Police officers in Brazil’s Espirito Santo state have finally returned to work after a ten-day strike that left the city in a state of anarchy, with more homicides recorded during the strike than during the entire month of February in 2016.

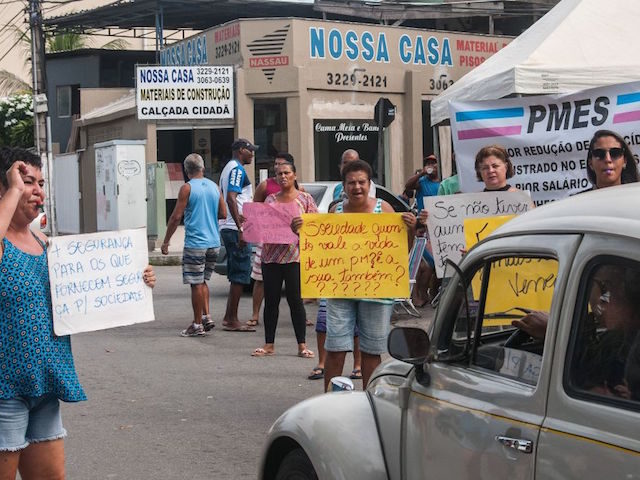

According to the Brazilian Globo media network, the state recorded 147 violent deaths, 200 cases of larceny crimes (robbery or burglary), and over $96 million in business losses in the ten days during which the police did not patrol the streets. Brazilian law does not allow police to go on strike, so their families instead protested in front of police facilities, preventing police from using patrol cars or leaving their facility.

State authorities announced on Tuesday that 161 police officers would lose their jobs over the incident. 703 police officers are currently under investigation for either violating the terms of their employment or engaging in criminal activity. Those accused of criminal negligence in conducting police work face between eight and twenty years in prison.

Police initially announced that they had reached a deal with the government to return to work on Saturday, though most officers did not do so. By Sunday, one thousand police officers had returned to their patrols. A day later, that number had nearly doubled to 1,743, according to Globo’s G1. Espirito Santo normally has 2,000 officers patrolling its streets at a time, according to the outlet. Reuters reports that Brasilia was forced to deploy 4,000 military police officers, who operate nationally in times of crisis, to replace the officers in the state who had refused to do their job.

The family of police officers began preventing them from doing their work on February 4, arguing that the salaries of Espirito Santo officers, averaging $847.09 monthly, were the lowest in the nation, and not enough to sustain a family. Immediately after the strike began, the homicide and other violent crime rates skyrocketed. Three days into the strike, officials documented a 650-percent increase in homicides alone and a 1000-percent increase in crime generally.

The crime wave forced businesses, schools, and health centers in the capital, Vitória, to shut down to prevent violent attacks. Thugs burned public transportation vehicles and robbed any pedestrians who dared leave their homes. “What is happening in Espirito Santo is open extortion,” Espirito Santo Governor Paulo Hartung said last week. “It is the same thing as kidnapping citizens and asking for ransom. Ransom cannot be paid, neither for ethical reasons nor without violating the Fiscal Responsibility law.”

“We supported the strike the first few days. But it has to end, there’s been too much violence,” Vitória resident Alexandre Gois told Al Jazeera this week. “The police got what it needed, to show the population it depends on them.”

The criminal investigations into the police officers is a measure to prevent a similar situation in the future. With the police strike in Espirito Santo over, federal officials appear to be eyeing the next potential protest in the much larger state of Rio de Janeiro.

Brazilian President Michel Temer announced Tuesday that he would deploy 9,000 Military Police officers to Rio de Janeiro through the end of the annual Carnival festival. Defense Minister Raul Jungmann called the move “pre-emptive” in light of minor protests in the region. In Rio de Janeiro’s case, local officials describe the protesters as “anarchists” looking to cause discord as legislators attempt to approve new austerity measures in a state that cannot currently pay its police.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.