So what’s Washington, DC, reading? Beyond, that is, the tribulations of the Trump administration, the controversies of the Democrats, and the always critical question that vexes “This Town”: what’s the hottest restaurant? As The Washington Post asked last month, is it possible to get a decent dinner for two in DC for less than $100?

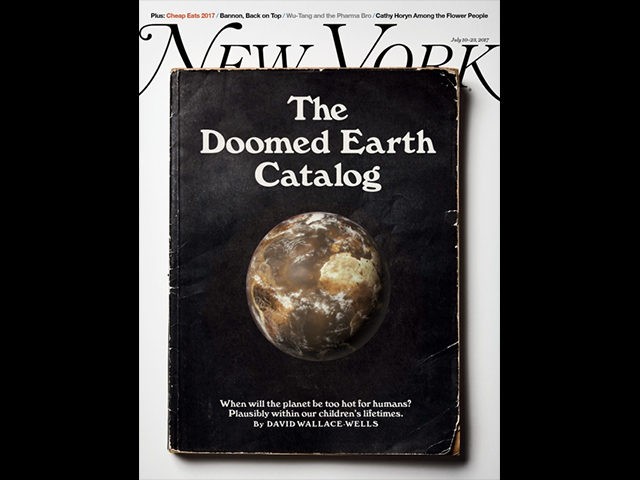

Okay, so here’s another item that’s punched through inside the Beltway: A new article on climate change—a cover story, in fact—in New York magazine is getting lots of attention. The headline was indeed a grabber: “The Uninhabitable Earth: Famine, economic collapse, a sun that cooks us: What climate change could wreak—sooner than you think.”

The piece, by one David Wallace-Wells, has been touted in Politico’s July 10 edition of “Playbook” as a key “Afternoon Read.” And then the equally Beltway-buzzy Mike Allen—himself formerly of Politico and “Playbook”—touted it even harder in his Axios AM report that blared, “If you read only 1 thing: ‘Doomsday.’”

Admittedly, such hyping doesn’t guarantee that the article will play in Peoria, but it’s a safe bet that many leading Democrats, and their Green allies, will be devouring “The Uninhabitable Earth.” Indeed, lest anyone think that some headline-writer oversold the story, here are the actual first words:

It is, I promise, worse than you think. If your anxiety about global warming is dominated by fears of sea-level rise, you are barely scratching the surface of what terrors are possible.

The author understands that his core readership is likely to have kept up with the daily—or is it hourly?—updates from The New York Times on the presumed horrors of climate change. Still, he continues, there’s more to fearful of: “No matter how well-informed you are, you are surely not alarmed enough.”

To further pound the point home, the article is festooned with imaginative graphics of future human “fossils,” all meant to illustrate the deadly end that CO2 supposedly foretells for us as a species.

Some have accused Wallace-Wells of overwriting his piece, and in fact, there’s been plenty of pushback, including from “Playbook,” which fair-and-balanced-ly cited a Green critic of the article. Indeed, some more moderate Greens have taken issue with the lurid tone of the piece—although, of course, such controversy might only increase its notoriety. As they say, Just spell the name right.

In fact, there’s already a thriving market for climate-change doom-and-gloom. Indeed, there’s a rapidly expanding genre known as “climate fiction,” or “cli-fi,” which includes such books as Year of the Flood, The Drowned Cities, and The Water Knife; there’s even a book on how to write your own book: Saving the World One Word at a Time: Writing Cli-Fi. And of course, there are plenty of movies with cli-fi plots or themes, including The Day After Tomorrow, Interstellar, and Snowpiercer. And coming soon: Gerard Butler in Geostorm.

It might well be the case, of course, that there’s more eagerness, in Manhattan and Hollywood, to supply these works than there is eagerness among ordinary audiences to consume them. Yet still, the cumulative weight of all this Green-themed content is having some impact—as the polls suggest.

Yet even if cli-fi can be dismissed as a case of the elite attempting to force-feed its worldview onto the non-elite, we still might be curious to ask: Where did this high-end end-is-nigh impulse come from in the first place? Why are so many in the upper crust so eager to embrace such pessimism?

One answer, of course, is that the idea of eschaton—the consideration of the world’s end—has always been with us; it is simply always finding new fans and taking on new forms. Wikipedia provides a handy, if hardly complete, list of doomsday prophecies from the past, as well as plenty more about the near future.

Moreover, in 2011, The New Scientist magazine looked at the question of “Why do we like reading about our own destruction?” It quoted Lorenzo DiTommaso, a professor of religion at Concordia University in Montreal, describing doomsayers across history: “They tend to be quite intelligent compared with the general population but they are looking for answers for how life is the way it is.”

Of course, some might dispute that these apocalypse-now-ers are, in fact, “quite intelligent,” but it’s impossible to deny that today at least, they tend to be well-educated and well-off.

We can further observe that for the elites, special knowledge of a certain type is a kind of status symbol. That is, it’s empowering to think that one knows things, and sees things, that mere proles and other lesser mortals aren’t smart enough to know and see. So if the elites are as anointed as they think they are, then of course they have a vision that gazes farther into the future than everyone else. By this reckoning, a serious concern about climate change is what sociologists call a “signifier”—that is, an indicator of exalted status.

Adding that doomsayers have a distinct and articulated worldview, DiTommaso continued:

Within its limitations, apocalypticism is very rational. It’s a worldview that explains time, space, and human existence. It’s not science—it’s not universal or repeatable—but it does explain things.

The professor also said that for the world-enders, a vision of doom “provides a very powerful way of understanding the world and all its problems.”

We might linger over those words, “a very powerful way of understanding the world.” We can further observe, in the hands of the motivated, that an argument doesn’t have to be true; it merely has to be useful.

Moreover, we can see that such mind-tools suggest that doomsayers will find comfort in political activism, as well as religious belief—especially an active belief in Green religion.

And since we’re speaking of professors and their new forms of faith, we might recall the famous case of Stanford University’s Paul Ehrlich. Back in 1968, Ehrlich published The Population Bomb, declaring, “The battle to feed all of humanity is over”—as in, humanity has lost. Indeed, he predicted that “hundreds of millions” would starve to death in the 1970s, including 65 million Americans.

Finally, he concluded, “Sometime in the next 15 years, the end will come”—that is, “an utter breakdown of the capacity of the planet to support humanity.” By now, the chronologically inclined reader will have calculated that Ehrlich’s prediction of global degringolade was set to occur in 1983. (In that year’s World Series, the Orioles beat the Phillies in five; in other words, despite Ehrlich’s prophecy, human affairs carried on.)

Yet revealingly, even though The Population Bomb was a bomb in terms of accuracy, it remained in print for decades; we can only conclude that for some, the veracity of a prediction is less important than its utility. That is, some people actively want to believe the worst, truth be damned.

And of course, an active belief in anything is the seedbed of political activity. And the Greens have certainly been active. As this author has noted in the past, the 2016 Democratic Party platform proved to be far more attentive to the issue of climate change than to the well-being of middle-income workers. (That might help explain why Hillary Clinton did so poorly among those folks last year.)

Of course, since then, the Greens haven’t gotten any weaker; if anything, they are stronger inside the Democratic Party. And thus we come back to Wallace-Wells’ piece, the one that seems to tell us that we’re all doomed—the sad scenario that brings smiles to the faces of so many Greens.

Yet interestingly, foreordained doom isn’t quite what the author foresees. Indeed, despite the despairing tone of the piece, at the end, after 7,000 dire words, the piece’s conclusion is rather hopeful; the author volunteers that despite all the climate-darkness, there’s a ray of hope.

Happily, that ray of hope isn’t just some figment of imagination, but rather, a solid beacon of historical precedent—the knowledge that in the past, technological progress has saved us, and it can do so again. As the author puts it, to reach the carbon dioxide goals set by the Greens will take some doing, but we can do it:

By 2050, carbon emissions from energy and industry . . . will have to fall by half each decade; emissions from land use (deforestation, cow farts, etc.) will have to zero out; and we will need to have invented technologies to extract, annually, twice as much carbon from the atmosphere as the entire planet’s plants now do. Nevertheless, by and large, the scientists have an enormous confidence in the ingenuity of humans—a confidence perhaps bolstered by their appreciation for climate change, which is, after all, a human invention, too.

In other words, if we have invented our way into a problem, we can invent ourselves out of it.

Ah yes, human inventiveness: It’s been changing our world since cave-men stumbled into the sparking of that first fire. And more recently, since the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions of the 17th and 18th century, inventiveness has changed our world a thousand times more. And so, Wallace-Wells asks, why shouldn’t human invention continue into the future? As he himself writes, if we can put a man on the moon, we can de-carbonize the atmosphere.

To be sure, some on the right will argue that we shouldn’t bother worrying about CO2, because climate change is a mirage, or even a hoax. And that might be the case—or it might not.

Yet either way, being mindful of global political realities, it can’t hurt for all of us to prudently explore ways of improving our scientific understanding of carbon capture.

The upside of such an understanding is the greater likelihood that we will be able to continue burning the hundreds of trillions of dollars of fossil fuels—oil, gas, and coal—that is yet to be found in the US, as well as saving the tens of millions of well-paying American jobs in the fossil-fuel industry.

With the economic well-being of red-state America—and of all America—in mind, this author has argued for such a carbon-capture strategy in the past, including here, here, and here.

Okay, leaving aside eschaton, ideology, and technology, what about the raw politics of the carbon-capture issue? What do the two parties think of it? Right now, carbon-capture has little salience, even if it is a multi-billion dollar effort.

Yet looking ahead, we can assume that Republicans, who mostly represent the fossil fuel states, from Texas to Kentucky to North Dakota to Alaska, will be on board with anything that lets them and their voters continue to drill, baby, drill.

Alright, so now what of the Democrats? Although once the “oil patch” was solidly Democratic, these days, newer Democrats have been hostile to the extractive industries; they are now the party of high-tech “post-industrial” classes, as well as public-sector dependents—and neither are much interested in old-line energy jobs.

Yet still, as the reality that they lost the 2016 election—as well as the four contested special elections in 2017—sinks in to the Democrats, they might find that they, too, will be well-served by a non-greenhouse gas-producing energy solution. After all, they have to do something to get back the votes of working-class whites—and they know it.

So there’s at least the chance of a meeting of the two parties’ minds, based on that classic American goal: More.

To be sure, we shouldn’t minimize the challenges ahead for a carbon-capture strategy, but the upside, in terms of economic gains and political cooperation, makes it a worthy undertaking.

Yes, it’s a bit ironic: That ultra-gloomy New York magazine article ultimately comes down on the side of hope, including hope for folks in the Heartland, whose livelihoods and futures depend on robust energy production.

Indeed, one can even look at the piece and see within it the prospects of a blue-state/red-state reconciliation, of the kind that our polarized and divided nation sorely needs.

So who knows: Maybe one day it will be said that the challenge of climate change, when twinned with the imperative of economic growth, served to actually bring Americans together, joined in a new era of prosperity.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.