Martin Greenfield has been hailed “America’s greatest living tailor” and the “most interesting man in the world.” A Holocaust survivor, Mr. Greenfield makes suits for the world’s most powerful and influential men, including Hollywood stars, presidents from both political parties, and pro athletes.

His new book, Measure of Man: From Auschwitz Survivor to Presidents’ Tailor, launches today.

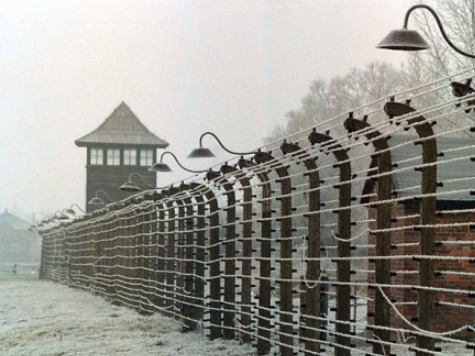

In the excerpt below, Mr. Greenfield recounts the Nazi brutality he endured and witnessed inside Auschwitz.

Day and night the ovens burned. The smoke spewed up from the soaring brick chimney and belched the vaporous remnants of corpses into the air. At night you could see the flames spitting against the blackened sky. Still, no one in the camps talked to me about the crematoria. Whether that was because I was just a boy or because I no longer had a father by my side to speak piercing truths to me, I do not know. But I could smell that something was horribly wrong.

After morning roll call, we were given something approximating black coffee. To be sick or weak was dangerous, so no matter how rancid the gruel or vile the smell, I forced myself to eat. The afternoon slop was usually some sort of soup that frequently had human hair, trash, or dead insects floating in it. Sundown brought black bread mixed with sawdust. Soup made you skinny. Bread made strength. So I ate as much bread as I could scavenge and always tried to cover my wounds with my clothes.

My labor assignment in the laundry lasted several days before I was moved to the sorting room, which housed the confiscated wares of newly arrived prisoners. The space was filled with fifty or so prisoners combing and sifting mountains of clothes, shoes, and other possessions. Sometimes a prisoner stumbled upon a hidden morsel of food folded inside a bag or tucked inside a coat pocket. Prisoners caught trying to sneak a bite were promptly whipped by a kapo, who often smuggled the food or ate it himself.

Between the rummaging and sorting I peeked over and around piles every chance I got in the hopes of spotting a family member. That’s all I wanted: one glimpse, a single fleeting confirmation they were still alive. But it never came. Looking back now I realize that false, cruel wish, like an invisible ladder whose rungs materialized based on hope, compelled me to reach for survival.

The weeks passed and the piles got smaller and smaller until transports of new prisoners slowed to a trickle. The Nazis reassigned me to the bricklaying teams. Allied bombs were busting up brick buildings everywhere, so our services were in high demand. I knew nothing about masonry. A prisoner who served as a team leader stuck a trowel in my one hand and a mortar bucket in the other before walking me to a block of bricks. There I learned the finer points of bricklaying before being put to work.

The work was hard and the days were long, and my wire-thin teenage frame did its best to keep up with the older, stronger men. For some reason, slathering and smoothing the mortar across the faces of the bricks made my thoughts float to Pavlovo and brought back scenes of Grandma Geitel icing freshly baked cakes. Before long I had perfected my ability to detach my mind from my physical form, and my body sped up as my thoughts slowed down.

Even so, no matter how hard we worked, our captors would slay prisoners without provocation.

Killings were frequent and random. One day a boy from my block and I were tasked with building a brick wall. We started just after morning line up. By late afternoon we had completed a good stretch of the wall and felt a certain pride in our accomplishment. We stacked the bricks higher and higher until it stood some five or six feet tall. We talked while working to unclench our minds. A single gunshot rang out, but I didn’t think much of it. The crack of rifle fire and the spraying of machineguns were common, so I kept stacking and talking. I asked the boy a question and got no reply.

I asked again.

Silence.

I swiveled my head in his direction. Several yards away, the boy lay motionless, facedown in the dirt inside an expanding pool of blood. I later learned a Nazi had used the boy for target practice.

At home in Pavlovo—and in most civilizations—a clear moral order structured our daily lives. Hard work, justice, fairness, integrity—these virtues produced predictable fruits. But not in the concentration camps. The Germans killed for any reason or none at all. It was futile to try to discern their logic, because there was none. If a Nazi was angry, he might kill you. If a Nazi was happy, he might kill you. It made no difference.

The dehumanizing randomness of the murders suffocated my sense of hope, just as Hitler and his henchmen had intended. What appeared random was, in fact, not random at all. It was a systematic psychological lynching, a strangling of the human heart’s need to believe in the rewards of goodness, a snapping of the moral hinge on which humanity swings. Soon, and much to my shame, I became anesthetized to death, numb to depravity. Some primal survival switch inside me had been temporarily flicked on that allowed me to submerge the emotions generated by the evil scorching my eyes.

I witnessed dozens of shootings and helped carry scores of corpses. Sometimes a dead body would be intact and appear to be sleeping. Other times a bullet would rip through a prisoner spilling out organs. Or shatter a skull, exposing chunks of brain. But as the days passed, no matter its condition, a body soon became just a body, a sallow, bloodless, gangling object that must be lugged, heaved atop a pile, or dropped in a hole.

At fifteen, I had become an undertaker.

Martin Greenfield is the author of the new book, Measure of a Man: From Auschwitz Survivor to Presidents’ Tailor.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.