SACRAMENTO, Calif. (AP) — Three years after California voters passed a ballot measure to raise taxes on corporations and generate clean-energy jobs by funding energy-efficiency projects in schools, barely one-tenth of the promised jobs have been created, and the state has no comprehensive list to show how much work has been done or how much energy has been saved.

Money is trickling in at a slower-than-anticipated rate, and more than half of the $297 million given to schools so far has gone to consultants and energy auditors. The board created to oversee the project and submit annual progress reports to the Legislature has never met, according to a review by The Associated Press.

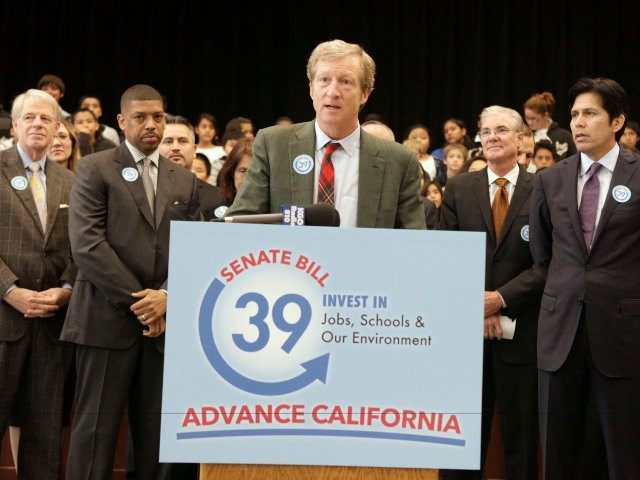

Voters in 2012 approved the Clean Energy Jobs Act by a large margin, closing a tax loophole for multistate corporations. The Legislature decided to send half the money to fund clean energy projects in schools, promising to generate more than 11,000 jobs each year.

Instead, only 1,700 jobs have been created in three years, raising concerns about whether the money is accomplishing what voters were promised.

“Accountability boards that are rubber stamps are fairly common, but accountability boards that don’t meet at all are a big problem,” said Douglas Johnson, a state government expert at Claremont McKenna College in Southern California.

Democratic and Republican lawmakers called for more oversight Monday and requested a legislative hearing to examine the program.

“We should hold some oversight hearings to see how the money is being spent, where it is being spent and seeing if Prop. 39 is fulfilling the promise that it said it would,” said Assemblyman Henry Perea, D-Fresno.

The State Energy Commission, which oversees Proposition 39 spending, could not provide any data about completed projects or calculate energy savings because schools are not required to report the results for up to 15 months after completion, spokeswoman Amber Beck said.

Still, Beck said she believes the program is on track. The commission estimates that based on proposals approved so far, Proposition 39 should generate an estimated $25 million a year in energy savings for schools.

Not enough data has been collected for the nine-member oversight board of professors, engineers and climate experts to meet, she said.

The AP’s review of state and local records found that not one project for which the state allocated $12.6 million has been completed in the Los Angeles Unified School District, which has nearly 1,000 schools. Two schools were scheduled this summer to receive lighting retrofits and heating and cooling upgrades, but no construction work has been done on either site, LAUSD spokeswoman Barbara Jones said.

The office of Senate President Pro Tem Kevin de Leon, D-Los Angeles, previously estimated LAUSD would save up to $27 million a year on energy costs; projects proposed by the district so far would save only $1.4 million.

De Leon, the primary booster of Proposition 39 in the state Legislature, said in a statement Monday that the measure is already successful and it is too soon to assess its implementation.

“Most school districts are either in the planning phase or are preparing to launch large-scale, intensive retrofit projects that will maximize benefits to students, school sites and the California economy,” de Leon said in a joint statement with the initiative’s chief supporter, billionaire investor and philanthropist Tom Steyer. He funded the initiative campaign with $30 million of his money.

School district officials around the state say they intend to meet a 2018 deadline to request funds and a 2020 deadline to complete projects. They say the money will go to major, long-needed projects and are unconcerned schools have applied for only half of the $973 million available so far, or that $153 million of the $297 million given to schools has gone for energy planning by consultants and auditors.

“If there’s money out there, we’re going for it,” said Tom Wright, an energy manager for the San Diego Unified School District, which has received $9.5 million of its available $9.7 million.

Leftover money would return to the general fund for unrestricted projects of lawmakers’ choosing.

The proposition is also bringing in millions less each year than initially projected. Proponents told voters in 2012 that it would send up to $550 million annually to the Clean Jobs Energy Fund. But it brought in just $381 million in 2013, $279 million in 2014 and $313 million in 2015.

There’s no exact way to track how corporations reacted to the tax code change, but it’s likely most companies adapted to minimize their tax burdens, nonpartisan legislative analyst Ken Kapphahn said. He also said the change applies to a very small number of corporations.

Steyer’s team sought to distance him from the measure’s implementation, saying the billionaire wanted to respect the legislative process.

It’s undeniable that Proposition 39 has created a disappointing number of jobs, said Kirk Clark, vice president of the California Business Roundtable, which opposed the measure but did not aggressively lobby against it.

“We’ve got a long track record in California of over-promising green jobs and under-delivering,” said Clark, who also expressed concern that most of the jobs created so far appear to be consulting positions.

Neither the Energy Commission nor Tim Rainey, director of the California Workforce Investment Board, could identify the types of jobs created by Proposition 39 projects. They said that information would be available when the oversight board meets for the first time, likely in October or November.

Clark also noted that nearly half the approved projects have been lighting retrofits, which don’t create as many jobs as work-intensive projects such as replacing heating and air conditioning systems.

Schools often prioritize lighting projects because they work well with the Energy Commission’s formula, which requires schools to save at least $1.05 on energy costs for every dollar spent. The Energy Commission said its jobs number is based on dollars spent and doesn’t take the type of project into account.

Johnson said the slow results show the oversight board should have gotten involved much earlier.

“They should have been overseeing all stages of this project, not just waiting until the money’s gone and seeing where it went,” Johnson said.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.