Some of America’s greatest innovations have been born from our most devastating tragedies. Such was the case in the Great War.

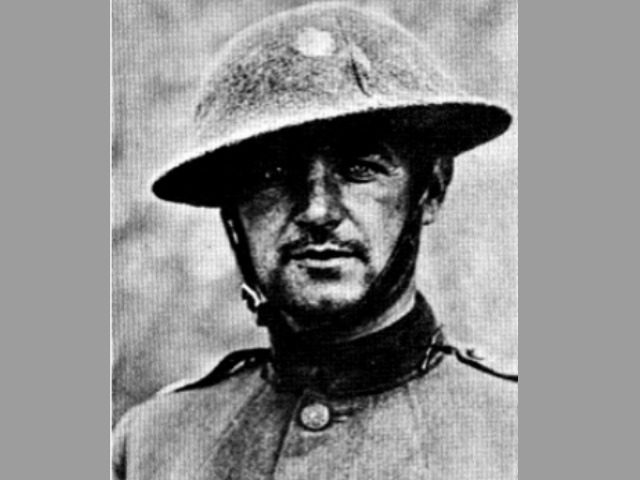

One hundred years ago, the United States rushed troops to the trenches of the Western Front in a desperate attempt to stop the Central Powers from conquering Europe. One of the soldiers shipped over to France was William Donovan, a 35-year-old lawyer and officer in the New York National Guard. He witnessed firsthand the horrific casualties caused by sending men over the top to make direct frontal assaults on enemy positions — and what he saw forever changed him.

Within days of arriving at the front lines in March 1918, Donovan and the other Irish Americans of the “Fighting 69th” found themselves in the Rouge Bouquet, a wooded area that the U.S. was using for training purposes. It was supposed to be a quiet sector, but on March 7, the Germans launched an overwhelming artillery barrage on the Rouge Bouquet.

At the time, Donovan, who commanded the 69th’s 1st Battalion, happened to be visiting the 2nd Battalion’s command post, a hardened dugout 40 feet below the surface, when a well-targeted shell obliterated the position. Tons of dirt, stone and debris cascaded down, burying 21 men alive.

Donovan organized a frantic rescue effort. He and others shoveled feverishly in an attempt to free their comrades. But the continued shelling and constant mudslides stymied their efforts. In the end, they rescued only two and recovered the dead bodies of five more men.

Afterward, Donovan received the French Croix de Guerre in honor of his efforts, and soldier-poet Joyce Kilmer wrote a poem honoring the fallen. But the most significant result of the episode may have been the lingering impact it had on Donovan himself.

A portion of Donovan’s World War I experience is retold in my new bestselling book, The Unknowns: The Untold Story of America’s Unknown Soldier and WWI’s Most Decorated Heroes Who Brought Him Home. Recently released, the book follows eight American heroes who accomplished extraordinary feats in the war’s most important battles. As a result of their amazing bravery, these eight men were selected to serve as Body Bearers at the ceremony where the Unknown Soldier was laid to rest at Arlington Cemetery.

Born New Year’s Day, 1883, in Buffalo, New York, Donovan came from a staunchly Catholic Irish family. He attended several different universities and was a standout football player. He graduated from Columbia Law School in 1907. In 1912, the young lawyer joined the National Guard and later went to the Mexican border to help track down Pancho Villa before eventually shipping out for World War I.

His brave actions at Rouge Bouquet were far from his last during the Great War. In the fall of 1918, he led his men in an offensive against the famed Hindenburg Line in the Battle of the Meuse-Argonne. The frontal assault nearly cost him his entire unit.

Before the battle was over, Donovan led another attack, this time near the town of Landres-et-Saint-Georges. After seeing so many of their comrades cut down in ill-fated charges, the men under his command were understandably hesitant to launch an assault. He found the only way to get his inexperienced men to advance was to lead from the front. To bolster their morale, he stayed on the front lines as the situation worsened and delivered his orders to the various units in person.

That decision proved costly. “I had walked to the different units and was coming back to the telephone when smash, I felt as if somebody had hit me on the back of the leg with a spiked club,” he later wrote. “I fell like a log, but after a few minutes managed to crawl into my little telephone hole.”

Despite having taken a bullet to the right knee, Donovan refused to leave the battlefield. He stayed with his men, encouraging them by example to fight on. His ability to carry on while in tremendous pain earned him the nickname “Wild Bill.”

He received the Medal of Honor for his efforts in the Meuse-Argonne, and the citation read:

Lt. Col. Donovan personally led the assaulting wave in an attack upon a very strongly organized position, and when our troops were suffering heavy casualties he encouraged all near him by his example, moving among his men in exposed positions, reorganizing decimated platoons, and accompanying them forward in attacks. When he was wounded in the leg by machine-gun bullets, he refused to be evacuated and continued with his unit until it withdrew to a less exposed position.

His personal experiences with trench warfare convinced Donovan of the futility of current military tactics. His WWI involvement also inspired him to pursue public life. After the war, he served on numerous commissions and traveled abroad extensively.

When World War II broke out, President Franklin Roosevelt realized that he needed someone to coordinate the nation’s nascent intelligence efforts, and the natural choice for the job was Donovan. He headed up the Coordinator of Information (COI), which later became the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

In his role as the nation’s spymaster, Donovan had the opportunity not only to reshape the country’s intelligence service but also to build its modern special operations forces. Looking back upon American history, his experience in the trenches and other special operations at the time, Donovan devised a novel form of “shadow warfare,” where he combined special operations with intelligence and psychological operations.

Practically overnight, he created the country’s modern special operations from scratch. He placed extraordinary individuals into positions that ultimately created the precursor for the U.S. Navy SEALS (the OSS Maritime Unit) and the U.S. Army Green Berets (OSS Operational Groups and Jedburgh Teams). Psychological operations groups, given the rather prosaic name “Morale Operations” (MO), also operated in the field. Donovan’s ideal candidate for these positions was a “PhD who could win a bar fight.”

Even as America’s top spy, Donovan led from the front and went along on most of the country’s major invasions, including D-Day at Normandy. He became the only American to have received the country’s four most prestigious decorations: the Medal of Honor, the Distinguished Service Cross, the Distinguished Service Medal and the National Security Medal.

He never forgot the lessons learned from the loss of life he witnessed in the trenches, and he did everything in his power to use better strategy to reduce casualties. Admiral Louis Mountbatten later said, “I doubt whether any one person contributed more to the ultimate victory of the Allies than Bill Donovan.”

Upon Donovan’s death in 1959, President Eisenhower summed up Donovan’s life, saying, “What a man! We have lost the last hero.”

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of eleven books. The Unknowns: The Untold Story of America’s Unknown Soldier and WWI’s Most Decorated Heroes Who Brought Him Home is his newest bestseller. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and speaks often on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and for documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickkODonnell.com @combathistorian

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.