The Zika virus outbreak is exposing a ghastly secret that the environmentalist movement wants hidden, even if the cost is more Zika-babies.

Zika is spread primarily by mosquitoes, so killing the mosquitoes is the best way to keep the virus from spreading. The major outbreak areas in South America have long histories of struggling with mosquito control. One reason is their inability to obtain effective pesticides, principally the mosquito-killer DDT, due to environmentalists’ fierce and utterly faked junk-science.

The DDT ban was the first epic victory of environmentalist junk science, so the Greens will never walk it back, no matter how many people sicken and die because of their “triumph.”

With tens of millions of people already killed by malaria unnecessarily, a few thousand Zika victims will add little to the butcher’s bill.

To this day, news organizations cite their DDT hoax as if it was true. But it wasn’t — the pesticide caused none of the problems laid at its feet, including the infamous thinning of bird shells alleged by the 1962 book Silent Spring. This was known at the time, as reputable scientific research knocked down the anti-DDT allegations … only to be overridden by political considerations.

Dr. Robert Zubrin, author of a recent book on junk science, succinctly summed up the DDT saga in a National Review article, calling for the return of the much-maligned, highly effective pesticide:

The role of DDT in saving half a billion lives did not positively impress everyone, however. On the contrary, many environmentalist leaders were quite upset. As Alexander King, the co-founder of the Club of Rome, put it in 1990, “my chief quarrel with DDT in hindsight is that it has greatly added to the population problem.” Of course, such reasoning would carry little appeal to the American public.

Much better ammunition was provided by Rachel Carson, who in her 1962 book, Silent Spring, made an eloquent case that DDT was endangering bird populations. This was false. In fact, by eliminating their insect parasites and infection agents, DDT was helping bird numbers to grow significantly. No matter. Using Carson’s book and even more wild writing by Population Bomb author Paul Ehrlich (who in a 1969 Ramparts article predicted that pesticides would cause all life in the Earth’s oceans to die by 1979), a massive propaganda campaign was launched to ban DDT.

In 1971, the newly formed Environmental Protection Agency responded by holding seven months of investigative hearings on the subject, gathering testimony from 125 witnesses. At the end of this process, Judge Edmund Sweeney issued his verdict: “The uses of DDT under the registration involved here do not have a deleterious effect on freshwater fish, estuarine organisms, wild birds, or other wildlife. . . . DDT is not a carcinogenic hazard to man.”

No matter. EPA administrator William Ruckelshaus (who would later go on to be a board member of the Draper Fund, a leading population-control group) chose to overrule Sweeney and ban the use of DDT in the United States. Subsequently, the U.S. Agency for International Development adopted regulations preventing it from funding international projects that used DDT.

Together with similar decisions enacted in Europe, this effectively banned the use of DDT in many Third World countries. By some estimates, the malaria death toll in Africa alone resulting from these restrictions has exceeded 100 million people, with 3 million additional deaths added to the toll every year.

The enthusiasm of people who thought the Earth was overpopulated for banning life-saving DDT really should have been a tip-off to the true agenda behind the ban. The population-bomb crowd definitely got what it wanted. Dr. Wenceslaus Kilama, chairman of the Malaria Foundation International, once compared the death toll from Africa’s malaria epidemic to “loading up seven Boeing 747 airliners each day, then deliberately crashing them into Mt. Kilimanjaro.”

Here we are again, with a disease much less deadly than malaria, but nevertheless of great concern to people around the world, and we’re prevented from using our most effective weapons against the insects that spread it.

That’s because the environmentalist movement would never recover its clout if its DDT victory is revealed as a contributor to the Zika disaster. That might cause people to look at the false “settled history” of the 1970s anti-DDT campaign. Too many of the methods used in other junk-science crusades were honed against DDT, and Silent Spring is too important as a cornerstone of environmentalist mythology.

“Will the environmental bureaucrats continue to block the use of essential life-saving pesticides, and thereby cause an even worse global catastrophe that will go on for generations?” asks Dr. Zubrin, already knowing the answer.

The arguments against bringing DDT back to fight Zika instantly spin off into speculation and hypothesis. For example, Newsweek cites Joe Conlon of the American Mosquito Control Association delivering the hardy perennial argument that DDT might not work as well today, because some strains of mosquitoes might have developed a resistance to it, or they might become resistant if we begin spraying them again. They might even develop improved resistance to other pesticides after exposure to DDT.

Those sound like hypotheses to be tested, not reasons to avoid trying everything we can. Words like “might,” “could,” “may,” and “probably” are peppered through every paragraph of the Newsweek anti-DDT story.

Conlon also sets up the classic false choice between bathing South America in billowing clouds of DDT, or pursuing more holistic solutions, such as a “change in culture” that would make residents of Zika outbreak areas more aggressive about eliminating pools of standing water, depriving mosquitoes of easy breeding grounds. That sounds like good advice, but why not use our most effective pesticides in a carefully controlled manner, to reduce the immediate threat while waiting for that “change in culture” to take hold?

Some postulate that the pesticides that are being used in places like Brazil are responsible for the birth defects blamed on the Zika virus. The more extreme versions of this theory posit that Zika is essentially a hoax concocted to hide the perfidy of spray-happy agricultural concerns in South America — the virus is real enough, but it doesn’t cause any of the horrible secondary effects linked to it. If the pesticides currently used in the area are dangerous and ineffective, a dramatic change in strategy is worth considering.

As to the cause of those birth defects, the official position of the World Health Organization, according to its chief Margaret Chan, is that a WHO emergency committee agreed “a causal relationship between the Zika infection during pregnancy and microcephaly is strongly suspected, though not scientifically proven.” The number of severe Guillain-Barre syndrome reactions in Zika patients is also a matter of serious concern.

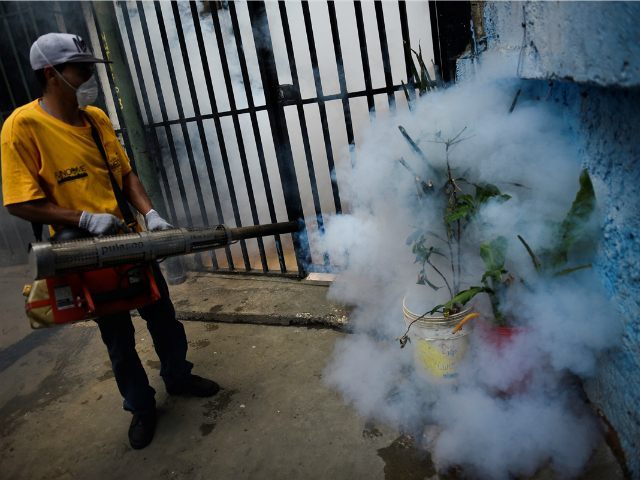

Given the lack of a vaccine for Zika, and the enduring uncertainty about its effects, fighting the mosquito carriers is a key part of any containment strategy. Such is the case in Florida, where a state of public health emergency has been declared in several counties.

Reuters notes that “the types of mosquitoes carrying the Zika virus, Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, are common in Florida, where mosquito season is year-round, and along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, including Houston.”

There are already signs of Florida mosquito control departments stepping up their efforts, with Hillsborough County “paying workers overtime as it steps up spraying, mosquito monitoring, and misting in the area of the home of someone who had Zika.”

The Reuters piece mentions plans to educate people about the importance of removing standing-water mosquito breeding grounds — the “change in culture” recommended above for the outbreak areas – while also expanding pesticide deployment. Northern states like Illinois and New York have a little respite from the Zika threat, due to the dormancy of mosquitoes in winter, but will soon have to think about intensifying their own control programs, especially if more Zika-infected travelers return home.

Interestingly, Reuters specifically mentions the “decline in use of pesticides such as DDT,” along with the increase in international travel, as factors behind notorious outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases like dengue, chikungunya, the West Nile virus, and our old nemesis malaria.

At the moment, America, Canada, and Europe are facing very small numbers of Zika patients, with the vast majority of the infections acquired during travel to the outbreak regions.

But South America is looking at up to four million cases this year, potentially translating to thousands of cases of microcephaly and neurological disorders. Effective vaccines are estimated to be at least three years away. The advice given to avoid Zika’s effects consists of suggestions like “don’t get pregnant.”

An ounce of prevention will be worth many pounds of the cure that doesn’t exist yet, and the only prevention available at the moment involves killing the mosquitoes, as effectively as possible.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.