Populist-Nationalism, Right and Left

Here’s a headline that a lot of people—especially among the entrenched elite—won’t want to see: “2017 Was the Year of False Promise in the Fight Against Populism: The populist wave seems like it may have crested. The data proves otherwise.” In other words, the populists are still on the march. Uh oh.

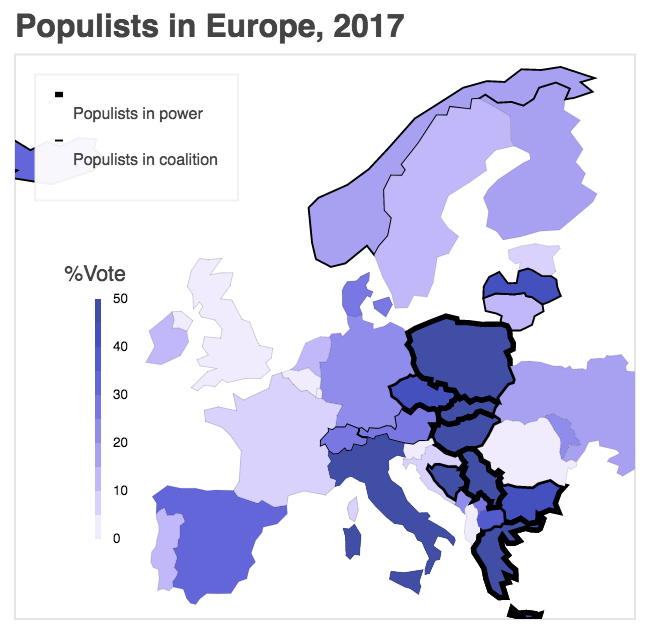

Screenshot of map showing election results of 102 populist parties across 39 European countries (Photo credit: European Populism: Trends, Threads, and Future Prospects)

That headline appeared in Foreign Policy magazine, a publication not on the top of many populist reading lists. The two authors, Yascha Mounk and Martin Eiermann, are both associated with the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. Blair, as we all recall, was the prime minister of the United Kingdom for a decade; he was, and is, a devout apostle of globalism.

So the co-authors come at their topic not to praise populism but, rather, to warn against it; as they write, it’s been “a scary couple of years,” what with Brexit and the election of Donald Trump. And while they take note of high-ranking observers who have argued that populism is ebbing—one such is the conservative pundit Charles Krauthammer, who opined in April, “The populist wave has crested, soon to abate”—they disagree with that conclusion.

Indeed, just in October, the 31-year-old Sebastian Kurz was elected chancellor of Austria; he holds populist-nationalist views on immigration that can only be described as Trumpian. As the authors explain,

Populism is now the predominant form of government in a huge, populous, and strategically crucial part of Central Europe. It is now possible to drive from the Baltic Sea all the way to the Aegean without once leaving a country ruled by a populist.

Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz listens to questions during a joint media conference with European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker at EU headquarters in Brussels on Tuesday, Dec. 19, 2017. (AP Photo/Virginia Mayo)

Indeed, as this writer has observed, it’s a paradox that the populist-nationalists are strongest in the countries that were once dominated by Soviet-imposed communism; in reaction to that harsh experience, they are now on the right.

Moreover, Mounk and Eiermann continue, even in those countries where populists have not taken power, their influence is still being felt:

To stave off the competition from the extremes, traditionally moderate parties . . . have recently lurched to the right.

The most spectacular example of moderates lurching right is in France. Earlier this year, Emmanuel Macron was elected president of that country on a sort of neo-Blair or Obama platform, defeating the hardcore populist-nationalist Marine LePen.

Yet since taking office, Macron has shifted to starboard, especially on immigration; here’s an indicative Associated Press headline from December 26: “Macron gets tough as France struggles to deal with migrants.” As the AP put it, his goal is to “get migrants off France’s streets and out of forest hideouts by year’s end.” And even if he doesn’t meet that deadline, he’s trying: “Macron’s government is now tightening the screws: ramping up expulsions, raising pressure on economic migrants and allowing divisive ID checks in emergency shelters.”

To be sure, Macron is still no kind of populist; he recently celebrated his birthday at Chambord, the deluxe chateau of King Francois I, and he has even compared himself to the Roman god Jupiter. Okay, so that’s the Macron style; as a former investment banker, he’s as upper crust as they come. Yet still, on at least some gut issues of substance, he has tacked to the right, perhaps with an eye to fending off a renewed challenge from LePen and her proletarian immigration hawks.

Yet as the Foreign Policy co-authors note, not all of the new European populists are on the right; the phenomenon can also be seen on the left. For instance, the leftist populist surge has been profound in economically depressed Greece, where anti-establishment figures on the left, vowing a new deal for Greeks, have been winning elections.

So we can see: Europe is brimming with Donald Trump-types, as well as Bernie Sanders-types—and oh yes, quite a few Nigel Farages. These disparate leaders might not agree on much, but they do agree that the elites—especially the transnational elites who run outfits such as the European Union—have done a bad job at governing and that the little guy should get a better break.

Indeed, the populist-nationalist wave is broader than just in Europe and America. In India, for example, the same impulses swept the insurgent Narendra Modi into the prime ministership. And now, too, the populist unrest in Iran.

In the meantime, among the elite, some are starting to take note of all this upswell. One such is the CEO of Microsoft, Satya Nadella, who was himself born in Hyderabad, India, although he has lived in the U.S. for decades. In a December 25 interview with Bloomberg Businessweek, Nadella declared,

We can’t say, “Well, this nationalist movement of populism is a passing phase.” We’ve got to deal with it as a phase that we’ve entered because the dividend of globalization hasn’t yielded more equitable growth for the world.

Using some distinctly Trumpian language, Nadella then applies populism to the whole wide world:

It’s America First in the U.S. It’s going to be Britain First in the United Kingdom. It’s going to be China First in China. That’s what the world will expect. No one is going to get elected to any country’s presidency or prime ministership by not talking about their country first.

President Donald Trump, left, reaches to shake hands with Satya Nadella, Chief Executive Officer of Microsoft, during an American Technology Council roundtable in the State Dining Room of the White House, Monday, June 19, 2017, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

We can note that Nadella’s words leave plenty of room for interpretation; that is, the question of what national policies are needed to put a country first is left unanswered. The only thing that’s non-negotiable, it would seem, is the idea of focusing on one’s own country’s interest, including national sovereignty and a no-nonsense attitude toward border security.

In other words, this is a bad time for an ambitious politician to be declaring, We should be citizens of the world!

2018 and 1848: Is There a Word for a 170th Anniversary?

If we step back from the headlines, we can see a broader trend in the world today: The decline of old authority.

That old authority included faith in institutions, especially international institutions. Yet people in America, and around the world, aren’t sure whom to trust anymore; they believe, with ample justification, that their leaders have let them down. And so for now, at least, they are putting their trust in themselves. That is, if the elites can’t be relied upon, well, the people themselves will have to figure it out, choosing new leaders who speak to them in a new language of solidarity. This is populism, and it blends into nationalism, because both “isms” are validated by the popular will.

Yet in fact, this populist-nationalist impulse isn’t so new: History has seen it before.

Back in 1848, Europe was dominated by kings and queens, emperors and tsars. All these royals formed their own kind of internationale; King Christian IX of Denmark, for example, was known as “the father-in-law of Europe,” because so many of his family members married into other European royal houses, from Britain to Spain.

Portrait of Christian IX, King of Denmark, by Hans Olrik (Public Domain / Wikimedia Commons)

Moreover, many of these crowned heads ruled over territories that had agglomerated into baroque geographical arrangements; that is, their boundaries paid no regard to the obvious demarcations of culture and language. They were in fact, multinational empires, held together by force, and little else.

The biggest of these multinational domains was the Austrian Hapsburg Empire, whose capital was Vienna. That realm sprawled across Central Europe, and while it was ruled by the German-speaking Hapsburg dynasty, no more than a quarter of the empire’s population spoke German; the rest spoke 17 other languages, plus innumerable local dialects.

As a result, while Austria was large, it was weak. That is, the populace didn’t have much in common, and certainly, few wanted to fight for Austria. The only thing that held the empire together was the autocratic power of the Hapsburgs. They were hardly tyrants, to be sure, and yet any sort of rule from Vienna became increasingly tenuous in light of the bubbling populist-nationalist passions in the far-flung provinces. (Indeed, today, the former Hapsburg territories are found within the borders of no less than a dozen countries, from Italy to Ukraine.)

And so we come, of course, to the obvious parallel: The Hapsburg Empire was its own version of the European Union. That is, the European Union today has many of the features of the Hapsburg Empire yesterday: the same polyglot nature, the same out-of-touch government—and the same populist-nationalist passions pulling it apart, nation by nation.

Things came to a boil in 1848. Riots and revolts erupted all over Europe, from Paris to Copenhagen to Warsaw, some 50 uprisings in all. The big idea was national self-determination—often for nations that didn’t yet exist because they had been submerged in someone else’s kingdom. That’s why 1848 is remembered as “the spring of nations.”

The rebels scored some immediate successes: The French monarchy was overthrown, for the second and last time. (Today’s Deplorables might be interested in knowing that the climactic events of the novel-turned-musical Les Misérables were set in 1830—that being a tragic Parisian forerunner to the victory of 1848.)

Painting of the battle at Soufflot barricades at Rue Soufflot on June 24, 1848, by Horace Vernet (Public Domain / Wikimedia Commons)

Yet elsewhere in Europe, the rebellions were put down. That is, when the smoke cleared, the royals were still in charge, at least for the time being.

And yet without a doubt, everything had changed: In 1848, the old authority of the crowned heads had fallen, and it couldn’t be restored. Over the coming years, the populist-national geyser was forcing a new arrangement within countries: typically, the royal rule continued, albeit with declining powers. In the meantime, an elected legislature of some kind, with rising powers, ushered in the essential elements of modernity, including delineated rights for citizens and workers, as well as the beginning of a social welfare system. After all, good nationalists must take good care of the nation.

And yet, even so, the old geographical lines continued to fade; new nations, based on common bonds, rose up, pulling together the fragments of some decaying empire. Thus Italy was united in 1861, Germany in 1871, and Romania in 1878, among others.

Now it’s easy to see the parallel with today: As we have seen, beginning in 1848, the populist-nationalists started to pull down the old order. And in our time, in Europe and around the world, a new set of populist-nationalists—animated by many of the same impulses, aiming at many of the same sort of targets—are doing the exact same thing.

So today, the bureaucrats of Brussels, dreaming of turning the European Union into an even greater empire, might recall the fate of the Hapsburg autocrats in Vienna after 1848. To put it bluntly, back then, dictates from a distant palace were no longer meekly accepted by local populations—and that’s what’s happening again.

Alas, there’s no word for a 170th anniversary—not that the EU would want to celebrate, of course, those long-ago empire-quaking events.

Yet even if the populist-nationalists of today don’t hold an anniversary party for 1848, their many movements will go on, guided by the same spirit. They won’t win every political contest, and yet they are winning enough of them, and as a result, they are reshaping Europe.

And so when the bicentennial of 1848 comes around in three decades, it seems inevitable that today’s EU will be unrecognizable.

Main Photo Credits (left to right): Giuseppe Garibaldi entering Naples in 1860 by Franz Wenzel Schwarz (Public Domain / Wikimedia Commons); Revolutionaries in Berlin waving revolutionary flags in March 1848, by Unknown (Public Domain / Wikimedia Commons); Lamartine in front of the Town Hall of Paris rejecting the red flag on February 25, 1848, by Henri Félix Emmanuel Philippoteaux (Public Domain / Wikimedia Commons)

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.