ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. (AP) — A push for more states to restrict law enforcement from seizing cash and property from people during traffic stops is aligning the likes of conservative billionaire Charles Koch and the American Civil Liberties Union, known for championing many liberal causes.

Both contend the practice known as civil asset forfeiture has come to represent an overused law enforcement tactic that violates citizens’ private property rights, especially when there’s insufficient evidence of a crime.

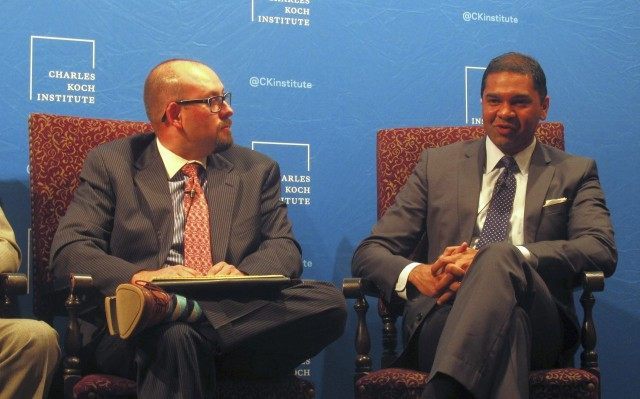

The unusual common ground between the two groups — who are opposed on most political issues — brought them together on the same stage Wednesday night as the Charles Koch Institute hosted a forum in Albuquerque to discuss a New Mexico law enacted this year that reins in the ability of police to seize property. They consider the law a national model for reform because it requires authorities to obtain a criminal conviction before allowing officers to seize a person’s property.

For Koch and his conservative think tank, the spotlight on civil asset forfeiture comes as his Koch Industries makes a broader push to overhaul the criminal justice system and lobby for changes, like legislation that would adjust federal sentencing guidelines and reduce prison populations. Those efforts have aligned Koch — best known with his brother David for pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into backing conservatives and libertarian causes — with rivals on the left who are staunch supporters of President Barack Obama.

“You know something’s a good idea if everyone except law enforcement agencies that are profiting from these programs believes this is a good idea,” said Steven Robert Allen, a policy director for ACLU in New Mexico.

New Mexico now has one of the toughest laws in the country in restricting how and when police can take people’s assets during traffic stops. Before it took effect in July, law enforcement could seize items from people without charging or convicting them if they could present convincing evidence the property was related to a crime. The burden of proof was placed on the property owner to have the assets returned.

Similar practices are still the case in most states and under federal law.

In one case several years ago, a 60-year-old man and his grown son sued for the return of $17,000 in cash confiscated during a traffic stop in Albuquerque while en route to Las Vegas. Local police pulled them over in their rental car for an improper lane change and notified U.S. Homeland Security officers, who seized the cash.

Stephen Skinner and his son Jonathan Breasher planned to spend the money during their trip and to help a relative with house repairs. They were never charged with a crime. In 2012, the ACLU of New Mexico reached a settlement with the U.S. government to reclaim the money on behalf of the men.

Now, law enforcement in New Mexico must wait to claim cash and auction off seized assets until prosecutors win a criminal conviction against a defendant. Minnesota and Montana have laws similar to New Mexico’s.

Law enforcement officials defend civil asset forfeiture as a way to weaken lucrative criminal operations while funding crime-fighting efforts by auctioning off assets seized during searches and investigations.

San Juan County Sheriff Ken Christesen in northern New Mexico said his agency never profited from seized items unless a person was convicted of a crime. Still, he believes the new law is costly and flawed — a point with which the New Mexico Sheriffs Association agrees. The measure gives criminals an edge, allowing drug syndicates to build up assets, Christesen said.

“The end result of this is the cartels are going to ramp up their money laundering and cash exchanges in the state of New Mexico tenfold,” he said.

The Charles Koch Institute and the ACLU see it differently, believing the laws violate people’s rights and create mistrust of law enforcement.

In New Mexico, money from property seized during drug busts and investigations provided law enforcement agencies with roughly $24.5 million in spending since 2008, according to the Koch Institute.

“Right now, there’s a real problem of mistrust between communities and law enforcement. There are a lot of reasons for that and I think civil asset forfeiture policies are part of it,” said Vikrant Reddy, a senior researcher at the Charles Koch Institute. “This is an exceptionally dysfunctional aspect of the criminal justice system.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.