Patriots in Super Bowl 38 against the only professional franchise he had ever played for. Though Lurie’s team tweeted out “Forever an Eagle” to remember Bednarik on Saturday, the best player, arguably, in team history didn’t believe the organization lived by such a sentiment.

Concluding a week in which a 24-year-old rookie linebacker retired due to health concerns related to the game, the 89-year-old Bednarik’s death presents a different lens through which to view football. Tailgunner Chuck, whose B-24 took incoming rounds on each of his 30 flights, saw football as a fun respite from a hard world rather than a dangerous corner of a soft, safe space.

“You know what I wish?” Bednarik reflected after his career. “That God made us so we could play until we were 65. That would’ve been just long enough.”

Daniel J. Flynn, the author of The War on Football: Saving America’s Game, edits Breitbart Sports.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.