Sometimes the education establishment in Britain appears to be a parody of itself. This morning, it was reported that the OCR exam board, despite clear calls for a return to rigour in our examination system, are developing an English Literature and Language A-Level where students study Caitlin Moran’s Twitter feed, a Newsnight interview with Dizzee Rascal, and Russell Brand’s testimony on drug use to a parliamentary committee.

Aside from the tendentious nature of these choices (would, I wonder, Peter Hitchens’ view on drug use ever make it into an exam?), we have to ask whether studying such texts is a valuable use of pupil time. There is nothing new about such dumbing down. A stroll through the recent years of AQA’s English Language GCSE shows exam papers based on news stories about Tinie Tempah, Johnny Depp, Gordon Ramsay and Jamie Oliver.

“What was Jamie Oliver’s reaction to the research about his school dinners?” reads one question. “List four thing that you learn about Tinie Tempah from the article” reads another.

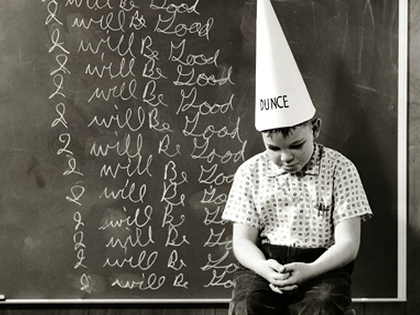

As I have detailed in my book Progressively Worse (Civitas), these curriculums are the product of a movement that took off in British schools during the 1960s and was called ‘Progressive Education’. A basic tenet of progressive education is that school curriculums should grow out of the existing interests of the child, and be made relevant to their own life experiences. A 1973 article from the influential journal New Society observed that inner-city children are interested in television, football pools, writing on walls, taking apart motor bikes and ‘dolling up’ each other’s hair. It asked, “why isn’t the education there?”

Today, the answer in many schools would be “it is”. When I became a history teacher three years ago, I had to teach a history GCSE which was designed in the 1970s to be ‘relevant’ to pupils’ interests. One unit was a study of the American West: as any trendy 1970s educator knows, kids love cowboys and Indians. It was an embarrassment of a course: boring, irrelevant and an insult to the intelligence of my pupils.

Teachers today will talk at length about the need to make school work ‘accessible’, but this is merely a euphemism for dumbing down. There is a fundamental problem with work that is ‘accessible’: instead of challenging pupils to reach outside of their existing interests, ‘accessible’ work panders to them, and pupils’ ability to transcend their intellectual horizons disappears.

School should aim to do more than simply duplicate the cultural exposure children receive in their daily life. School should raise pupils above the ordinary, and interest them in subject matter they would not otherwise think to read. The poet laureate Ted Hughes was a great supporter of memorising canonical literature in schools. He wrote: “In English students are at sea, awash in the rubbish and incoherence of the jabber in the sound-waves”, but argued if they know by heart the work of great poets, they are given “a great sheet anchor in the maelstrom of linguistic turbulence.”

You may think Hughes’ view is all good and sensible. But try expressing it in one of today’s state schools. You will risk being called a bigot and an elitist, with no respect for the interests of the child. A twin movement to progressive education is cultural relativism. All cultural products are of equal value, it is claimed. But this is clearly rubbish. Shakespeare, Dickens and the Romantic Poets have endured for centuries in a way that Russell Brands’ Booky Wook will not. Why should we teach contemporary texts of unproven literary significance, when there are works which have endured, and shaped the very way we speak today?

The essential question is one of opportunity cost. Every moment in school spent tarrying through ephemeral, disposable ‘literature’ such as Twitter feeds and news interviews is time that could be spent enriching pupils’ knowledge of the best that has been thought and said. The current education secretary, Michael Gove, understands this, and that is why he has been doing his damdest to give stronger stipulations governing what exam boards are allowed to examine. However, the new English and Maths GCSEs are only set to be taught from September 2015. History, geography and science will be a year later.

Though I am not a party animal, my great fear about Gove not being in place this time next year is that Labour will not have the nerve to stand up to the vested interests of the education establishment. The direction of reform will be reversed, and children will be back to reading trash in the place of great texts.

Robert Peal is an Education Research Fellow at CIVITAS. He tweets at @GoodbyeMrHunter

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.