Hafez, the 11-year old son of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, reportedly posted a blistering taunt of President Obama on Facebook. Despite being deliberately antagonistic, his strategic analysis of the situation is remarkably cogent and pointed (suggesting an 11-year old might not have actually written it). What hasn’t received much attention is an important analogy he makes between an American war with Syria and Israel’s 2006 Summer War against Hezbollah, which Israel lost.

Hafez is right to make this comparison. Hezbollah is viewed by much of the world as having defeated Israel simply by surviving Israel’s bombardment and limited ground offensive in Lebanon, thus bringing into question the overall legitimacy of the operation itself.

Israel used the military targeting philosophy of Effects Based Operations (EBO), which taught that striking measurable targets could accomplish strategic military victory over the minds of the enemy leadership and military. EBO was the doctrine we were employing in own war efforts at the time, and Israel had learned it from us.

Hezbollah presented a difficult problem for Israel; it had come to control the Lebanese state’s infrastructure over a long period of time, such that even though it did not formally own the state of Lebanon, it completely controlled it. Israel believed, and stated, that if it bombed Lebanon it would force the Lebanese to expel Hezbollah.

Quite the opposite happened. Israel destroyed a significant amount of Lebanese infrastructure without corresponding damage to Hezbollah. Hezbollah had planned ahead. They knew that Israel was using America’s EBO military doctrine, so they adopted the strategy of swarming, which Red Team commander Marine Gen. Paul Van Riper had employed to defeat the American military in the massive 2002 Millennium Challenge war game, the most expensive war game in U.S. history up until that time. Van Riper was so effective that he was slapped with extra rules to prevent his success as the war game cycle progressed.

Hezbollah used the same strategy by hiding in tunnels during the preparatory and supporting Israeli strikes and emerging in swarms around invading Israeli forces, mitigating their decisive potential, and then retreating to safety.

Nevertheless, in 2006, Israel was powerless to impose its rules of warfare on Hezbollah. Israel’s model of victory was expelling Hezbollah, but Hezbollah’s model of victory was simply surviving; their victory they achieved to Israel’s shame.

In 2013, America risks being put in Israel’s pre-conflict position, except for one great difference. Assad is the Syrian state. He is not a shadowy nation in a host state, like Hezbollah in Lebanon. However, like the Summer War of 2006, America is in no position to accomplish the objective of stopping Assad’s use of chemical weapons on all three levels of military campaign planning: the (1) Tactical, (2) Operational, and (3) Strategic levels.

From small to large — Tactical, Operational, then Strategic:

1. On the Tactical level, targeting chemical weapons storage facilities, even with smart munitions, is incredibly dicey. Tactically, for the mission to be a success, the chemical weapons must be destroyed without releasing the weaponized gas. This represents a most difficult “weaponeering” problem.

If the chemical weapons storage facility is destroyed, it’s likely the destruction of the weapons will release the gas, a very bad situation. If the weapons are not destroyed, but American troops are not deployed to contain the site, it’s quite possible these weapons could be taken by enemies of Assad, who are hardly proven allies of the United States. Because of the truth of the military adage, “No plan survives first contact,” we must ask, “What can go wrong striking chemical weapons?” A lot.

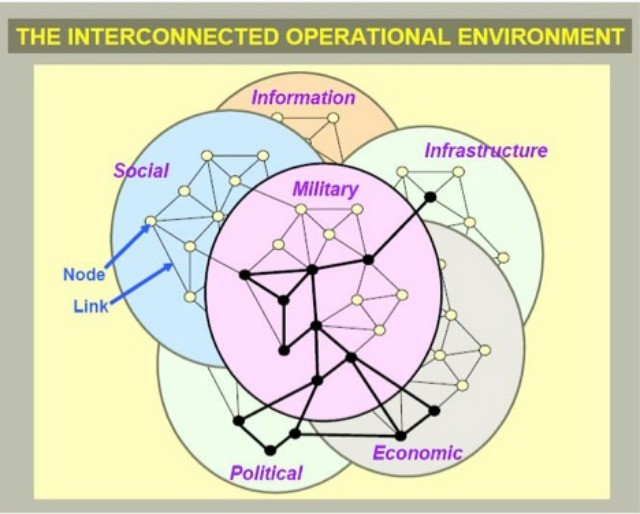

2. On the Operational level, crippling Syria’s ability to deploy chemical weapons is a complex problem involving the targeting of multiple systems. To plan operations like this, the U.S. military often uses a systems of systems analysis construct called PMESII (standing for Political, Military, Economic, Social, Infrastructure, and Information–depicted in the image below), which has many flaws.

But let’s suppose that military planners use the PMESII to target the intersections of political, military, economic, social, infrastructure, and information systems that only enable the storage and delivery of Sarin gas. A moment’s reflection on how truly complex those systems are should make evident that there is no way smart munitions, with no boots on the ground, will stop the deployment of Sarin gas in Syria. Even planning such a limited mission is a fool’s errand, and risks both regional escalation and “mission creep” in time and scope.

3. On the Strategic level, all Assad needs to do to win the information war is to look like the strong man by surviving and remaining in power. The American media may be able to sew the contradictory pieces of Obama’s foreign policy into a heroic Frankenstein here at home, but the world will not stitch the informational tapestry so kindly. Obama’s actions will create a narrative history that will make a hero of Assad, the way Israel helped make a hero of Hezbollah’s Nasrallah in 2006.

Also on the Strategic level, America faces imperial financial vulnerabilities due to the way Congress and the Federal Reserve have dealt with the Financial Crisis, the Bailout of Wall Street, and the subsequent measures the Federal Reserve took to heal the big banks and keep the U.S. bond market on life-support. Because we did not honestly liquidate debt and instead have printed money to artificially suppress bond interest rates, we are in no place to finance another big war. Wars are often won or lost on strategic financing.

One might argue that Obama has said he will only make a “limited” strike. Yet, in military terms, a limited strike is one that has a specific limited objective, with a specified force that will accomplish that limited objective. Because Obama has not specified an objective, the term “limited” actually means the opposite. Without this specificity, a campaign is bureaucratically unlimited because its objectives are not military but political. For example, contrast our extended presence in Afghanistan with our original intent.

But what if Obama realizes these difficulties and commits America to a full-tilt campaign to topple Assad and his regime? Then we face the likely scenario of “catastrophic success,” in which we win but must deal with the aftermath. Given our history in Iraq and Afghanistan, and our Federal government’s current international reputation as a massive global spy machine/empire that consolidates its power in defiance of its primary legal authority, the U.S. Constitution, catastrophic success would likely further sully our international legitimacy and potentially put the United States into a dangerous international position in the long-term.

Catastrophic success would demand that America take over Syria for the foreseeable future. Such a move could give China and Russia reason to form a credible alliance with the support of other national partners.

Which leaves Obama’s moral argument: we must act because international moral norms (whatever their current state might be) and relevant international laws forbid the use of chemical weapons. He has a point.

While it’s absolutely true that Assad is a butcher who has murdered many thousands of his people, some through the use of forbidden methods, we must still ask: do we need to take military action to condemn Assad? Do we have a moral responsibility to right all wrongs militarily beyond our borders? There is a vast difference between condemning an action and taking military action to stop it.

Our government, under the mantle of “global superpower,” has an obligation to stop international evil. However, that obligation cannot extend beyond one’s ability to act, and to attempt to do so is counterproductive in the long run. If a Syrian war is realistically viewed as unwinnable at all three levels of war in advance of the conflict, and a Syrian war would economically and militarily compromise our national security in the long-term, it becomes immoral for our government to enter into such a conflict. The United States government’s first and foremost role is to protect it’s citizens.

Unless the President can overcome these objections and define a winnable, specific limited objective, he has no responsibility taking America into war.

So Mr. President, what exactly are we trying to accomplish?

Dr. Michael Collender did his doctoral research in how metaphor andnarrative model complex systems in neuroscience and economics. He hasbeen a Visiting Fellow in the Philosophy Institute at the CatholicUniversity of Leuven, Belgium, and has researched and lectured at theJoint Forces Staff College in Norfolk, VA. For more resources subscribeat SolveWickedProblems.com and follow @mcollender.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.