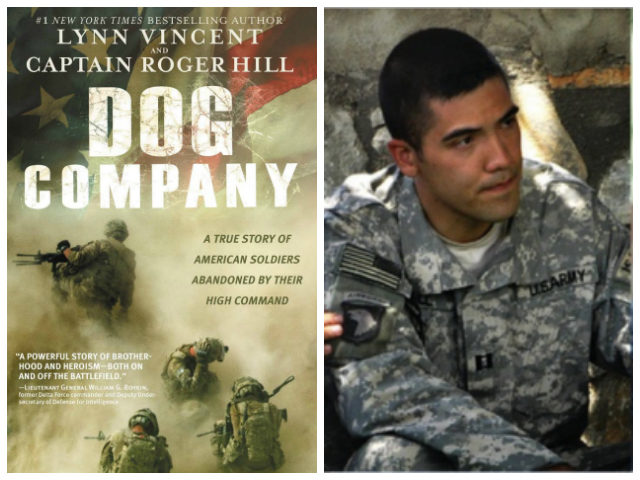

Army Captain Roger Hill joined SiriusXM host Alex Marlow on Wednesday’s Breitbart News Daily to talk about his new book, Dog Company: A True Story of American Soldiers Abandoned by Their High Command.

“The bottom line here is that we’ve got a set of politically driven rules of engagement that are getting our guys and girls overseas killed and hurt unnecessarily,” Hill said of his book’s urgent message.

LISTEN:

“This book Dog Company highlights a number of examples of that, in a real setting, during a real deployment to a province in eastern Afghanistan” in 2008 and 2009, according to Hill.

“My First Sergeant, Tommy Scott, and myself, we led a heavy weapons company in a violent province in eastern Afghanistan,” he recalled. “It seemed like the enemy was always one step ahead of us, and we discovered why. Through the aid of a counter-intel team, we uncovered twelve spies operating on our base. These were Afghan laborers that were hired by the U.S. government to serve as translators and other workers to support us so that we could focus on combat operations.”

“Also at that time, I was receiving credible intelligence that the enemy was planning a large-scale attack against my base. My command made multiple calls to our higher command to get these twelve spies taken off our hands, as was according to protocol. They would not,” he continued.

“Working against that clock, this credible intelligence of a large-scale attack, we decided to interrogate these spies ourselves to disrupt the attack. The interrogation consisted of me firing a weapon into the ground and scaring some detainees into talking. That led to an investigation, the investigation to a hearing, and a handful of us being drummed out of the military,” Hill said.

Marlow asked why the book is presented as “something the Army doesn’t want you to read.”

“There’s a thing that a lot of troops overseas refer to in a negative way, and it’s this ideal of ‘catch and release’ or ‘revolving door’ regarding our detainee policies overseas,” Hill explained. “A lot of Marines, a lot of guys from the Army on the ground have dealt with this, where you catch detainees, enemy combatants on the battlefield – in this case also spies – and our higher commands are forcing us to simply release them.”

“I’ve got a really vivid, colorful example of this among several throughout the book, but one that I’ll highlight right here is, we were in a firefight once in a very dangerous valley called Tangi Valley in Wardak Province,” he recalled. We pushed through the ambush line, came across some enemy fighters. We killed some, captured one guy. It just so happened that we blew his arm off. We’re a heavy weapons company, so Mark Nineteens, fifty-cal machine guns.”

“We patch him up, put a tourniquet on him, take him to Higher,” Hill continued. “They save his life, essentially, and they send him back to us two weeks later, and they say, ‘Hey, we know you caught this enemy fighter, but he’s outside that window of time you had to bring charges against him, so we need you to take him back to the point of capture – which is a very dangerous area – and release him.’”

He later noted that under NATO rules of engagement, troops in the field have only 96 hours to file charges against suspected enemy combatants or saboteurs, a time frame he called “insane” – especially since the enemy is well aware of the rules and knows how to run out the clock.

“I’ve been forced to give guys cab fare so they could go back to their villages after we captured them in combat operations,” he revealed.

Hill found it “disheartening” to be at odds with his government. “I feel like myself, my men have been discarded,” he said.

“However, when you take on a story like this – and this book has taken about seven years to write, the government has done a number of things to throw obstacles in our way, to prevent us from getting to publication, so it’s been a long journey. What happens when you write a story like this is, a lot of people start to come out of the woodwork and disclose their own experiences. So I know this is a pretty rampant problem, and I know the right thing to do is make light of it, so the American people know about what’s going on, and they can put pressure on our political system to make change,” he said.

“Our young Marines and soldiers do not get to pick and choose where they go to fight, what enemy they get to fight. That’s something we do, and by extension of our votes through the political process, our government does,” he noted.

“We have an obligation as a people, as a government, that when we send them into these complex environments – especially like the ones we’re dealing with in the Middle East, where the enemy fights and then basically falls back into their own populace knowing that they’re going to take civilian casualties, goading us into this sort of collateral damage – we have an obligation to stand behind our men and women in uniform when things go sideways, maybe when civilians are killed, and back them. We’re not doing that right now,” he urged.

Hill said his book is filled with instances of U.S. troops under fire “haggling with their high command” to justify requests for fire support or close-air support, illustrating that issues at the political, strategic, and tactical levels need to be addressed.

“The bottom line is, our rules of engagement need to be reviewed. Those parts of it that are overly restrictive and overly cumbersome need to be rolled back – especially now, before we consider stepping foot into another theater of conflict,” said Hill.

He described tactical command failures, such as failing to send a couple of Blackhawk helicopters to pick up the spies his unit discovered in Afghanistan, as “abandonment” of our troops.

“However, when they found out we interrogated these spies ourselves, they initiated an investigation, and they sent slews of Blackhawk helicopters into our base to bring in investigators to investigate us for our actions,” he added.

Hill looked back to 2003, when General Eric Shinseki told the Bush administration that at least 250,000 “boots on the ground” would be needed to win on the ground in Iraq, because “it’s not going in to invade a country that you have to worry about; it’s the phase three and phase four of rebuilding that you have to worry about.”

“We have only dealt with Iraq and Afghanistan in terms of tens of thousands,” he pointed out. “We have not even come close to the resources that are necessary to fight and win in that conflict, both in Iraq and Afghanistan. So we have constantly and consistently, from the very beginning, set our people up for failure.”

He further quoted World War II General Douglas MacArthur’s advice that the troops who defeat a wartime enemy should not also be tasked with rebuilding efforts, but “we’ve asked our people for the last 10 or 15 years to do both jobs, in an extremely under-resourced state.”

“All these things matter. All these things need to be looked at. They all affect how well we can do our jobs. The bottom line here is if we’re going to ask our people to go in and do a job, then we need to back them when things go sideways. And if we’re going to ask them to do a job, we need to resource them and equip them so that we can see it through to the end,” he urged.

This is all the more important because access to local resources can be problematic in theaters like Afghanistan. In the case of the interrogation that led to the Army investigating his unit, Hill mentioned that he was unable to share some of the intelligence he had on the suspected enemy spies with Afghan police officers and had to contend with the possibility that some of them were compromised enemy agents. He noted that the danger of insider threats has proven to be far worse than originally estimated.

Hill warned that working with kid gloves in such treacherous environments, in a type of warfare which relies very heavily on timely and reliable intelligence, is incredibly dangerous. In his own case, he was accused of war crimes and “psychological torture” for merely perpetrating a ruse designed to frighten his high-value prisoners into divulging vital information. In essence, he tricked these prisoners into thinking their less valuable comrades had been taken outside by American troops to be beaten and shot, when, in truth, none of them suffered more than a hard slap.

“The lawyers are running the war,” he complained. “That’s part of the problem here.”

Hill described himself as a “fourth-generation veteran” whose great-grandfather died from wounds suffered during World War I.

“My grandfather served in the Navy during WW2. My dad was an infantryman, and I’m an infantry – was an infantry officer,” he said. “I went to West Point, branched infantry, became a Ranger, airborne qualified, served in Korea, Iraq, and then Afghanistan, which is where the book is set. My time in Iraq was spent as a combat adviser. I fought alongside the Kurds and the Peshmerga, fought from just south of Mosul all the way down to Ramadi during the surge in Iraq.”

Hill enthusiastically agreed with critics who say media bias and narrative-driven journalism have distorted the true stories of Afghanistan and Iraq.

“This book Dog Company is full of examples of that and full of examples of a lot of the politically driven rules of engagement-type stuff that we just talked about,” he told Marlow.

“There is a story in the book, one of the chapters about two-thirds of the way in, where we receive an SOS call from a New York National Guard unit that gets caught up in a valley called Tangi Valley,” he offered as an example.

“We had this sort of IM chat capability from vehicle to vehicle, so these guys are about 45 minutes away in the valley, and we get this SOS chat: ‘Hey, we’re in trouble. Come give us a hand if you’re nearby or available.’ So we load up, move out to those guys, not expecting to do so on that day because we had other operations going on,” he recalled.

“We show up, their vehicles are burned through the asphalt into the bedrock. There are uniform items strewn about the battlefield. There are shell casings all over the place. Soon after, a special operations unit shows up on the ground with pictures of two guys and says, ‘Hey, we’ve got two New York National Guardsmen missing in action right now. We’ve got to go find their bodies. We’re not sure if they’re dead or alive,’” he continued.

“That mission turns into a hunt, a search for these two guys. Long story short, our unit – my guys, Dog Company – finds one of the guys in a field some distance away. His arms had been hacked off. He’s naked. His uniform has been ripped off. His heart has been cut out, or at least that’s what we suspect because there is a hole in his chest right where his heart should be. At this point in time, we had a lot of assets in the air, and we were getting reports that his fingers were being sold in the local bazaars as war trophies.”

“My guys are the guys on the ground that are sifting through all this crap, and I find out some number of weeks later that what’s reported in the AP is that three National Guard soldiers were killed in action in Afghanistan in this area. Here are their ages. Here are their ranks. Here are their names. Killed in an I.D. ambush. End of story. No further comment,” said Hill.

“Part of the problem here is that the American people don’t know what we’re up against,” he contended. “They don’t know how barbaric and savage the enemy that we’re dealing with is, and the government has been hiding this from us. It really changes your perspective when you understand what you’re really dealing with. It changes the sense of urgency that you have. It changes what you’re willing to do to overcome such a barbaric enemy. Unfortunately, the American people have had a lot of this stuff repressed and hidden from them.”

Hill said the Obama administration was “a good example of the type of mindset and people that have pushed us more in the direction of being too P.C. and over-politicizing the military and the government at large.”

“The folks that have been advocates and have really come to the aid of Dog Company and other stories like ours, are folks like United American Patriots,” he added. “They’re an organization that is working to push the current administration, and has for past administrations, to conduct full reviews of the Uniform Military Code of Justice, to review the laws of warfare versus the rule of law, which is what we’re trying to push overseas.”

“You can’t fight a counterinsurgency, you can’t fight combat, with the same rules and restrictions that you police your own First World country with,” he argued. “There’s an inevitable conflict there between what we should be subscribing to in terms of law of warfare, which gives commanders a lot more latitude on the battlefield to discern and make decisions that they need to, given the realities on the ground – versus trying to push this agenda of, ‘Hey, we rule with police in a highly progressive Western civilization; let’s try to apply that rule of law to a fifth- or sixth-world country.’ It just doesn’t work.”

Marlow asked Hill to clarify just what the government has done to prevent publication of his book.

“There’s a case that’s central to this book. This book is tragic, but it’s also unfortunately very entertaining,” Hill observed. “The feedback that we’ve gotten is that when people pick it up, from the first chapter, they can’t put it down. The reason for that is it has a number of really neat elements to it. It’s sort of a cross between Band of Brothers and that sort of combat action and brotherhood, and then also it ends and sort of culminates with a court hearing, if you will, action. It’s sort of a cross between Band of Brothers and A Few Good Men.”

“The case central to the story was kicked off by an investigation which led to a hearing. The findings took that investigation and hearing – an Article 32 hearing, for those of your audience that are familiar with military law – the findings were written by an investigating officer who sort of serves as a judge, over what is equivalent to a civilian grand jury proceeding,” he explained.

“My higher command at that time fought to – and I didn’t know this – they conspired to make that set of findings an ‘incomplete record’ through a technicality, to make it unavailable through the Freedom of Information Act to the American public. From the very beginning, the findings were stifled and masked by the government to try to prevent the American public from knowing what really happened to Dog Company in Afghanistan in 2008 and 2009,” he charged.

“If you flip through the book, you’ll notice that there are a number of redactions in the book,” Hill added. “We submitted the book to the Office of Security Review at the Pentagon. They advertise that they can turn a book around in a month. They’ve got a whole office and staff dedicated to doing this. They got back to us once they received the book and said, ‘Hey, you’re book’s a little long’ – our book’s about 420 pages; it’s got a bit of a presence to it – and they said, ‘It’s gonna take us two months.’ It took them a year to get their review done, and when we got the book back, by that point in time, we had hired subject matter experts in counter-intel and intelligence to review it, and they argued that 90 percent of the redactions that the government had made were already in federally funded websites.”

Breitbart News Daily airs on SiriusXM Patriot 125 weekdays from 6:00 a.m. to 9:00 a.m. Eastern.

Listen to the full audio of the interview above.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.