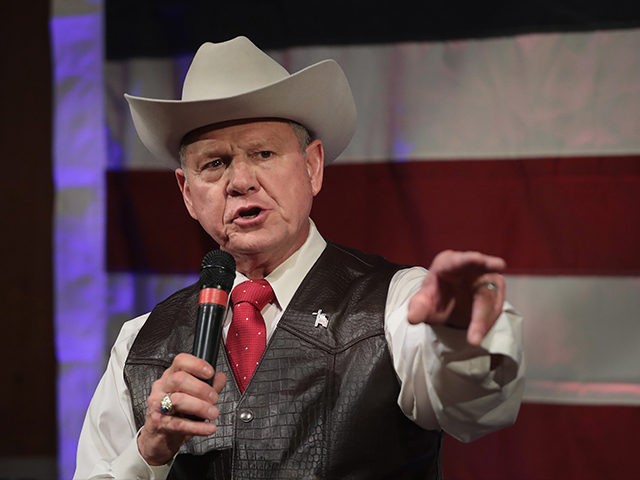

Former Alabama Chief Justice and U.S. Senate candidate Roy Moore has always enjoyed a good fight.

Born in 1947 at Gadsden, Alabama, into humble beginnings with no connections, he fought to enter one of the U.S. military’s most prestigious academies.

Moore had been inspired by the 1955 movie The Long Gray Line, about an immigrant who finds his life work at West Point.

He wrote to his congressman, then-Rep. Albert Rains (D-AL), and got a recommendation. He was confirmed by then-U.S. Rep. James Martin (R-AL). It was a competitive process, Martin said in an interview with local newspaper Montgomery Advertiser.

“I just saw in him some potential,” he told the paper. “I thought he had the ability to make the grade, and he did.”

Moore won a spot at West Point, and his father, a construction worker, borrowed $300 to pay for his son’s ticket and traveling expenses. Moore reported to West Point shortly after he graduated in high school in 1965.

West Point classmates remember him being disciplined about religion.

At West Point, Moore taught Sunday school, forgoing the one day a cadet could get a little rest or sleep, according to John Bentley, fellow classmate who entered West Point in Moore’s senior year and now a county circuit judge in Alabama.

He also credits Moore, who lived next to him, with saving his Southern accent, after some second year students (called yearlings) ordered him to get rid of it one day, he told the Advertiser.

“(Moore) walks out and shoos these yearlings off and whispers, ‘Don’t you dare lose your Southern accent,’” said Bentley. “I credit him for saving my Southern accent.”

Writer and journalist Lucian Truscott IV, another classmate who was in Moore’s class of 1965, said he remembers Moore as a “pretty intolerant guy” over his conservative religious views.

Truscott was part of a group of cadets who were pushing to end mandatory Catholic, Protestant, or Jewish religious services. He told the Advertiser that other cadets had told him to “watch out” for Moore.

“Among the classmates I talk to, there’s a very strong memory among everybody that he was a pretty intolerant guy when he was a cadet,” he said. “Very, very conservative, and intolerant of people who had different points of view than he did.”

Moore lost his father while he was at West Point, and he briefly considered dropping out and returning home to care for his younger siblings, according to al.com. Moore was the eldest of five.

Other classmates urged him to stay, including Dick Jarman of Kansas City. Jarman told al.com that it was a difficult time for cadets at West Point — every week, bodies came back to the campus for burial, and graduates knew they were headed to the battlefield.

Jarman said Moore’s faith “set him apart,” but that he never pushed his beliefs on others. Sometimes, he would pray during grueling marches through nearby mountains, and other cadets would tease him, saying, “Roy, you know you can pray from the ground.”

Jarman also said Moore was untrained in gymnastics but was committed to learn the pommel horse and eventually earned a spot on the academy’s gymnastics team.

He graduated West Point in 1969. He then served as a military police officer at Fort Benning, Georgia, and Illesheim, Germany before deploying to Vietnam in 1971 as commander of the 188th Military Police Company of the 504th Military Police Battalion.

The unit supervised a military stockade in Da Nang, Vietnam. Jarman said Moore served in an area that saw heavy fighting.

In Vietnam, his soldiers said he was a stickler for discipline, which reportedly antagonized some of whom called him “Captain America.”

Moore wrote in his autobiography that he was “shocked” at the lack of discipline in the company, and began cracking down on drug use and issuing Article 15 charges, which are nonjudicial punishments. He focused on regulation haircuts and wanted to be saluted on the field, even though that could identify him as a target for the enemy.

He was so convinced that one soldier was going to kill him that he put sandbags under the bed, to keep grenades from being rolled under it, Moore wrote in his autobiography.

He set up a boxing ring in Da Nang, to ”meet all challenges from soldiers in the battalion.”

Barrey Hall, who served under Moore, told the Associated Press in 2003, “His policies damn near got him killed in Vietnam.”

But not every one felt that way about him.

Trial lawyer Bill Staehle of Asbury Park, New Jersey, served with Moore in Vietnam from 1971 to 1972, and said he was an “altogether honorable, decent, respectable, and patriotic commander and soldier.”

They were both captains and company commanders in the 504th Military Police Battalion, stationed at the base camp called Camp Land, west of Danang, he wrote in an open letter published by Yellowhammer News.

Staehle said he got to know Moore during his first four months in-country before he was reassigned within the battalion to another location, and grew to admire him. They were both 24.

He said the experience with Moore that best summed up his integrity was one day when another officer invited him and Moore to go with him into town after duty hours for a couple of beers. He said he and Moore both wanted to hear about his experiences in Quang Tri Province north of Danang.

When they arrived at the place and went inside, it became clear it was a brothel. “The place was plush. There were other American servicemen there. Alcohol was being served. There were plenty of very attractive young women clearly eager for an intimate time,” he said.

“In less time than it took any of the women to approach us, Roy turned to me and said words to this effect, ‘We shouldn’t be here. I am leaving,’” Staehle said. The officer told them to take his jeep back to the camp, and he could get a ride later. He and Moore drove back to the camp.

“That evening, if I didn’t know it before, I knew then that with Roy Moore I was in the company of a man of great self-control, discipline, honor, and integrity. While there were other actions by Roy that reinforced my belief in him, that was the most telling,” he said.

Staele told the story in light of allegations that Moore just a few years later behaved inappropriately towards women, which he said were “obvious, politically motivated allegations.”

“What I saw, felt and knew about him in Vietnam stands in stark contrast to those allegations,” he said. “I sincerely doubt that Roy’s character had changed fundamentally and dramatically in a few short years later.”

“Roy was a soldier for whom I was willing to put my life on the line in Vietnam if the occasion ever arose. Fortunately, it did not,” he said. “I was prepared to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with him then, and I am proud to stand by Roy now.”

Moore left the Army in 1974 at the rank of captain, and would go on to attend the University of Alabama Law School, graduating in 1977.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.