Paul Volcker may be right when he said on Monday at the New York Athletic Club, regarding the Federal Reserve’s latest bond-buying program, that “…it’s not going to have any effect on inflation in the short run…The basic situation is not an inflationary situation.” Inflation may not be with us at the moment, and Mr. Volcker did not define “short term.” However, with the federal government generating an annual fiscal gap of at least 8%, which, in the absence of Congress acting responsibly, is being filled by the Fed’s printing money, it seems to me that it is a question of when, not if, inflation returns.

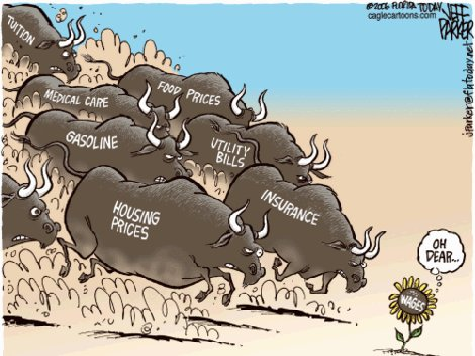

There are many ways to destroy wealth, but inflation can do so with insidious ease. It is a tax that creeps up unannounced and surreptitiously makes itself felt. What is important to middle class and poorer people is not what government claims inflation to be, but what it actually costs to buy a loaf of bread, a dozen eggs and a pound of chopped beef, and what it costs to fill the car with gas and to heat one’s home. The official CPI number (1.7% year-over-year as of August) appears low, which would not be surprising, as a low CPI saves the government billions of dollars in annual increases in programs like Social Security that must adjust for inflation. Belying the reported inflation number, the currency component of M1 has risen 6.3% in the first nine months of this year. Also, we know that oil prices are 7.3% higher than a year ago, and that food commodity prices have risen even faster. Corn is up 13%, Soybeans are higher by 28.3% and wheat costs 21.3% more than it did a year ago.

Bucking the trend has been a 29.5% decline in the price of natural gas, which has produced modestly lower electricity costs over the past twelve months – a modest blessing in an otherwise sinister scenario. Adding pressure on consumers, the U.S. Census Bureau reports that median household income is 1.5% lower than it was a year earlier – marking the fourth such decline in as many years. And, according to the Pew Research Center, the number of Americans identifying themselves as “lower class” today is 32%, compared to 25% in 2008. With food and energy prices higher and incomes lower, those results should come as no surprise. But it is the rise in federal debt that poses the biggest problem for future inflation.

In his most recent “Investment Outlook,” William Gross of PIMCO writes of the potential debt peril. He prefaces his remarks: “Armageddon is not around the corner. I don’t believe in the imminent demise of the U.S. economy and its financial markets.” But,” he adds, “I’m afraid for them.” He then writes of the difference between the annual deficit and the fiscal gap. The former is the reported number, but excludes future estimated entitlements such as Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, none of which show up in current expenditures, but are nevertheless obligations. The latter includes them. Unless we begin to close both gaps, debt to GDP will continue to rise. The Fed will have to continue to print money to fund operations, with the inevitable consequence of ultimately debasing the currency and exasperating inflation. Quoting the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Bank for International Settlement (BIS), Mr. Gross concludes that the U.S. balance sheet “is in flames and that its fire department is apparently asleep at the station house.”

My fear of future inflation could well be overstated, or certainly be premature. Certainly the bond markets don’t seem overly concerned. With the Fed’s announcement of QE4 on September 17, the spread between Ten-Year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities and the Ten-Year Treasury Note widened to 273 basis points, its highest level since May 2006. But, with Mr. Volcker’s comments on Monday, the spread narrowed to 242 basis points on Tuesday. It is, however, an index that bears watching.

Advances in farming technologies – irrigation systems, equipment, fertilization and seeds – have increased yields per acre, not only in developed countries, but in emerging ones. The consequence has been lower or only modestly higher food prices over several decades. Similarly, apparel prices have come down during the past few decades, as manufacturers, taking advantage of lower labor costs, moved facilities to developing countries, mostly in Asia. During much of the 1980s and all of the 1990s, commodity prices trended lower, providing special dividends for consumers, until moving sharply higher over the past ten years. Technology has enhanced productivity for most all manufacturing facilities. As commodity prices rallied over the past decade, governments kept interest costs low, helping to offset costs for manufacturers, farmers, assemblers, distributors, retailers and consumers, who also benefitted from easy credit and low mortgage rates. The bottom line has been favorable for food and apparel over a long period of time. Perhaps these trends will persist, but it does seem possible that much of the low-hanging fruit has been plucked.

Because the Fed is determined to keep long rates low, the Treasury has been unable to issue longer-dated paper (like 30-Year or 100-Year bonds or even perpetual bonds, like the British Consols issued during the Napoleonic Wars.) Common sense suggests the sagacity of extending maturities with interest rates as low as they are. However, and in contradiction of common sense, the last five years of the Bush Administration saw Treasury maturities decline from roughly six years to four years by 2008. They have since risen to about five years, but the United States still has one of the lowest maturity schedules of any country in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Even the debt of Greece, according to Seeking Alpha, has an average maturity of eight years. At a time of very low interest rates, shortened maturities make sense for an investor, but not for an issuer.

Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke seems convinced that once unemployment reaches 7%, or whatever level he deems acceptable, brakes will be applied and the helicoptering of dollars will cease. We will see. Federal debt, at just over $16 trillion currently, exceeds 100% of GDP, which is estimated to be $15.8 trillion by the end of the year. In the past four years, federal debt increased by $6 trillion, while we added $1.2 trillion to the nation’s gross domestic product. It is not a given that the Treasury will use depreciated dollars to pay off its debt, but it is certainly not inconceivable.

Mr. Gross ends his note with a warning of what will happen if the existing and “fiscal” gaps do not close. He writes of how for forty years the global financial system “has depended on the U.S. economy as the world’s consummate consumer and the dollar as the global medium of exchange.” If the gaps are not closed “even ever so gradually,” then rating agencies and the rebirth of bond vigilantes may “force a resolution that ends in tears.” As the headline in The Onion for the story by Alana “Honey Boo Boo” Thompson reads, “You do, of course, realize that this is going to end very, very badly.”

________________________

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.