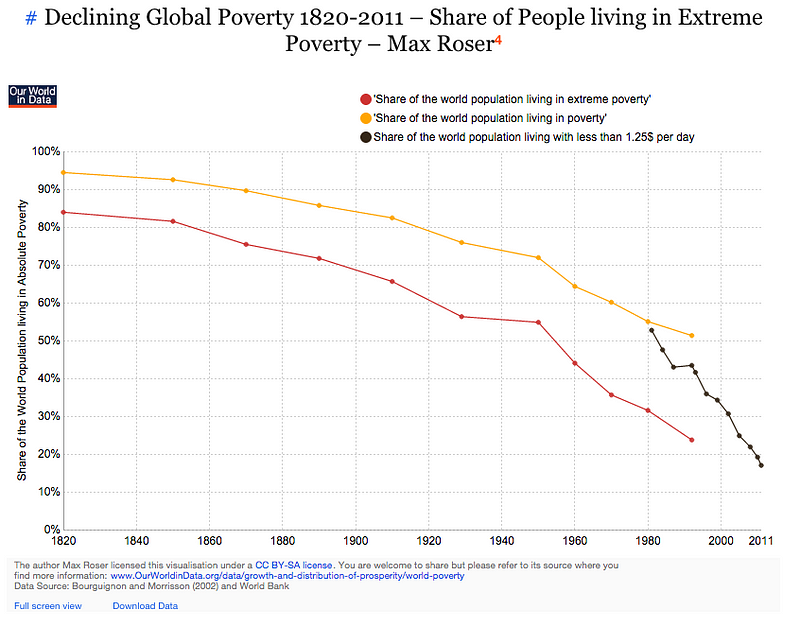

Ourworldindata.com / Max Roser

Despite lingering gloom from the economic recession, life is getting much better for the most distressed people all over the world. Since the 1980s, the share of people living on less than $1.25 day has plummeted from 53% to just 17% in 2011. Globally, those at the bottom of the economic ladder is “falling faster than ever,” according to Oxford economics Fellow, Max Roser.

Indeed, the World Bank is so elated by the trend that it believes, for the first time in human history, poverty can be completely eliminated by 2030.

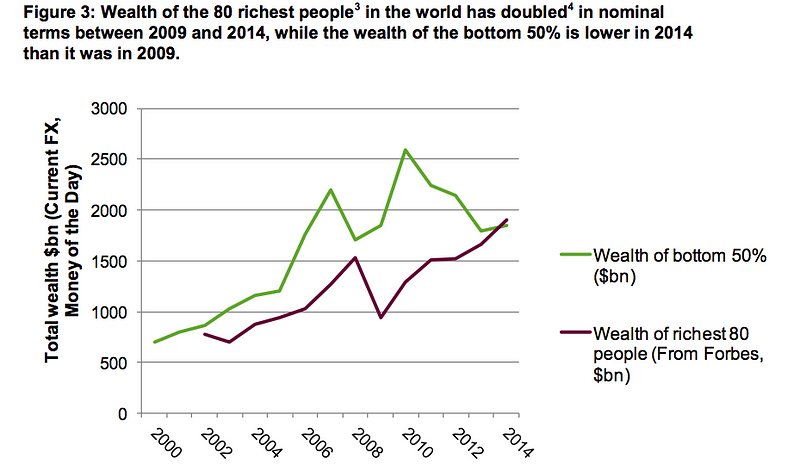

Yet, at the same time, the global rich-poor class gap is skyrocketing; as of 2014, the richest 80 people in the world now control more wealth than the bottom 50% combined [PDF].

Source: Oxfam

So, why is poverty decreasing while inequality is increasing?

Lund University economist, Andreas Bergh, has a contentious, if fascinating, theory: greater inequality means a greater portion of the population exists at the lowest income, making it cheaper to provide goods to a larger share of lower-income consumers. The more people need cheap products, the more incentive companies have to streamline non-luxury versions of food, education, and other goods. In other words, lower-income people scale.

In this way, rather than having an even distribution of income over many economic classes (e.g. low, low-middle, middle, upper-middle, and upper), an economy with only a few classes allows companies to focus on making products for greater portion of similar customers.

In his paper, “When More Poor Means Less Poverty,” Bergh finds that as inequality increases around the world, the cheaper rice and Big Macs become.

His explanation is worth quoting in full:

On average, a 10 point increase in the Gini coefficient (corresponding to shifting from the level of inequality in Latvia to Kenya) decreases the time required to buy a kilo of rice by 7 minutes (compared to the 2007 global average of 22 minutes). Similarly a corresponding inequality increase would on average decrease the time required for a Big Mac by 16 minutes (compared to the 2007 global average of 37 minutes).

The Android Class

Think of the difference between the global poor and rich as the difference between the iOS and Android operating systems. Apple designed a phone that only a relatively small portion of the world can afford. But the iPhone opened up an entirely new mobile market, allowing Google to create its free mobile operating system for the rest of the non-iPhone-toting world. Android especially thrives in countries with a broad lower-income base.

The more people need a cheap operating system, the more demand Google and its hardware partners have in making smartphones accessible. In other words, the co-existence of an influential rich class and large lower-income class can have economic benefits.

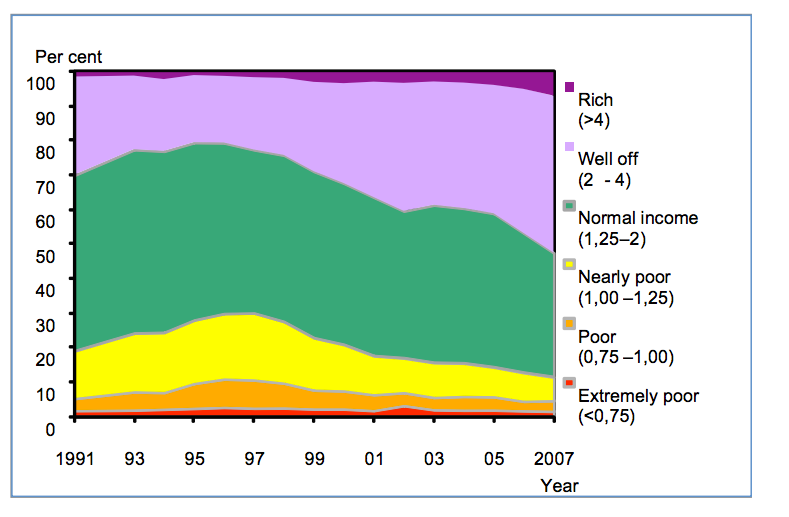

Indeed, this could be one reason why even in Sweden, the former poster-child for financial equality, poverty is decreasing while the rich are getting richer [PDF].

Now, careful readers will note that an inverse relationship between poverty and equality is not an iron law of economics. It’s often the opposite. In many nations and U.S. states, increasing inequality makes life worse for the poor. The rich get richer, and nothing trickles down. Moreover, in nations where poverty is decreasing, it is often because welfare services have expanded. The market itself is not eliminating poverty.

But inequality and a shrinking middle class is not inherently bad for the poor. This is not to say we should cheer inequality or that the middle class should donate their money to the rich in the interests of alleviating poverty.

There is a nuanced relationship between income distribution and extreme poverty. We must be careful how we model welfare systems and taxes so that we maintain the productive parts of inequality while reducing its ill effects.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.