The European Union (EU) is considering tax hikes as well as slashing farmers’ subsidies and Eurocrat wages to meet a huge €20 billion shortfall after it loses the UK’s contribution to the bloc.

“The Brexit gap will be financed by a mix of cuts, shifting expenditure, saving and some new sources of money,” explained Günther Oettinger, the EU’s budget commissioner, on his blog yesterday.

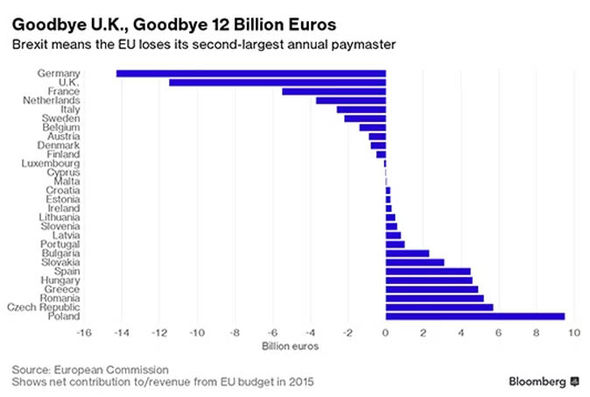

The commissioner had published a 40-page policy paper on “the future of EU finances”, addressing hard questions around how to make up for the UK’s massive net contribution to the bloc – the second largest after Germany.

After the €3 billion rebate secured by former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and the receipts of EU farm or regional subsidies, Britain’s net contribution amounts to about 8 per cent of the Brussels budget.

“The withdrawal of the United Kingdom will signify the loss of an important partner and contributor to the financing of EU policies and programmes,” the policy paper states.

Without the UK’s cash, there will be an annual gap of €10 billion to €11 billion in the EU budget, Mr. Oettinger said, adding that the need to finance new initiatives in areas such as defence and security meant “the total gap could therefore be up to twice as much”.

A proposal to “reduced direct payments” under the EU Common Agricultural Policy – which make up 39 per cent of spending – is likely to horrify French farmers, and would require national governments to pick up the burden of farm subsidies.

There are also likely to be freezes made to Eurocrats’ notoriously generous wages and employee perks.

Additionally, as The Times points out, the funding gap could cause divisions and tensions in the bloc.

Those that make a net contribution – Germany, France, Italy, Austria, the Netherlands, and Denmark – are likely to push for cuts, which those that take out more than they put in will be hesitant to do.

Further, there is a controversial proposal to make regional funding conditional on meeting the “rule of law”, rather than targeting it at the poorest regions.

This is set to alarm Greece and Italy – which struggle to meet EU economic directives – as well as Hungary and Poland, which are currently battling the EU’s forced migrant quota policy.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.